Data Transparency: According to the latest Scottish Parliament Business Bulletin, the next meeting of the Rural Economy and Connectivity Committee will receive an update to their Salmon Farming in Scotland inquiry of 2018. At the time, the committee said that ‘the status quo is not an option’. However, this statement arose from a misunderstanding of the industry because for salmon farmers, the status quo has never been an option. The industry has always worked to ensure the best practice available. The industry in 2020 is very different from the one in 2010 and that was better than that of 2000 and so on right back to the 1980s. Clearly, if the industry was starting out now, it would be a very different proposition to the days of small wooden pens located in the most sheltered parts of the coast. We know so much more than we did then, and this quest continues.

I would imagine that in the short time since the inquiry, the industry will be able to demonstrate significant improvements in what they do and how they present themselves despite the efforts of a vocal minority who seem to believe that a picture of one damaged fish is sufficient proof to warrant the closure of the whole industry. Salmon & Trout Conservation have been particularly busy trying to influence the committee through the media. Of course, it is worth remembering that the inquiries were initiated as a result of a (flawed) petition from S&TC claiming that the salmon farming industry was responsible for the decline of wild salmon and sea trout stocks and therefore needed to be subjected to increased regulation.

Regular readers of reLAKSation know that I vehemently dispute these claims but sadly S&TC are not prepared to discuss the facts. They prefer to tout their message to those who are not sufficiently knowledgeable to dispute the data.

Which brings me to the data, for whilst the salmon farming industry has been making more data available to the critics, access to the wild fish data has become increasingly restricted. How can the salmon farming industry understand whether they are having an impact on wild fish or not when there is increasingly less and less information about the status of wild fish available in the public domain? I’ll come back to this later, but first want to consider an article that appeared in Intrafish on November 5th.

The anglers’ representatives in Norway have declared that 2020 has been some of the best salmon fishing in five years. Based on the catch data from selected rivers, Norske Lakseelver estimate that 129,415 salmon were caught by anglers in Norwegian rivers. Of these 25% were released meaning that just 100,000 salmon were caught and killed.

They say that this is the best year since 2015 when 133,141 fish were caught. 2020 should also prove to be about 10% better than the average catch between 2000 and 2019.

The 20 page glossy pdf detailing the catches from across Norway can be downloaded from https://lakseelver.no/sites/default/files/Norske_Lakseelver_laksesesongen_2020.pdf This has taken Norske Lakseelver about two months to compile including the time needed to produce a well-polished publication.

According to Norske Lakseelver, the official Norwegian catch statistics will be published in January.

Fishing for salmon and sea trout in Scotland ended around the end of October, although it is difficult to know exactly because every river catchment has its own season. Whatever the date the fishing ceased completely, it will be April 2021 before the official catch data is published. This is nearly six months after the end of the season and nearly one and a half years since the first fish of 2020 was caught.

In these days of instant data, it seems incredible that catch data for every river in Scotland cannot be posted on a weekly basis. Anglers only need to report their daily catch to the proprietor at the end of the day and the proprietor to load the data at the end of the week. Its not exactly rocket science.

Equally, there are three organisations campaigning for wild salmon in Scotland, FMS, AST and S&TC. If Norske Lakseelver can publish an accurate interim report in Norway, why cannot these organisations do the same in Scotland? Admittedly, FMS do report on a few selected rivers in their Annual Review, but the data is somewhat basic.

Added into this mix is the fact that Marine Scotland Science’s official report published in April has been significantly truncated. They used to report on 109 fishery districts, but this has been reduced to just over 50 with many of the smaller districts being amalgamated together.

This change was instigated because one proprietor complained that information about his/her fishery was private and covered by GDPR. Although it is impossible to identify proprietors from the catch data, it seems that their interests take precedence over those of the salmon and sea trout. (This question is now being considered by the Scottish Information Commissioner). Measuring catch trends that have covered over sixty years of data are no longer possible because the data is no longer available. I have heard of not one complaint from the wild sector over this restricted access to data yet the wild sector demand ever more transparency from salmon farmers.

Meanwhile, the closure of the farm in Loch Ewe, which S&TC have (wrongly) long blamed for the collapse of the loch Maree sea trout fishery should present an opportunity to monitor whether the fishery recovers. Unfortunately, the Ewe system is no longer identified in the catch statistics as a separate fishery and thus any data about catches is no longer available for public scrutiny.

Will the REC Committee be asking whether salmon farm data is equated to wild salmon catch data as a measure of whether there is any impact? I very much doubt it. The REC Committee will only be interested in what measures the salmon industry has taken to increase its transparency. The whole purpose of holding the inquiry, which was initiated to advance the protection of wild fish, will have been long forgotten. The salmon farming industry is just the sacrificial scapegoat for the problems of the wild fish sector. Maybe the REC Committee should be looking at wild fish, rather than farmed?

Their word?: Salmon & Trout Conservation recently posted a statement on their website saying that the recommendations of the Salmon Interactions Working Group will not work … but don’t just take their word for it.

Instead, they offered comments made by 1. the Chairman of the Wester Ross Salmon Fishery Board who is also a board member of Fisheries Management Scotland as well as an employee of the Atlantic Salmon Trust, 2. Fisheries Management Scotland and 3. An unnamed senior executive from the Crown Estate, all of whom S&TC say question the viability of the SIWG proposals. ST&C repeat the words – “But don’t just take our word for it” – four times.

Well, Salmon & Trout Conservation can rest assured, I, for one, don’t take their word for it at all. How can anyone take the word of an organisation that refuses to discuss the issues with anyone who disagrees with their view and gets abused in the process for trying to do so.

The reasons S&TC give as to why SIWG won’t work are simply a rehash of their usual narrative. For example, they say that SIWG rejects the standard precautionary approach in which the burden of proof that there is any damage is the sole responsibility of wild fish interests. They say that this is contrary to the basic principles of natural justice – but don’t just take our (their) word for it. They cite the Wester Ross Salmon Fishery Board who questioned a planning application to expand a farm saying that the farm should show that a previous increase in biomass was not associated with further declines of catches of wild fish stocks in the area.

This highlights the fundamental problem of the wild fish sector. They don’t think that they need to prove that salmon farming is causing damage to wild fish stocks but at the same time whilst they say that the salmon farmers should show that they are not the causing the declines, they refuse to listen when such evidence is presented.

I would like to cite the example of the Fishery District around the River Fyne which empties into the Loch of the same name.

The late Bruce Sandison was an authority of salmon fishing in Scotland. He wrote a definitive guide on where to fish – Rivers and Lochs of Scotland, which is often described as the angler’s bible. In the last edition (2014), Mr Sandison writes about the Fyne:

“up until 1989, the River Fyne was capable of producing between 200 and 250 salmon each season, in spite of the impoundment of the head waters for hydroelectric power generation purposes. However, recent years have seen catastrophic collapse of salmon numbers caused by the prevalence of factory salmon farming in Loch Fyne, which have brought salmon stocks to the point of extinction.”

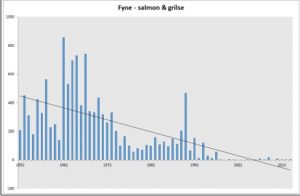

The following graph shows the catch data for salmon and grilse from the Fyne fishery district.

The catch data clearly shows that the River Fyne fishery was in decline from the mid-1960s; at least twenty years before the first salmon pens were established at the head of Loch Fyne in about 1985. Catches reached a low by 1977, which was due to the combined effect of two hydro schemes associated with the river. Catches continued until the late 1990s and then ceased, likely because anglers had heard that the fishing had been destroyed by the hydro schemes. However, Mr Sandison blamed the arrival of salmon farms to the loch. This was certainly not the case, as the farm at Cairndow was well known to be situated in an area of high freshwater flow and thus did not suffer at all from sea lice. Two more farms were set up further down the loch in 1988 and 1989, but by the time these farms were fully operational, it can be clearly seen that the fishing had already been destroyed. Bruce Sandison adds that the River Fyne is now closed to fishing, which means that there is no catch data being generated. It does not mean that the river does not have any fish.

Unfortunately, the debate about the impacts of salmon farming on wild fish has gone on for far too long. This is for one simple reason and that is that the wild fish sector refuse to actually discuss the specific impacts. The Salmon Interactions Working Group was the ideal opportunity to do this, but it turned into a missed opportunity. Their April 2020 report states ‘we saw little point in summarising what has already been said’ but they refused to discuss what hadn’t been said. The group refused requests to make representations from outside the group. How can any group form new opinions if they only hear their own voices? I do realise that the group included industry representation in the form of the then industry representative organisation CEO but would suggest that someone with better qualifications and more experience might have been better suited to participate in the group.

I am planning to revisit SIWG in the near future, but it is interesting that when referring to wild salmon data, SIWG recommends to collect and report wild catch data – as far as possible yet such conditions do not seem to apply where farmed salmon data is concerned. The reality is that Marine Scotland Science send out about 2000 forms to river proprietors each year of which 90% are returned – why this should not be mandatory so every form is returned is unclear, but there is no reason why those monitoring catch data should not be able to access the catches from every beat of every river in Scotland. What is the big secret that data has to be amalgamated into single or multiple catchments preventing the data from being examined and understood?

I seem to agree with S&TC that SIWG may not work but that’s because the same rules do not seem to apply to both the farmed and wild salmon sectors when it comes to openness and transparency and on that – you will have to take my word for it.