Questions, questions, questions: The Herald newspaper reports that scientist and fisheries bosses are braced for the arrival of hordes of alien salmon after an ‘explosive invasion’ of the fish two years ago. Pink salmon have a two-year lifecycle so are expected to return this year. Although much has been written about the threat of Pink salmon, no-one seems to have answered the basic question as to why they have found their way across the sea from northern Russia after they were deliberately introduced into rivers there.

The reality is that these fish have strayed from the original sites of introduction into river across northern Norway and now, for whatever reason, they have strayed across to the UK in significant numbers. However, this is not the first time that these Pink salmon have been found in Scottish rivers. Individual fish have strayed into UK waters from almost the time of original stocking around 1960. What is different now is that they are coming in much larger numbers.

Do Atlantic salmon also stray from their home river in the same way as these Pink salmon? The answer is of course they must do. It is a natural response to ensure fish stocks are rejuvenated with fresh blood to ensure survival of the fittest. In 2017, Marine Scotland Science captured 81 salmon at Armadale, fitting them with an acoustic transmitter and taking a sample for genetic analysis. Ten of the fish that the researchers managed to track were genetically assigned to east coast river but only one was tracked to there. The other nine were tracked to rivers along the northern coast. Marine Scotland Science suggested several reasons why these fish strayed but did not consider that straying is a natural process to encourage genetic mixing.

Our home river, the Mersey never had any salmon because they had been wiped out by industrial pollution but as the water quality has now improved, salmon have returned. They have done so under their own steam and not through restocking. Salmon from rivers as far apart as France and Scotland are believed to have formed the new Mersey stock. Straying has clearly played a part in recolonising our river.

The key question is if Atlantic salmon stray around the UK coast, is it not possible that Atlantic salmon also stray from Norwegian rivers in the same way as the alien Pink salmon? As the fish head south from their feeding grounds, why might they not turn left to the UK instead of right to Norway. Individual fish may simply follow others heading in the ‘wrong’ direction. It is inconceivable to believe that Norwegian and Scottish stocks are completely distinct.

We ask this question because the minutes of the Interactions Group meeting from 27th February includes discussion about escapes. This included a discussion about a paper from John Armstrong and the potential to genetically sample all salmon farms to establish the origin of escaped fish because of concerns about introgression. Many farmed fish come originally from Norwegian stock so the theory is if Norwegian genes are found in wild Scottish fish, they must have come from escaped fish. Yet, it is equally possible that wild salmon in Scotland contain Norwegian genes from salmon that have strayed from Norway. The minutes do not provide reference to Dr Armstrong’s paper, but we doubt it was the one to which we already referred (Scottish Marine & Freshwater Science Vol 9 No 5 authored by Dr Armstrong) which shows that salmon actively mix.

We can only wonder why Dr Armstrong and the people from the wild fish sector have the time to attend the interactions Group meetings to discuss minor issues as escaped salmon when they have much bigger problems to address? More than ninety five percent of migrating salmon now fail to return to Scottish rivers, and it is getting less every year. When are the wild sector going to start opening their eyes to see that salmon farming is not the problem here?

The wild sector has made salmon genetics an issue because it is another issue which can be used to criticise the salmon farming industry. The idea that wild salmon from different rivers are genetically different makes no sense for many reasons. It is interesting that we no longer hear anything about the £1 million on the FASMOP project that attempted to identify genetic differences between salmon from different rivers. Could this be because they didn’t find any? Farmed salmon are still inherently the same fish as the wild. Of course, they look different because they are well fed and have a much deeper body as a result. This does not mean they are different salmon. There have been numerous experiments to show that when farmed salmon interbreed with wild fish, the offspring are weaker than wild fish. If they are, and the jury is still out, this weakness will not survive in the wild. It will not make the salmon population weaker. Interestingly, for many years it has been suggested that escaped salmon are much more aggressive when they breed with wild fish and an escaped fish will often displace a wild fish when at the redd. Yet, the latest news is that farmed salmon only develop weak breeding characteristics in the wild.

Away from the Aquaculture Zone, the Wild Trout Trust have just Tweeted ‘Very worrying news. Sea trout stocks are now at their worst ever levels in Wales’. Welsh salmon stocks are not much better.

Also, this week, the Environment Agency and its partner organisation have called on anglers to release all the salmon they catch after publication of the 2018 Salmon Stock Assessment has shown that salmon stocks in England continue to decline.

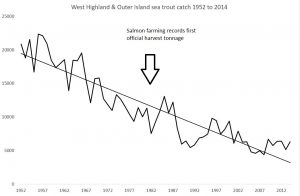

Declining stocks in England and Wales are not the result of the activities of the salmon farming industry. The wild fish sector needs to look beyond salmon farming for the cause of the problems. We, at Callander McDowell, have repeatedly published our graph of sea trout declines from the rivers in the Aquaculture Zone which shows a decline from 1952 onwards, long before salmon farming was even conceived. We have asked a very simple question as to whether whatever caused the decline from 1952 to 1982 is still responsible from the time salmon farming became established? We have not had one single response, including anything from Marine Scotland Science.

It’s not surprising that the Interactions Group rejected our request to make a short presentation to them. We ask questions that they cannot or do not want to answer.

We now question the whole purpose of the Interactions Group. The latest minutes to be posted were published three months after the meeting took place. It’s now ancient history. Even when published they serve little purpose if the various papers discussed are not provided. It seems a one-way street with various demands from the wild fish sector as to controls they want imposed on the salmon farming industry. The end game is also common knowledge and that is that Fisheries Management Scotland believe that the salmon farming industry should provide them with funds as a form of reparation.

We, at Callander McDowell now wonder whether the salmon farming industry should just give them the money to put an end to this pointless performance, even though this blood money will change nothing. The wider wild fish sector will continue to attack the salmon industry in every which way possible. FMS will spend the money on trying to control the controllables or on researching issues that are of little consequence and meanwhile salmon and sea trout numbers will continue to decline.

However, there is a ray of light on the horizon. As Atlantic salmon disappear from Scottish rivers, there is every likelihood of new sport for anglers – fishing for Pink salmon.

Smoking gun: We were in a Wholefoods store this week. They stock a wide range of smoked salmon including wild Scottish smoked salmon from Forman’s Smokehouse. There were thirty or so packs of wild Scottish smoked salmon on display, probably, more wild salmon than any angler has seen this year.

Rather surprisingly, commercial fishing for salmon and sea trout is still allowed despite a ban on netting at sea. The net and coble fisher, primarily in the Tweed and the North Esk caught and killed 3,709 salmon and grilse and 1,356 sea trout last year. Perhaps, as quite a number end up as smoked salmon selling at £15.99 for 100g in Wholefoods, it may be better to leave the fish in the water and let Wholefoods shoppers choose a different smoked salmon from their extensive range. We have tasted some of this wild smoked salmon and we think that there are much nicer smoked salmon products available and at a more affordable price.

Given that wild Atlantic salmon is red listed by the Marine Conservation Society, it is rather surprising that Scottish wild salmon is even on sale in Wholefoods stores. This is because Wholefoods have a strict policy on selling fish that is only from well managed capture fisheries. They say that ‘we don’t sell any of the red rated seafood that is found at other grocery stores.’ So why are they selling wild Scottish Atlantic salmon.

The answer is that they rely on the gradings from the Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch programme and as wild Atlantic salmon from Scotland doesn’t find its way to the US market, Seafood Watch have not given it a rating as it is not red rated by Seafood Watch, it is clearly OK to sell.

We would have thought better from Wholefoods. However, having read some of the statements on their fish sustainability FAQ’s, nothing would surprise us. One question is ‘Does sustainable seafood taste any different?’

The answer is: ‘This may depend upon the individual fish. For instance, MSC-certified sustainable wild Alaska salmon has a much different flavour profile than farm-raised salmon’

Could this be because they are different fish species? Equally, Wholefoods do not make it clear that wild Alaskan sockeye salmon has a much different flavour profile than wild Alaskan pink salmon. Perhaps it’s time for Wholefoods to get their act together on sustainability.

Taste test 1: We, at Callander McDowell, are always interested in packs of salmon from different origins that sell for different prices in the same store. This is because it happens so rarely. We recently came across two different cans of wild red salmon being sold in M&S. One is labelled ‘Wild Canadian Red Salmon’, whilst the other is labelled ‘Wild Alaskan Red Salmon’. Both cans contain Red Sockeye Salmon. Both are caught from the Pacific Ocean. Both have the same nutritional profile and both cans are the same weight. The only difference is one costs £2 and the other £2.30.

We wondered whether there is any difference in the look of the fish or taste. Both cans contain salmon that includes skin and bones. The Canadian salmon was slightly paler in colour and the Alaskan salmon was moister in the mouth.

We are not sure why Canadian salmon merits a premium price as our preference was for the Alaskan salmon, which surprisingly was the cheaper of the two

Taste test 2: The salmon farming critics continue to argue that it takes 5kg of wild fish to produce 1 kg of salmon. Whether that claim is accurate is open to debate. Whatever the actual figure, it is much less than the 12kg of wild fish that salmon eat in the wild to put on 1kg of weight.

The implication of this criticism is that if farmed salmon did not eat wild fish, then there would be much more available for other creatures to eat in the wild. This is misleading because forage fish are harvested to feed a wide range of other animals including pigs and poultry and pet cats. Interestingly, more and more wild fish is being incorporated into feeds for pet dogs and not just in small amounts.

We have just come across a new product from Devon company Forthglade. Salmon with potato and vegetables is a complete ready meal for dogs containing 75% salmon. We didn’t feel that we were up to this taste test, so we recruited Lenny to try this dog’s dinner on our behalf.

We were reliably informed that Lenny does like fish and is partial to half a can of sardines in tomato sauce to help boost his omega 3 levels, so we weren’t expecting him to turn up his nose. In fact, Salmon with potato and vegetables was a great hit with Lenny who wolfed it all down with great gusto.