Thank you: The third week of the COVID crisis and I just would like to thank everyone who has written in to say that they look forward to the weekly mailing as a welcome diversion. I did think that with the current lockdown, there might be little to comment on. In fact, this week the opposite is true especially about wild fish interactions. I continue to watch the markets but as it seems that no-one else is standing up to counter the claims emanating from the wild fish sector, I continue to take on this mantle. Meanwhile, everyone please stay safe.

What’s missing: Given that fishing for salmon is no longer possible, I might have expected to hear from the wild fish sector that this is a unique opportunity to give salmon populations a break from the pressure of exploitation and perhaps should be extended after the crisis to allow stocks to recover. After all, demands have been made that wild salmon should be a national priority.

Unfortunately, not a word about how reduced exploitation will help protect wild stocks instead, Salmon & Trout Conservation put out a press release on behalf of the Missing Salmon Alliance demanding a new system of regulation for fish farms in Scotland.

The press release states that the Missing Salmon Alliance (S&TC, Atlantic Salmon Trust, The Angling Trust and the Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust) are fighting to reverse the devasting collapse in wild salmon around the UK. In what appears to be their first press release since their launch in November last year, they are focusing on something that, at worst, could impact on less than 10% of the Scottish catch. This demand for stronger regulation will have no affect at all on the 90% of wild salmon that are in decline in other Scottish rivers as well as elsewhere in the UK.

Such regulation as they demand is unlikely to have any impact on local wild stocks let alone those elsewhere. It is just that the wild sector cannot let go of their view that salmon farming is the greatest threat to wild salmon stocks in the UK.

The Missing Salmon Alliance have made seven demands which include:

- A defined public authority responsible for protecting wild fish from salmon farms.

- The introduction of an effective, robust and enforceable regulatory system.

- A genuinely precautionary approach to licensing salmon farms.

- A review of existing biomass and location of existing salmon farms.

- Full transparency on the environmental impact of fish farming.

- All new farms subject to rigorous cost benefit analysis on impact of local businesses.

- Adaptive management of fish farms to be based on monitoring of wild fish.

There is much to discuss in these demands, but I want to focus on just one at this time. The transparency on environmental impact mentioned in point 5 includes ‘real time’ publication of on-farm sea -lice, escapes, chemical usage, mortalities and disease information. As I read these demands, I am still waiting for the rod catch of wild salmon data for January to December 2019 to be published and this year the data will be much reduced so that assessment of catches in key river systems such as the Ewe will no longer be possible. This is because river proprietors have complained that publication of the data contravenes GDPR regulations. It seems that whilst demanding greater transparency about salmon farms, those in the wild fish sector are not so willing to share their data, especially on a real time basis.

More importantly, whilst the salmon farming industry has nothing to hide, real time data can be extremely misleading as it lacks context and context is fundamental to understanding the impacts of farming salmon.

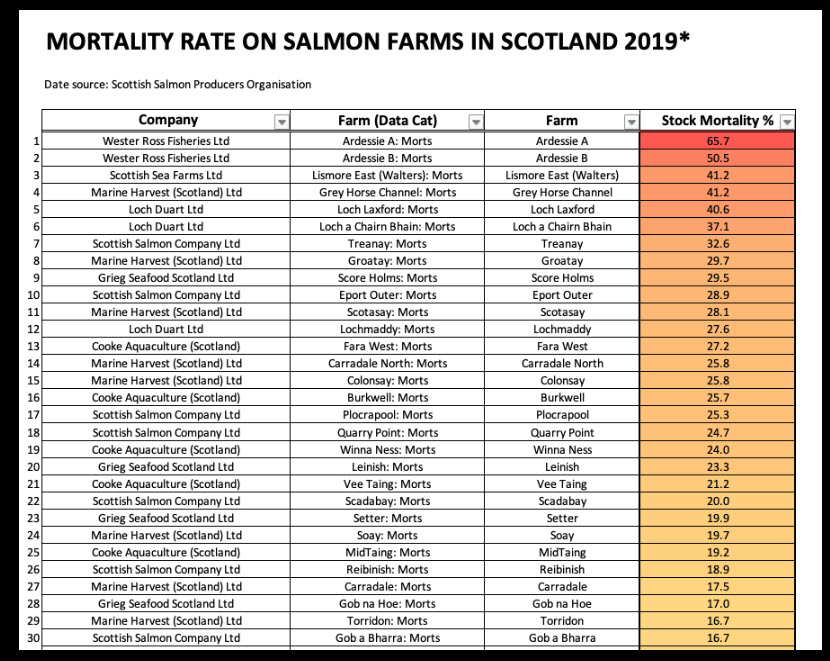

In the last issue of reLAKSation, I discussed how my initial look at the newly released SEPA data identified a disparity between claims that the industry suffers 20% mortality and the very small number of incidences where individual sites experienced such levels of mortality. I have looked again at the SEPA data and I have also looked again at the interpretation of the data made by salmon farming critic Don Staniford who lists 95 sites with the highest mortalities in any month by weight. His is not the only reference to mortality data published by industry critics. The press release referred to above was issued by Corin Smith of the S&TC who also runs his own anti-salmon framing website and Facebook page. Last year Mr Smith published some tables highlighting salmon mortality at certain farms. The two tables for 2019 list 59 sites with mortality levels ranging from 65.7% to 2.7%. He also provides an explanation which I will discuss later.

As mentioned, there is a difference between the way that Mr Smith and Mr Staniford present their data. Mr Smith’s data appears to be the annual mortality for each site, whilst Mr Staniford lists separate mortality events by site. This means that any site might be listed more than once if fish died over a two-month period. It also does not account for the size of the site. Mr Staniford’s tables come directly from the SEPA data.

My first observation is that only two of the sites that appear on Mr Smith’s list also appear on Mr Staniford’s. This means that 57 sites highlighted by Mr Smith are not included in the 95 highest mortality incidents in Scotland. This is rather puzzling as sites with up to 65.7% mortality must have had high mortality incidents but seemingly not.

Mr Smith’s list of ‘Mortality rate on salmon farms in Scotland 2019’ refers to its data source as coming from the SSPO rather than from the SEPA list. I also noticed that the tables produced by Mr Smith for 2019 were published on his Facebook page dated 18th November 2019. Thus, it is likely that however he calculated the values for his tables, they do not include mortalities for the months of November and December.

Mr Smith includes an explanation about the data saying that the SEPA data is based on mortality by weight and includes the monthly biomass. Mr Smith says that mortality is also measured by the actual number of fish dying and in fact the SSPO say on their website that this is how they calculate industry mortality figures. Mr Smith says that he prefers this method because the fish can be between 4-6kg at harvest, but most mortalities occur when fish are much smaller.

However, as the SEPA figures are reported on a monthly basis the biomass will reflect the smaller size of fish so I would argue that measurement using SEPA data is just as valid as long as everything is treated in exactly the same way. In fact, I recalculated the SEPA data for 2019 and compared it to the monthly figures produced by the SSPO and they are almost identical. I am therefore satisfied that the way I have treated the data has validity. The SSPO report monthly mortality data for 2019 ranging between 0.83% and 2.79%. My calculations range from 0.98% to 3.28%.

Mr Smith does not explain how he arrived at the figures in his table however, I have tried every way possible to calculate anything that comes out so high. I have looked at the first 22 farms in his list, which all have a mortality of 20% or above. I was unable to include four of the farms as the names do not match those in the SEPA list (I am sure it would be possible to reconcile this but this will require a great deal of time due to the large number of farms).

I calculated the annual mortality for each of the farms and whilst Mr Smith rates these as being between 65.7% down to 20%, my calculations range from 4.33% as the highest down to 0.46% as the lowest. Interestingly, the two farms with the highest mortality on Mr Smith’s table were the two that I found to be the lowest.

Finally, I would just mention that Mr Smith also points out that since 2002 mortality rates for the industry have increased from 3% to 14% based on his calculation. Over the same period, I found an increase from 0.74% to 1.76%. Mr Smith says that the actual figures don’t matter as much as the trend yet at the same time he says that the lower figures he quotes are at odds with the 20% often quoted for the industry. He says that this is because the 20% is based on fish number not weight. He adds that this is the figure that is widely quoted and has been accepted by the industry. I am not sure where Mr Smith gets this idea for clearly none of the data seems to support his view.

The main conclusion of this analysis is that there is little point producing real time data if there is no real understanding of what it means. When it comes to salmon farming, it seems that if one site suffers from an unusual mortality incident then this is enough to suggest that it is typical of the whole industry.

Tracked: The Atlantic Salmon Trust were supposed to have held their Spring Conference this week but as it was cancelled, they have released a video update instead:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rhp07X-mzqU

One of the subjects covered was the Likely Suspects Framework. Likely suspects highlighted included Forestry/Agriculture, Avian predation, Estuarine predation, Coastal nets and aquaculture, Marine predation and Marine exploitation. One likely suspect that they seem to have missed out is freshwater exploitation but long ago, they dismissed angling as having any influence on wild fish numbers. The fact that anglers have killed 5.9 million wild fish from Scottish rivers over the last 68 years has had absolutely no impact at all. The AST have peppered their video with the hashtag #wildsalmonfirst but I wonder whether #salmonanglersfirst might be more appropriate.

As well as providing an update to their east coast Moray tracking project, they also provide details of the new west coast tracking project. This is a collaboration between the AST, Fisheries Management Scotland and Marine Scotland as well as the University of Glasgow. The aim is to tag 800 smolts across 8 west coast rivers in the hope of identifying key migration routes with the aim of significantly reducing the risks to salmon smolts. The video points out that this project will run alongside other projects already underway on the west coast where there is now more tracking taking place than ever before. It seems that any new wild fish research must now involve a tracking study to have any validity.

However, the most interesting part of the video comes towards the end in the section titled – ‘Can the Atlantic Salmon Trust’s work influence policy?’ In this section, the AST states that it is their aspiration that both the east and west coast tracking projects provide enough evidence to influence Government policy to help recover salmon stocks. They say that from the east coast work, they would like to change the Government’s approach to bird predation and they hope that the data will support this aim. They envisage that the west coast project will deliver vital evidence which will lead to future reform of fin fish aquaculture regulatory system.

This seems to suggest that those running these tracking projects already have a preconceived idea of what they hope to achieve even before they have the evidence. I have written in past issues of reLAKSation that the only reason for undertaking a west coast tracking project is to try to influence policy on salmon farming. I can only again stress that salmon rivers within the aquaculture zone have never accounted for a significant proportion of the total Scottish salmon catch. Even the most Draconian regulation of the salmon farming industry is not going to bring wild salmon back to most Scottish salmon rivers.

Of course, the wild fish sector has always argued that they can only influence a few aspects of salmon survival and hence their fixation with salmon farming. This is why the wild fish sector are not interested in anything else that might be to blame for the decline in wild salmon. They say that they cannot change climate change so is makes no difference if it is the main reason why salmon are in decline.

What is worrying about this approach is that Fisheries Management Scotland are of the key members of the west coast tracking project and yet the Scottish salmon farming industry are soon to announce news of their investment, as discussed in a previous issue of reLAKSation. This investment will provide significant funding to FMS to help investigate the decline of wild salmon in Scotland. Is the west coast tracking project of which FMS is part, ultimately going to be used against the salmon farming industry to impose more stringent, but unnecessary, regulation rather than uncover why wild salmon stocks are in decline across all of Scotland?

Netted: One of the likely suspects highlighted by the AST is coastal netting. However, such netting is no longer possible in Scotland, so can now be dismissed as a suspect in the ongoing decline. Yet, netting is still on my radar. By coincidence, BBC Scotland broadcast the independent film ‘Of Fish and Foe’ last weekend and is available on iplayer for the next three weeks https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/m000gzv8/of-fish-and-foe. It is definitely worth a watch if you have not seen it.

Also, by coincidence, one of my regular correspondents sent me a link to a short film about netting on the Isle of Skye filmed in 1938. This is a really interesting window into a world gone by: https://player.bfi.org.uk/free/film/watch-salmon-fishing-in-skye-1938-online

It is easy to forget that whilst the more recent focus has been netting on the Scottish east coast as featured in the film Of Fish and Foe, there used to be netting stations all along the west coast as illustrated by the film ‘Salmon Fishing In Skye’. Many of these nets disappeared long ago but it is unclear exactly why. There doesn’t appear to be much information about west coast nets and my only knowledge comes from a meeting with a retired gentleman from the Loch Ewe Estate who helped out with the local nets. He told me that the netting station closed down in the very early 1980s simply because they weren’t catching any salmon. This was at least five years before salmon farming came to Loch Ewe and became the scapegoat for the decline of local fish stocks.

If the nets in Loch Ewe closed down in the early 1980s, then an obvious question would be what happened to the other netting stations. When did they close down?

Whilst there appears to be little written information about west coast salmon netting, one possible source of data would be Marine Scotland’s catch statistics. Whilst, I have looked at rod catches, netsmen have also been obliged to submit catch returns every year since 1952. Obviously, if a netting station that had been submitting an annual return every year suddenly stopped doing so, it might be an indication that it had ceased to operate. By looking at all the catch returns, it would be possible to plot the closure of west coast nets and hence provide an indication of the state of local salmon stocks.

This seemed a simple project, but it has proved to be far from it. Firstly, it seems that much of the early data exists on paper only and this would require someone to go collect the data from each record. I was told Marine Scotland Science don’t have the resources to get someone to do that. I offered to do it myself, but it seems that this is not possible as the records contain confidential information (could this not be resolved with a confidentiality agreement?) I was then told that the data is protected by GDPR even though I was only interested in data up to 1990, or no more recent than 30 years ago.

After some discussion, MSS offered to provide an indication of the number of netting stations operating in certain fishery districts in three decades. However, this didn’t indicate specific netting stations and was therefore of little help.

The west coast tracking project is costing £750,000. By comparison, a study of the closures of west coast netting stations would incur a fraction of the cost. Sadly, no-one else appears that interested and that might be because such a study might indicate that salmon farming is not the cause of west coast declines.

I would mention that I think that the closure of netting stations might provide an indication of wider issues rather than being the cause of the decline. Equally, such research might not show anything but that is the very nature of such research. The answer is not always a forgone conclusion.