Take it as read: Fisheries Management Scotland have tweeted an update about the red skin disease found in wild salmon. This was first seen in Scotland in early 2019 but has been observed across Europe. Samples have been sent to Marine Scotland Science laboratory but as yet, the cause of the disease remains a mystery. However, FMS say that one potential theory under scientific investigation is whether a dietary deficiency among certain salmon stocks or sub stocks is related to the disease but that the investigations are so far inconclusive.

Regular readers of reLAKSation might remember that I discussed this very issue last year and highlighted that red skin disease in salmon stocks in the Baltic had been associated with a deficiency of vitamin B1 (thiamine). I had heard about this from a colleague in Norway but in fact a scientific paper on the subject was published at the beginning of the year (Jan 9th). This is titled – Deficiency syndromes in top predators associated with large-scale changes in the Baltic Sea ecosystem by Majaneva and others.

Interestingly, critics of the salmon farming industry had been quick to blame salmon farming as the source of the disease and for spreading it to wild fish. However, farmed salmon are fed a balanced diet and are therefore not deficient in thiamine and thus should not exhibit the symptoms seen in wild fish. Thus, it seems strange that FMS say that the cause of the disease is inconclusive. However, I am not surprised. The wild fish sector in Scotland is extremely insular. They are only interested in their own view. The fact that someone from the salmon farming sector mentioned thiamine deficiency last year was probably sufficient reason to dismiss it as a cause. How many times, have I heard that only anglers really know about wild salmon?

This news about red skin disease comes as I hear that a group is being established to discuss the proposed wild salmon strategy. I have heard that the group will be ‘tight’ i.e. that it will be restricted to a few selected people, likely to be the usual ‘suspects’.

I despair for the future of wild salmon in Scotland. It could be argued that salmon stocks have declined over the last forty years under the care of the fishery boards conservation organisations and representative groups, so it seem unlikely that the same organisations will now come up with a new plan to safeguard wild stocks of salmon and sea trout. Of course, they will blame salmon farming as the main problem, but if that is the case, then they need to start providing hard evidence to support their claims rather than relying on the dubious and the circumstantial.

The Scottish Government have produced a paper outlining the high-level pressures on wild salmon. They forgot to include the blinkered vision of current management practices and the unwillingness for anglers to accept that they are part of the problem. The wild sector demands transparency from the farming sector but not from themselves. The fact that catch data is now less available than it ever used to be is indicative of the problems. Even information about how the wild salmon strategy will be determined is hard to come by. A FOI request (not made by me) from earlier this year about the wild salmon strategy is worth a look just to see how much of the correspondence has been redacted especially the later pages.

Wild salmon is clearly not for public discussion, but only amongst the selected few.

Finally, returning to the subject of red skin disease, it is interesting to see where FMS place their priorities. Their information sheet ends with the following:

“Potential risk to human health from consuming these fish? There is no suggestion at all that fish displaying RSD will have an adverse impact on human health if consumed. In light of current conservation concerns for Atlantic salmon, anglers should be mindful of the need to observe regulations on taking fish and additional voluntary measures for restraint”.

http://fms.scot/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/201001-Atlantic-salmon-skin-issues-Q-A-FINAL.pdf

Why do they even need to say this? We have clearly not yet moved away from the idea that we have to eat these iconic fish (even at £400/kg see later).

Postscript: FMS have on Friday 23rd October posted a link to the MSS map of man-made barriers that prevent salmon migrating up rivers to breed. Is it a coincidence that the same map was used in my video posted on September 13th? Is the forthcoming wild salmon strategy meeting perhaps making them think that they should be raising other issues than salmon farming?

Introgression: I have been talking to an respected fishery biologist, who mentioned that in their opinion, the fish that featured on The One Show that was described as coming from the storm affected farm, very much appeared to be a wild fish. The only significant distinguishing characteristic of the fish was its ragged fins, however, the biologist rightly pointed out that many wild fish at this time of year have been in the river for some time and their fins start to get ragged so that this specific fish was not unusual. Of course, the best way to clarify the fish’s origins is through its scales.

Since the events of Storm Ellen, Fisheries Management Scotland have issued several press statements warning anglers to be vigilant to watch for salmon emanating from the Carradale farm and asking for all suspect fish to be recorded, and scales samples to be taken. It has been some time since the storm and there have been reports of fish being captured across several river catchments. Whether the fish are from the farm or not is still unclear and just as the wild fish sector demand that the salmon farming industry is transparent, so the wild fish sector should be transparent as to the findings of these captures. The time has come for a full report to be issued stating where and when the fish were caught and their origin according to the scale reading. This report should also include all fish despatched so it can be ascertained how many fish deemed to be of farmed origin were actually wild. It takes only minutes to read a scale to see if the fish has continuous or seasonal growth, so there is no reason why this information cannot be published immediately.

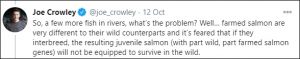

Different fish? Joe Crowley, the reporter for ‘The One Show’ who covered the story of the Storm Ellen release is a keen angler and therefore has a vested interest. He tweeted extensively when the programme was broadcast including the following:

Unfortunately, whilst Mr Crowley is happy to pose questions, he isn’t so keen to hear the answer. He says that ‘farmed salmon are very different to their wild counterparts’ and he fears what will happen if they interbreed. I would suggest that if anglers have to send a scale sample to help identify whether any salmon is farmed or wild then they cannot be that different. The angler featured in the programme seemed to imply that he could tell the difference because farmed salmon only fought against being dragged round by a hook in its mouth for ten minutes, a wild salmon would fight against this cruelty for much longer.

Regardless, the majority of fish of farmed origin appear to have been identified in Ayrshire rivers and looking through some of the past reports of the local fishery board and fisheries trust I came across an article from the trust in 2008 which should be of interest to Mr Crowley.

On 28th July 2007, a local angler caught a sea trout weighing 10lb 2oz from the River Doon. Sea trout of that size are considered to be very rare in that part of the word and whilst it would have been usually released, the fish was deeply hooked so ended up on the dinner table.

When the fish was cut open, a tag was discovered, which had been implanted by the Environment Agency. This acoustic tag records the position of the fish in the river. The last date that the fish had been recorded was 4th May 2005.

What Mr Crowley might find of interest is that the fish was tagged as a wild salmon smolt yet when caught in 207, the fish gave all appearance as being a sea trout. The scale sample was subsequently subjected to genetic analysis by the scientists at MSS Pitlochry and it was found that the fish was in fact a hybrid of a sea trout and salmon.

Such hybridisation does happen naturally, but they rarely reach this size. What is interesting is that the most important consideration given to this hybrid by the Ayrshire Fisheries Trust was that the fish smashed the unofficial world record for a salmon trout hybrid. The previous record had been held by Alan Youngson, one of the fishery scientists from the Pitlochry lab.

By coincidence, Dr Youngson has authored papers looking at hybridisation between salmon of farmed origin and trout and found that they were more likely to mate with trout than wild salmon although all the numbers were extremely small.

Finally, it is also worth pointing out that the fish was originally tagged in the River Tyne.

Get the drift: The Oban Times reports that following the events of Storm Ellen, a new muti-year study has been commissioned to gauge the impact of any interbreeding between wild and farm-raised salmon. The study of 115 sites aims to confirm the current genetic profile of wild salmon and track any changes due to interactions with farm salmon. The study will be managed by Fisheries Management Scotland and supported by Marine Scotland’s Aberdeen Laboratory.

However, this study has not been widely welcomed. The paper reports that pressure group ISSF (made up of just angling guide Corin Smith) said that ‘the horse has already bolted and that it is already well established that farmed salmon have a devastating impact on wild populations’. ISSF say that wild fish are paying the price for mass escapes.

Sadly, Mr Smith’s comments are an example of a lack of understanding of the science and part of the trend of simply quoting others who have expressed the same misunderstandings.

The impression of salmon genetics given by the wild fish sector is that salmon from different rivers have a different genetic profile that make them unique to that river. The largest rivers might even have tributaries where the salmon are different to others in the same catchment.

Sadly, this idealised view doesn’t exist and in evolutionary terms doesn’t make sense as it would lead to inbreeding and weakening of stocks. The reality is that the salmon might return to the same river based on not the genetics but rather their magnetic positioning and the taste of the water. Often, they get it wrong and stray into other rivers and this helps the strengthening of the gene pool.

I have recently discussed FASMOP in reLAKSation. This was a £1 million study of serval river catchments to identify genetic differences. FASMOP is never mentioned now and this was because it failed to identify the expected differences in genetic make-up. At the time, this failure was blamed on the methodology but why this was not tested prior to spending this money is unclear.

Mr Smith says that it is well established that farmed salmon have a devastating effect on wild populations. It is often said that such interactions will lead to a collapse of the wild stock. This theory comes from research papers published during the early 2000s. At the time, it was suggested that repeated releases of farmed salmon on a regular basis would maintain a pressure on wild stock that might eventually lead to the loss of their genetic profile. However, this forecast failed to materialise and instead, whilst unfortunately, incidents still happen, they are few and far between. FMS state in their objection that there have been three large incidents in six years. Of these, most of the fish will have been lost at sea with very few making the journey up the river and even fewer breeding. Any resulting fish with unfavourable genes will not be subject to Darwinian process and will be uncompetitive. Even though there are very few incidents, those like Mr Smith who blame salmon farming for every problem of the wild fisheries sector, still maintain this discredited extinction theory.

Salmon & Trout Conservation cite one of these papers in their objection to a new salmon farm in Argyll. There is a strong angling influence on some of this research and interestingly, one of the paper’s authors has started to write for one of the angling magazines. Some of the claims made about salmon farming n recent articles by this author are completely unproven and lead to questions over motivation.

Finally, Mr Smith suggests that studies on salmon genetics may be too late and he may be right but not because of the salmon farming industry. Several years ago, I raised the subject of genetic drift and its influence of wild salmon genetics. I still hold that genetic drift has likely to have had a much greater influence on salmon genetics in Scotland than anything else.

Under normal circumstances, salmon genes are under the control of Natural Selection with those genes that provide the greatest benefit that prevail. This is known as survival of the fittest. However, changes in the gene pool can also occur without such evolutionary influence. Instead, changes can be simply down to luck. This is genetic drift.

To illustrate the difference, consider the situation when an angler tries to catch a wild salmon. The fish that manage to avoid capture do so, not because they are better adapted through natural selection, but rather because they were lucky. Catching a salmon is a random act and as many anglers will say, very unpredictable. This random loss of genes when a salmon is caught and killed is simply a matter of misfortune. This random process is described as genetic drift.

Since 1952, 5.9 million wild fish have been caught and killed by anglers. All these salmon genes have been lost to the gene pool simply down to bad luck. Many more were lost through netting, but none were lost due to natural selection. All were lost due to bad luck. The outcome is the gene pool has been significantly influenced but in a very unpredictable way.

Every salmon lost to the stock is a loss to salmon’s genetic diversity. Sadly, anglers do not see that their actions, over many years, have contributed to one of the greatest losses of salmon diversity and instead prefer to deflect attention to much less significant causes.

Finally, this long-term change to genetic diversity must be also considered against the wider changes affecting animal and plant populations due to climate and other underlying factors. For example, the number of returning salmon across the north Atlantic range has dropped from 20% in the 1980s to less than 5% now. This is not a consequence of salmon farming and this determined effort by anglers to focus attention on salmon farming simply prevents consideration of many other issues.

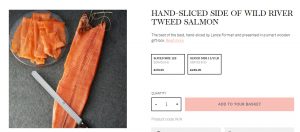

How is this possible: A regular reader of reLAKSation asked me the question ‘How is this possible?’ He had been looking at the Forman & Field website and came across ‘Hand-sliced side of wild River Tweed salmon’.

This is described as:

“Wild salmon from the River Tweed is the best of the best, from the most celebrated of salmon fishing rivers. These limited-edition sides come in a very smart wooden presentation box with a numbered certificate and are sliced by Lance Forman himself.

Wild River Tweed Salmon is now so fiercely protected – and fishing so restricted – that it is nigh on impossible to acquire stocks, with prices reflecting its rarity. We would urge you to order while you can, as there is a grave danger you will never experience this wonderful delicacy again.”

The price is £179.95/lb which equates to about £400/kg.

For comparison, The Good Housekeeping guide to smoked salmon for Christmas recommends Bleikers peat smoked salmon as the best choice which is priced at £45.00/kg although it is available now for £3.95/100g.

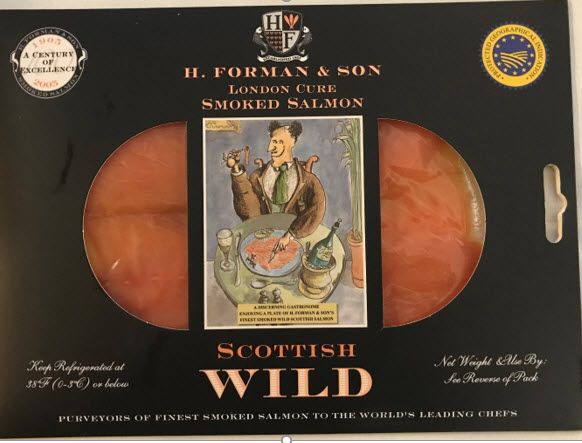

Interestingly, I was involved in a major survey of smoked salmon in the UK last year and I bought Forman’s Scottish wild smoked salmon for £15.99 for 100g or £159.90/kg. The pack did not state the origin of the fish other than it was caught from the North East Atlantic. Whether this was correct is unclear because to answer the original question as to how this is possible when commercial netting of wild salmon in Scotland is banned, the answer is that it is only coastal netting that is banned.

The fact is that organisations such as Salmon & Trout Conservation who claim credit for the closure of coastal netting forgot about the commercial river nets so these are licensed to operate in four rivers – Tweed, South Esk, Berridale and the Nith. However, only the Tweed and Nith produce a significant catch.

In 2019, a total of 526 salmon and grilse of average weight 6lb were caught from Scottish rivers. In addition, 689 sea trout were also harvested, and these had an average weight of just over 3lb each.

It’s quite surprising that the angling sector has not tried to shut down these fisheries but of course they are so busy attacking the salmon farming industry that they must think the sacrifice of 1,200 fish that could be caught and killed by anglers instead of commercial fishermen is a price worth paying.