Silver on black waters: Last week, anti-salmon farm campaigner, Corin Smith, used the Easter break to promote his September 2019 report ‘An Autospsy of an “All Clear”’ which had been prompted by events in the River Blackwater in the summer of 2018. About eighty wild salmon died in the river, which according to Mr Smith was due to stress induced mortality most probably due to intense sea lice infestation. Mr Smith records that some of these salmon were carrying up to seven hundred sea lice; numbers which according to Mr Smith had never been seen in wild salmonids in Scotland.

Mr Smith also says that ‘standard distribution’ suggests that many hundreds more wild Atlantic salmon would have suffered considerable impacts from such elevated levels of sea lice which could lead to the prospect of significant numbers of wild salmon dying further afield without being recovered or reported. He said that such infestation could represent an existential threat to a historic run of perhaps only 1000 -2000 wild salmon originating from the River Blackwater.

The Fish Health Inspectorate took some samples from the dead fish taken from the river but were unable to determine the cause of death. Mr Smith reports that all the dead fish carried visible signs of sea lice and as local anecdotal evidence suggested that the local salmon farm was also suffering from high lice levels, then in Mr Smith’s view, the link was established.

I have written previously about the events on the Blackwater and what Mr Smith chooses to omit is that fact that these fish were trapped in a shallow sea pool as they were unable to move up the river due to a lack of water. This is not the first-time migrating salmon have been stuck in this pool although the outcome then was quite different.

On this occasion, it seems that the fish suffered sunburn due to the local conditions. At the same time, the normal numbers of sea lice on the fish exploded due to the warm water taking advantage of the sunburnt skin. There are no reports from any other river system of adult salmon picking up large numbers of lice during the short journey past salmon farms to freshwater. The sea pool was fished for salmon for some weeks which would not have continued had the fish had been noticeably suffering. Local concern was only expressed a day or two before the fish started to die.

I would also like to refer to Mr Smith’s comment that standard distribution suggests that many hundreds more salmon would be suffering too, except that all parasites including sea lice do not follow standard distributions. Instead, they are aggregated, meaning that just a few hosts carry a high number of parasites whilst the majority carry none or one or two. This is biological reality not a fanciful idea.

As I mentioned, this is not the first time that salmon have been caught in the sea pool when the river is running low. In December 2012, The Herald newspaper reported that the Garynahine Estate on the River Blackwater landed the most salmon since records began in the late 1800’s. The paper says that gamekeeper Donne Whiteford thought that the haul of 258 fish in 2017 was exceptional at a time when the five-year average was 116. However, in 2012, the catch was 555 fish.

Mr Whiteford told the newspaper that there had been a two-month drought before the season began with what he described as desperate fish leaping as they were trapped in the pool. He was concerned that there might have been too little oxygen in the water. The Herald continued that before long visitor numbers nudged up and they did well on day ticket sales.

By coincidence, Mr Whiteford reminisces about this record catch in the latest issue of Trout and Salmon magazine in a seven-page spread which features this hidden gem of a classic little spate river. The article was the result of a visit to the river in June 2019, a couple of months before Mr Smith published his report.

The article’s author is also a fishing guide and he writes that it is important that ghillies are optimistic about the prospects of catching a fish but also to manage expectations. He says that Donnie Whiteford was honest about their chances but reflected on familiar problems experienced by the fishery. Mr Whiteford said that poaching used to be a real problem but has diminished in recent years. He said that fish numbers have declined but it is not critical yet adding that aquaculture has an negative impact with a large farm in East and West Loch Roag ‘dangerously’ close to the mouths of several rivers He said that they also have a problem with grey seals.

That mention of aquaculture was the only time it was discussed in the article which was mostly devoted to fishing flies and the best pools to fish. Although the author did not manage to land a fish, his photographer caught a ‘lovely bright 8lb hen’ salmon. Later in the day, another visitor caught a four and half pound sea-liced grilse. The mention of sea lice refers only to the fact the fish was fresh in from the sea and carrying one or two lice, not that it was suffering the type of infestation Mr Smith believes is rife in the locality.

The article ends by mentioning that the Garynahine Estate offers three and a half miles of double bank fishing with 23 named pools and more than 40 trout lochs. Salmon are usually caught from late June to mid-October and for those who would like to try a different sport, the Estate offers driven woodcock, grouse, and snipe as well as wildfowling and deer stalking.

Unfortunately, the article does not really impart any insight into the Blackwater river, so I have turned to a book written in 2005 entitled ‘The Salmon Rivers of the North Highlands and the Outer Hebrides’ for some greater detail. The entry for the Blackwater considers the ownership of the estate from around 1852. Most of the history is not relevant here except to note that the tenant from 1852 to 1870, the Reverend George Hely-Hutchinson wrote about his frustration with the level of exploitation by the bag nets in Loch Roag at times of low water. This is almost reminiscent of the exploitation of the river at times when fish are trapped in the sea pools by low water.

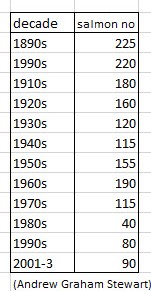

The book was written before the 2012 record catch, but it does list average catches from 1891 onwards with a 100-year average of 141 salmon per season. On the negative side, the book draws attention to the loss of all the sea trout. In the nineteenth century the book says that sea trout were extraordinarily abundant however current levels of sea lice on fish are described as being horrendous and this is ascribed to the fact that Loch Roag is now one of the most intensively farmed sea lochs in Europe. Such comments are not surprising given that the author of the book is Andrew Graham Stewart of Salmon & Trout Conservation and leader of the campaign against salmon farming in Scotland.

However, the most interesting aspect of the entry about the Blackwater in Mr Graham Stewart’s book is his reference to sweep netting in the mouth of the river. He writes that the local netting rights were exercised irregularly in the 1980s but that since 1987, there has been no commercial netting in Loch Roag. Unfortunately, Mr Graham Stewart does not say why.

The rod catch data provided by Mr Graham Stewart shows a decline in catches during the 1980s but Mr Graham Stewart says that this was due to the estate being turned into a time share that failed with the implication that there was reduced fishing effort and hence lower catches but equally this might also lead to more fish being caught by nets had the netting continued. Yet the netting ceased in 1987.

Often the blame for declining stocks of salmon is attributed to the presence of salmon farming and Mr Graham Stewart writes about the impacts on sea trout in the paragraph before discussing the netting. However, in 1987, there was no salmon farming in Loch Roag. The first farm was opened in 1989 in the western part of the loch, well away from the Blackwater. The eastern part of the loch opened to farming in 1992, six years before the third farm was established. If netting ceased because it was no longer considered viable then salmon farming was not the cause. This mirrors the experience of much of the west coast. Unfortunately, my attempts to track the closures of west coast netting stations have been thwarted by Marine Scotland’s new policy on data protection. I was told that they don’t have the resources to do this work themselves, yet they are helping fund the £750,000 west coast tracking project. A fraction of that amount would go a long way in helping understand salmon stock trends in the past and identifying whether salmon farming really does have an impactor not.

Unfortunately, the catch data statistics has never been sufficiently detailed to identify the catches from the Blackwater river. The only data available comes from the Loch Roag fishery district as a whole. The catches for the five years from 2014 to 2018 (The data for 2019 has still to be published).

Despite all the claims from the angling sector, catches for both salmon and sea trout appear to have held up well, especially considering that east coast catches have largely crashed. The numbers include a total of 573 salmon and grille and 149 sea trout that have not been returned to the water but rather killed and retained.

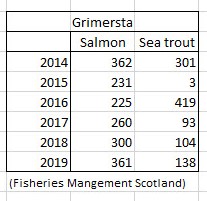

Whilst data for the Blackwater is not available, Fisheries Management Scotland include a report from the Grimersta system in their Annual Review. This fishery empties into Loch Roag so is likely to be included in the Loch Roag data.

Salmon and grilse catches have held up, but the sea trout catches have been mixed. In 2015, this is attributed to a lengthy period of bad weather. The reports in the FMS Annual Review do not mention salmon farming until 2018 (2019 Annual Review). This states that ‘salmon mortalities and very high lice numbers in the fish farms posed major concerns, yet despite such concern, 300 salmon were still caught in the Category 1 river together with a total of 870 salmon in the wider Loch Roag fishery district. This is the year when Corin Smith implies that salmon could be dying from high lice infestations across the region. In the latest Annual Review, the Grimersta report states that there were fewer issues with sea lice than in 2018 partly due to it being the first year of production cycle. In addition, reference was made to higher water which meant that the fish were able to enter the river with ease.

The fact that the farms had fewer issues with lice doesn’t seem to have made that much difference to the catches but I will have to wait until the new data is published by Marine Scotland to see what impact if any this has had on catches throughout the whole fishery district. The Grimersta Estate has certainly seen improved catches of salmon and grilse over the last four years.

In this time of social isolation, I wonder why I alone appear to be raising questions about what the angling sector say and what we actually see? The data simply does not support many of the allegations made by the wild fish sector. This last year, the salmon farming industry has been involved in the salmon interactions group; the final report of which has yet to be published. Will this show that the salmon farming industry has simply accepted the claims or have they stood up to the continued allegations about the impacts of salmon farming. The fact that the industry appears willing to fund the wild fish sector does not fill me with any confidence that the anglers have been effectively challenged.

I have heard that funding has been directed towards FMS because they are perceived to be the more moderate arm of the wild fish sector, unlike Salmon & Trout Conservation who are considered more radical.

Salmon & Trout Conservation have obtained coverage in the latest Trout & Salmon magazine regarding their campaign to tell consumers to boycott farmed salmon, especially over the Easter period. The magazine lists all the organisations that support this campaign including North & West District Salmon Fishery Board, which is of course one of the member organisations of Fisheries Management Scotland. So much for moderation?

Fifty-Five?: The lead author of a new paper that has been published in the British Ecological Society’s Journal of Applied Ecology has tweeted that ‘Salmon lice caused a 55 times higher mortality to migrating Atlantic salmon’. This is the headline finding from a new paper that looks what happens to wild fish when there are high lice densities on farms. This paper will be undoubtedly considered like manna from heaven by the wild fish sector as further proof of the impacts of salmon farming on wild fish stocks. However, a look behind the headline tells a different story.

The authors released treated and untreated smolts into a Norwegian fjord system at times of what they describe as low or high infestation pressure. This was determined by stocking 4 sentinel cages dotted about the fjord with 25 fish each. Two different releases of fish, one at low pressure and the other at high pressure were made over two years. What is interesting is that the release dates are the same for both years, May 18th and June 9th. These dates are only three weeks apart, yet this length of time is considered to be sufficient to differentiate them as periods of low and high infestation. The reality is that the proximity of these dates mean that they should be considered to be the same release.

There are also some questions about the fish used in the release. The 2013 fish were 66% bigger than those used in 2104 and undoubtedly, this could influence the results. In addition, the fish were reared at a facility a long way from the release site. After transport to the release site, the fish were allowed just 48 hours to adapt and imprint on the local water. It is possible that many fish did not return for this simple reason

In the previous commentary, the Estate Manger from Grimersta writes that there were fewer issues with lice because the farms were in the first year of production. The theory is during the first year, the fish are smaller and infestation rates much lower. This is based on some work conducted by the Lochaber Fisheries Trust from 2002 to 2009 when they found lice infestations on sea trout were lower in the first year of farm production. I have looked at how this relates to wild fish catches near some farms and cannot see a definitive connection. However, given this background, a comparison of fish released between the first and second year of production might be more relevant.

What is interesting from this new paper is that whilst they found a significant difference in the returns from fish released at a time of high infestation in one year, they did not in the other. The June 2013 release recovered 99 treated fish and 94 untreated fish. Both are remarkably similar numbers, but by comparison, those of fish released in June 2014, seventy that returned were treated fish and one was untreated. The authors admit that this result was exceptional even when compared against the two 2103 releases. These were 27 treated and 75 untreated in May 2013 and 97 treated and 86 untreated in May 2013.

This one exceptional result is in my view insufficient to make any conclusions at all and certainly one that could have a significant impact on the salmon farming industry.

One of the advantages of obtaining papers on-line is that it is possible to also access the data set from the research. What this data shows is that if the returns are combined, then the split between treated and untreated fish is 55:45 with just 1.87% of the fish returning. This is hardly significant.

The authors report that the highest mortality was 99.7% whereas protected fish suffered 98.1% mortality. In the general run of things, the difference is minimal. Could it be that if these researchers are concerned about the number of salmon returning to breed then instead of directing their time at a mortality difference of 1.6%, they would be better employed looking at what happened to the other 98% of smolts that failed to return. This level of mortality is now the normal even in areas where there is no salmon farming.