Breaking news: Sea lice are probably the most contentious issue to affect salmon farming so the publication of the final of report of a monumental three-and-a-half-year study into the relationship between sea lice and the decline of wild fish stocks is likely to have been a major news story announced with all the razzmatazz from a well-oiled PR machine. Yet rather strangely, the report of this ground-breaking research was published without even the slightest peep and without our interest in sea lice, is likely to have gone totally unnoticed and probably buried without trace. We will discuss this report in a future reLAKSation, once we have time to study it in detail.

Of Fish and Foe: On Monday, we joined an audience of about forty at the Glasgow Film Festival to watch only the second showing of a new film about the life of wild salmon nets-men.

The Courier newspaper reports that director of the film ‘Of Fish and Foe’, Heike Bachelier had said that they originally wanted to make a beautiful film about the last of Scotland’s traditional net fishermen. ‘We didn’t realise that we were walking into a war.’

The producer of the film told the newspaper that this is a controversial story with many sides. A lot of people won’t like that the fishermen try to shoot seals raiding their nets, yet the fishermen say that the seals are wiping out the salmon. Activists want to save the seals and the anglers want more salmon for themselves, yet the fishermen want to protect their livelihood and so the battle lines are drawn.

The producer, Andy Mr Heathcote, said that the nets-men have been vilified for years, but their voice has been largely unheard.

The director of the film festival, who introduced the film, said that the audience may have divided views on the rights and wrongs of both sides but that the film may change their view. Certainly, we did not think the members of the environmental group, Sea Shepherd, elicit any sympathy for their cause. In the end, we felt that the audience were more sympathetic towards the nets-men, whose livelihoods were brought to an end by the angling interests. The film ended by highlighting that whilst the nets-men could no longer catch and kill wild salmon, the anglers continue to do so. The final scene was of the nets-men calling Marine Scotland to try to ascertain why netting was being banned. They continue to argue that they were not stopped on conservation grounds.

The film is a timely reminder of what might happen to salmon farming.

A clip from the film can be seen at: http://www.trufflepigfilms.com/fishandfoe/

Surviving or not: Inland Fisheries Ireland recently hosted a group of international scientists to discuss salmon migration as part of the International Year of the Salmon. Leading salmon scientists from Denmark, Spain, Sweden, England and Ireland met to discuss the latest findings of the international SMOLTRACK project.

SMOLTTRACK, funded by NASCO and the EU, aims to determine the survival of young salmon as they migrate from rivers into the sea. Early results have shown that survival is lower than expected, possibly three time lower than in a good year. The scientists did not anticipate that survival would be so poor. Rather surprisingly, SMOLTTRACK does not appear to include any scientists from Scotland.

The Press & Journal recently reported that new research from the River Dee on Scotland’s east coast showed that 48% of juvenile fish died on the way to sea, primarily as a consequence of the activities of a growing population of non-native predatory birds. The Director of the River Dee told the paper that there is a deep concern about the dramatic decline of one of Scotland’s most iconic species.

The Atlantic Salmon Trust’s £1 million Missing Salmon Project aims to track salmon out into the Moray Firth, much farther than ever before, yet the Moray Forth only represents a small part of salmon’s long migration, The Missing Salmon Project will not address what happens to salmon once they are out at sea. The Atlantic Salmon Trust say that mortality at sea is something fisheries manager must bear as a general overhead over which they have no control. However, if the majority of salmon die at sea, then surely, there must be an attempt to try to understand why.

Unlike, European scientists whose focus is what happens in freshwater and near to shore, the Vancouver Sun reports that an international team of 21 scientists have recently embarked on an ocean voyage to try to answer the question as to where migrating fish go when they leave their local waters and why are they dying in such large numbers?

The team of biologists, oceanographers and other specialists from five countries will sail across the Pacific Ocean in search of the six species of salmon as well as the prey they eat. They will traverse 6,000 miles over an estimated 345,000 square miles of ocean including the Gulf of Alaska and areas off the coasts of British Columbia and Washington.

Dick Beamish, a long-time salmon researcher from Canada who conceived the expedition and raised the $1 million to fund it told the Vancouver Sun that despite over 100 years of research, most of what they need to know is what they still don’t know. He said that fifty tears ago, five percent of chinook salmon that left the streams returned as adults, now if 1% come back we think it’s a pretty good year. Today, no-body really knows what happens to salmon at sea.

The research ship will tow a variety of plankton nets to sample tiny creatures as well as a midwater trawl to catch fish and other marine life down to 160 feet. The Vancouver Sun will be reporting progress of the expedition throughout its voyage and we shall be watching with interest.

It’s a shame that the Atlantic Salmon Trust are not investing their £1 million plus in a similar venture. We have a feeling that we know what conclusion the Missing Salmon Project will reach.

Frozen out: For many years frozen food was considered to be cheap and of poor quality yet according to the Times newspaper, you’re not the foodie you think you are if you think you are too posh to shop in the freezer aisle. Frozen food has now become cool.

Journalist, Harry Wallop writes that despite some excellent new TV series on Netflix and a raft of new books worth reading, his greatest discovery this year has been soffrito, a mix of diced carrots, onions and celery which forms the base of all good soups, casseroles and ragouts. Waitrose sell sofrito mix at £1.20 for 500g. Harry claims that using this mix in his cooking has been a revelation.

He says that he cannot be alone as sales of frozen food across British supermarkets increased by 3.6% last year. He suggests that this is not much but following on from growth of 6.2% the year before, this represents an extra £581 million spent on frozen food over the last two years. Apparently, no other food category is growing so fast.

One of the drivers of this growth has been realisation amongst younger consumers that frozen foods offers a way of reducing food waste. Iceland, the frozen food retailer is attracting many new customers especially ABC1s also known as the middle class, because of its stance on environmental issues such as food waste and the use of palm oil. Its vegan range has attracted a cult following.

The managing director of Iceland, Richard Walker told the Times that part of the problem with frozen food is that it requires a different approach to shopping because frozen food often needs to be carefully defrosted before use in order to ensure that it is of the best quality.

Frozen foods have for long been advocated as being fresher. Bird’s Eye have always said that their peas go from field to freezer in the space of two and a half hours. Harry Wallop says that fish in particular is likely to be fresher. Richard Walker told him that if you go to Waitrose all the fish is lying on a bed of ice but look at the label and it’ll often say defrosted. Harry suggests that Mr Walker is being unfair to Waitrose as he could only find Madagascan prawns and Maine lobster tails that had been previously frozen. Mr Walker persists and argues that the proportion of fish that has been previously frozen is much higher on Asda, Sainsbury’s and Tesco fish counters or if it doesn’t say defrosted then it will be several days old. Mr Walker says that customers are deluding themselves if they think that the fish is genuinely fresh. For example, tuna steaks from the Maldives might take six days to arrive into the country and then sit on the counter for a couple of days more.

Waitrose defend themselves telling the TImes that wherever they can the fish they sell is fresh and it is frozen only when it is necessary to maintain quality and availability.

Mr Walker says that fish in most circumstances is far fresher when frozen at sea and defrosted properly in a fridge. He says that freezing is nature’s pause button which locks in all the nutrients, the goodness and the freshness.

Harry Wallop says that consumers are catching on to this but that the greatest reason why frozen food is catching on is that the quality has improved enormously. He cites the example of Iceland’s ‘Zuppa di Pesce’, which Jose Pizarro, a chef who runs upmarket Spanish restaurants, says could be served in restaurants and customers wouldn’t even know.

Whilst, the quality of some frozen food might have improved, we, at Callander McDowell are not convinced that such change has reached the fish section. Over the years, higher quality products have appeared in the freezer but then disappeared as they are too expensive for the typical freezer shopper, yet those who could afford to buy them don’t visit the freezer aisle so never see them at all. Most frozen fish is breaded or battered, fish fingers or cakes. The natural fish tends to be cheaply processed and cheap to buy and they tend to taste the same. Even the arrival of upmarket frozen foods which attract the more affluent shopper, such as ice cream, have not yet influenced the overall image of frozen fish. Mr Walker, of Iceland has tried to be more innovative but his products are also failing to reach their target market. Of course, it is not just frozen fish that are failing to attract consumers at retail, as declining consumer demand clearly shows.

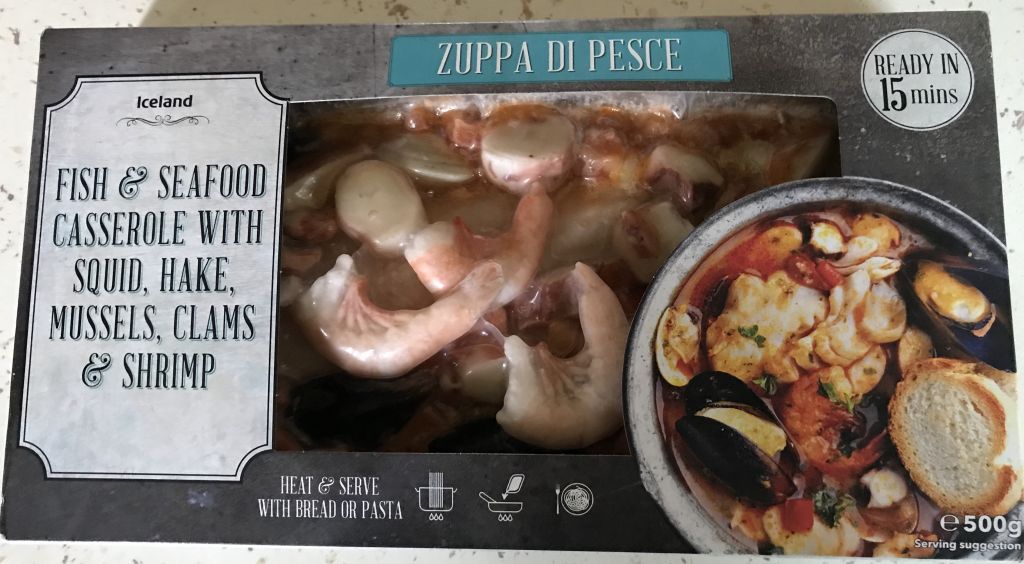

Taste Test: Spanish chef Jose Pizarro’s suggestion that Iceland’s Zuppa di Pesce could be served in restaurants and customers wouldn’t even know, seemed like too much of a challenge for us to ignore. The ‘Zuppa di Pesce’ is actually described by Iceland as ‘Fish and Seafood Casserole with squid, hake, mussels, clams and shrimp’. Not so much soup as stew. The Italian manufactured stew costs £3.50 for 500g so would be considered good value. It comes as a frozen block which is defrosted and cooked through in a frying pan for about 15 minutes. It couldn’t be any simpler.

So, do we think that Zuppe di Pesce is a restaurant quality dish? The simple answer is not in any restaurant we would normally visit. We would know that it is not freshly made.

We have tried some of the other dishes in this range and this is not our favourite. The good bits are the clams and the sauce/soup and possibly the mussels. The rest is only average.

The real problem is that the dish is dominated by squid and unfortunately, the squid is rather rubbery to eat and there is a lot of it. The hake was OK, but our view might have been clouded by the fact we ate a beautiful piece of hake at a Spanish restaurant last week. We also ate some wonderful shell on prawns, but the ones in this soup (still in their shell) were not in any way comparable.

This is a really good innovative way to present seafood. It is very different, yet easy to cook. It’s just this variety doesn’t quite live up to Jose Pizarro’s billing.