Martin’s Blog 3: As we approach the Christmas holidays, Marine Scotland have finally published the minutes of the first meeting of the Aquaculture and Wild Salmon Interactions Group. This meeting took place on 31st October, so it is a puzzle why it took until 20th December for the minutes to be made public, especially as they are so short. The minutes can be accessed at https://www2.gov.scot/Topics/marine/Salmon-Trout-Coarse/salmon

The minutes might be short, but they raise some interesting points. I was specifically drawn to what is described as a list of actions. There are three of these actions that particularly merit discussion, mainly because I don’t understand why they are even on a list, let alone that they require action.

Action 5: JA to summarise evidence for interactions between farmed salmon and wild salmon.

JA is Dr John Armstrong who is listed as being from the Scottish Government but is part of Marine Scotland Science and he has been asked to provide a summary of evidence. This is a puzzle since the Scottish Government’ web page entitled ‘Aquaculture Interactions’ includes a summary of the science. This was only updated in September by Marine Scotland Science, of which John Armstrong is one of the scientists.

The summary of science focuses on sea lice and clearly sea lice are the most contentious of the issues between salmon farming and wild fish but sadly, this summary does not help clarify the issue. This is because, in my opinion, the science presented is highly selective and does not provide a balanced view. Regular readers may remember my two previous blogs which took an in-depth look at two of the scientific papers quoted in the summary and highlighted some major inconsistencies. I am more than happy to have my view corrected, but Dr Armstrong refuses to answer any of my concerns. For example, the summary states that declines in catches of wild salmon have been steeper on the Scottish west coast than anywhere else in Scotland referencing a paper by Vøllestad and others from 2009. However, as I have pointed out previously, this paper does not show this at all. Its use of data is extremely selective and is misleading. I should mention that one of the authors is in fact Dr Armstrong.

Whilst there is a great deal in the summary to be troubled about, my biggest concern, however, is the failure to mention anything about over-dispersion or aggregation, as it is better known. This is how parasites such as sea lice are distributed in the natural environment. A simple explanation is that a few hosts carry many parasites whereas most hosts carry no or very few parasites. This means that when young sea trout are sampled in the wild, a small number of fish are found with huge numbers of lice. Where the problem lies is that the non-scientific audience believe that such samples are representative of the whole population. Unfortunately, the summary of science not only fails to correct this misconception but doesn’t even mention it.

This failure to address this issue would be more understandable if Marine Scotland Science were completely ignorant of aggregated distribution – perhaps fish biologists might not know of parasite distributions – but the issue was discussed in a paper that is available through the Scottish Government website. Carey Cunningham, from the Fisheries Research Services, now Marine Scotland Science, wrote a review of the research of lice infestations on wild salmon and their proximity to salmon farms as an internal report (no 12) in 2006.

The paper states:

‘The overdispersion of lice on hosts creates serious difficulties in interpreting data, particularly that from wild fish. In an over-dispersed distribution, most of the lice are on a few fish with very high loads. This makes obtaining a representative sample difficult, making estimates of mean abundance and intensity unreliable. The population effects of lice loads may be insensitive to the mean intensity; impact may instead depend on the proportions of host that have lice loads above a certain intensity. This proportion cannot be calculated from mean loads, unless the distribution of loads is also known, and this is not often reported. The existence of over-dispersion may be inferred if variance in intensity of infestation exceeds the mean.’

The significance of this statement is that most of the data presented in the scientific literature that involves sampling fish in the wild cannot be trusted. This is why the summary of science is so fundamentally flawed.

The second action point that merits consideration is:

Action 6: JA to scope work required to review threshold levels of sea lice on smolts in terms of causing significant damage.

Wild fish campaigner Corin Smith recently appeared on an audio podcast posted by the Pace Brothers http://paceproductionsuk.libsyn.com/96-corin-smith-salmon-farming-economics-ethical-treatment-of-fish-industry-practises-rspca-assured?tdest_id=445798 . Whilst being interviewed, Mr Smith distinguished between the lifecycles of salmon and sea trout and their relationship with salmon farming. He made the point that when salmon smolts migrate out to sea they do not linger in sea lochs at all and thus spend very little time in proximity to salmon farms. Writing in Trout and Salmon magazine Andrew Graham Stewart of Salmon & Trout Conservation made exactly the same point. Thus, the likelihood of wild smolts being infected with sea lice from salmon farms is minimal.

Despite claims made about the threat to wild salmon, there is little evidence that wild salmon stocks are in decline due to sea lice from salmon farms. As already mentioned, experimental work by the Irish Marine Institute found that mortality of wild salmon from sea lice was about one per cent.

The threshold level often cited as a threat to wild smolts is 12-13 adult lice per smolt. This threshold was determined in the laboratory by Dr Alan Wells in 2006, however the published work considers ‘the physiological effects of simultaneous abrupt seawater entry and sea lice’. This means that this threshold was determined using two different factors in the laboratory. This does not mean that the same effect will be seen in the wild, especially as wild smolts are unlikely to experience abrupt entry into sea water.

A Norwegian study put the level at 10 lice because they could not find any fish with higher lice levels and assumed that this was because they were dead.

In addition, because sea lice are over dispersed in the natural environment, most fish do not carry any lice.

The third action point is the most contentious, at least in my opinion.

Action 7: JA to scope the work required to undertake the comparison of changes in catches of wild salmon between the East and West coasts of Scotland

The reason I feel this to be contentious is that in 2016, John Armstrong co-authored a Marine Scotland Science report looking at the use of catch data to examine the impact of salmon farms on wild fish https://www2.gov.scot/Resource/0051/00515729.pdf

In this report, Dr Armstrong wrote:

“It is very important to note that analyses of fishery catches cannot be used to prove whether or not fish farming has an impact on wild fish as there are many other factors that may cause changes in fish populations and may differ between the regions of coast that were considered. For example, catches of sea trout have declined over recent decades on both farmed and non‐farmed areas in Scotland and it is plausible that different factors are responsible in the two regions.”

Interestingly, Dr Armstrong didn’t publish this report until 2016 which was when I was showing an interest in catch data. He never mentioned his concerns when RAFTS produced their comparison of east and west coast catches in 2011.

Given that Dr Armstrong does not believe that comparison of catch data from different coast can prove salmon farms have an impact on wild fish, it is puzzling that he agreed to scope this work rather than inform the group that such comparisons are not possible. Clearly, I’ll have to wait a couple of months until the next meeting minutes are published to find out.

I also feel this action plan is contentious because as Dr Armstrong well knows, this work has already been done. I carried out this work back in 2016. Some of the many graphs I produced are show in the following image.

At the time I tried to arrange to meet Dr Armstrong to discuss the findings and he refused my request, so we didn’t get to meet until last August by which time my interest in hearing his views about my work had greatly diminished.

When the Interactions Group was first announced, I immediately wrote to the chairman to offer to present my findings to the Group. I recently heard back from him that the Group aren’t interested in hearing from me.

I appreciate that the issues relating to wild salmon – salmon farming interactions are complex and perhaps some of the Group members are not familiar with all the issues so to make it as simple as possible, I would like to look at the catches from just two rivers.

Five years ago, the River Tweed, one of the best salmon rivers in Scotland and the river furthest away from salmon farming reported a total salmon catch of 14,794 salmon and grilse. According to the Tweedbeats website, the 2018 catch was just 5,580 fish.

Five years ago, the salmon and grilse catch from the west coast River Carron was 130 fish. This year the catch was 243 fish (85 salmon and 158 grilse) For comparison, the catch in 2017 was 89 salmon and 68 grilse.

This year’s total is higher than the 5-year average (179) and the 10-year average (235).

Dr Bob Kindness, the Manager for the River Carron, who tweeted the totals for 2018, also drew attention to the sea trout catch which this year was 101 fish and a further 480 finnock. This compares with 2017 when 92 sea trout were caught together with 476 finnock.

Dr Kindness reports that the sea trout were plump which indicates that they had fed well although they were not large. He had personally observed a third of the sea trout and more than half the finnock and said that 90% had no lice and no sign of past lice damage. The rest had a maximum of 6 lice with no damage. He said that similar observations were made during 2017.

My question is that given the latest catch data, should the Interactions Group rename themselves as the East Coast Action group and investigate why catches have declined along that coast so quickly. After all, wild fish catches appear to be doing well in the River Carron despite its proximity to one of the largest Aquaculture hubs on Scotland’s west coast.

REC Review: Whilst most people will focus on the conclusions drawn by the REC Committee in their report on salmon farming, the report discusses the various issues by looking at the evidence given either in Committee or by written submission. There were many submissions made to the Committee, so we would like to explore the evidence selected and see if we can arrive at similar conclusions.

The report is extremely long and covers several different issues, so we will focus on just one – the Interactions between wild and farmed fish and especially the links between salmon farming and the decline of wild fish numbers. This section begins on page 78 of the report.

Paragraph 314: This section begins by stating the importance of the angling sector to the Scottish economy quoting figures produced during a 2017 analysis of the value of wild fisheries in Scotland. This report, by consultants PACEC, estimated angler expenditure of £135 million with an industry of 4,300 full time equivalent jobs.

We, at Callander McDowell believe that inclusion of these figures in this report is extremely misleading as it suggests that the value of salmon fishing to Scotland is much greater than it really is. In addition, the REC report concerns salmon farming and thus only the implications for angling within the west coast ‘Aquaculture Zone’ are relevant.

The PACEC report looked at all wild fisheries in Scotland including netting and angling for coarse fish. The report does not provide figures for salmon and sea trout, nor does it provide a breakdown for the different areas of Scotland.

In 2004, the Scottish Government commissioned Glasgow Caledonian University to conduct a similar survey but this did provide values for salmon and sea trout and for different Scottish regions. The total expenditure on salmon and sea trout fishing in Scotland in 2004 was £73 million, half of which came from Highland rivers. Unfortunately, the Highlands region also includes rivers outside the ‘Aquaculture Zone’ so the total expenditure in salmon farming areas cannot be determined from this analysis. What is known is that typically, 10% of the total Scottish catch can be attributed to rivers in the ‘Aquaculture Zone’, therefore it would be a reasonable to suggest that a similar ratio applied to the value, giving an expenditure of about £7 million per annum.

Critics of the salmon farming industry might suggest that this figure would be greater if salmon farming wasn’t present, with specific reference to the decline of the Loch Maree sea trout fishery. However, as we have regularly pointed out, sea trout catches were in decline long before the arrival of salmon farming to the west coast.

It could therefore be suggested that the REC report gives the impression that angling is much more important to the west coast ‘Aquaculture Zone’ than it really is. That’s not to say that angling should not be able to thrive alongside salmon farming, it is simply that the scale of the angling should be put into some form of perspective.

Paragraph 315: The Committee point out that it was concerns about the impact on wild fish from salmon farms expressed in Petition PE1598 which led to the enquiry. However, as we have indicated previously the Petition was extremely short on evidence. Their main claim was that all the fishery districts in the ‘Aquaculture Zone’ were classified as Grade 3 and this could only be due to the impact of salmon farming. Yet, for 2019, a third of the rivers and fishery districts have been classified as Grade 1 and therefore available to be fully exploited. These improved classifications make a mockery of the claims made in the Petition and lead to the question as to whether the enquiry should have ever taken place.

Paragraph 317: The report states that Salmon & Trout Conservation had commissioned the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research to look at the issue. This is misleading because the report produced by two of NINA’s researchers is simply an edited version of an existing report. S&TC sought advice from NINA because they are of a similar mind. NINA are not exactly impartial on the issue of salmon farming.

Most of the content of the NINA report rehashes their existing work, however one point they make is that according to their calculations, about 50,000 wild salmon fail to reach maturity in Norwegian rivers due to salmon farming. On the same basis the figure would be about 7,000 salmon. This means that according to NINA a total 7,000 smolts might die during their migration and thus fail to reach adulthood. This is due to the presence of salmon farms.

To put this into perspective, a study of the smolt run in the River Spey found that the output ranged between 600,000 and 1.6 million smolts. The loss of just 7,000 smolts due to salmon farming is insignificant compared to these smolt runs even if the figure is correct, which is unlikely. It is also worth remembering that in a typical year, anglers kill more wild fish for sport than this estimated figure. Clearly, their concerns about protecting salmon don’t extend to their own activities.

Guy Linley Adams of Salmon & Trout Conservation told the Committee that there is significant evidence of a pervasive and general impact of sea lice from salmon farms on wild salmonid populations even though S&TC failed to provide a single shred of evidence to support their claims. Instead, it was all circumstantial. Mr Linley-Adams also told the Committee that he was concerned about the focus on sea lice because there are other diseases that affect farmed salmon even though there is not much evidence that such diseases might impact on wild salmonid populations.

Such pronouncements are typical of the S&TC as they clearly want to create as much concern as possible about salmon farming in their crusade against the industry. The problem with S&TC is that their claims lack scientific credibility. Their Scottish section appears to be staffed by an ex-music promoter and a solicitor, yet they readily dismiss any rebuttals from those with a scientific background in fish biology. It’s not surprising that they refuse requests to meet to discuss the issues.

As to the question of the threat to wild fish from other diseases, in Paragraph 332, Professor James Bron argued that the potential to introduce disease to the wild population is low. This point was reiterated by the salmon farming industry in paragraph 331 who told the Committee that they do not experience transfer of diseases between pens, so it would be even more difficult to transfer to wild fish especially with so few fish relatively in such a large sea.

Paragraph 318: We recently discussed the submission from SumOfUS on behalf of 32,762 members. The Committee failed to appreciate that this is a US based organisation whose purpose it is to raise complaints against anything they consider to be big business. This submission was not an expression of concern by local, let alone Scottish people.

Paragraph 320: This discusses one of the most interesting submissions to the REC Committee as it brings into question the diligence with which the Committee reviewed the evidence supplied. The Committee say that there were concerns about the reduction in wild salmon stocks are having on local businesses and the local economy. They draw attention to the evidence submitted by Alan Macdonald of Doonside Fishing’s who told the Committee that sea lice were to blame for the closure of the beat he owns on the River Don. He believes that this is”…due to almost extinction of wild salmon undoubtedly caused by sea lice infestation all along the west coast” and that the closure “has cost one gillie’s job and over 500 bed nights, meals were lost to the local Ayrshire economy”.

It may be argued that we are not part of the wild fish sector so don’t know everything there is to know about wild fisheries, but we are sure that we would have heard if west coast salmon were near extinction. Trout & Salmon magazine reported earlier this year that Andrew Graham Stewart of Salmon & Trout Conservation went salmon fishing on the River Ewe. We are sure that he wouldn’t have bothered if he thought that there was nothing to catch. The comments made by Mr Macdonald are simply exaggerating the fact that wild fish populations are in decline along the west coast and some have been for many years. Wild fish stocks on the east coast are also in decline and those declines cannot be blamed on salmon farming. Seemingly, the wild fish sector appears unable to accept that the declines across Scotland could be all for the same reason.

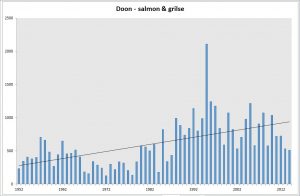

Mr Macdonald said that he closed his beat because of the extinction of wild fish along the west coast but this extinction doesn’t seem to have reached the River Doon. Catch returns for sale and grilse for the whole river are displayed in the following graph. Catches may have dropped in the past couple of years, but so have catches across Scotland.

The official catch data simply does not support his claims. We also note that Mr Macdonald said that sea lice are the problem, yet he did not provide any evidence at all to underline his claims. He is simply repeating unproven claims he has heard from elsewhere.

Paragraph 329: Marine Scotland told the ECCLR Committee about their research to date saying it is not yet possible to quantify the impacts of sea lice on wild fish. It is now unlikely that they ever will since the results of their three-year £600,000 project looking at these impacts was a complete failure. We have heard rumours that the ten-year programme looking at this issue in more depth has now been cancelled. However, the REC Report does say that the knowledge of distributions of fish and sea lice is steadily increasing. We are not sure if the use of the word steadily should have been replaced by selectively instead.

This is because as Professor James Bron pointed out to the Committee (Paragraph 332) in areas without salmon farming, wild fish can get very high numbers of sea lice and it is normal to have 70 to 100 per cent prevalence. This is not unusual because as we discussed earlier, sea lice like all other parasites exhibit an aggregated distribution.

We will end this review with a reminder from Professor Paul Tett from SAMS, who told the Committee that:

‘We could not find definitive evidence in Scotland that sea lice from farmed salmon are having an impact on wild salmon populations… ‘

Perhaps he should tell Marine Scotland Science too!