Loch Maree: After several quiet months, the issue of Loch Maree has been resurrected by opponents of the salmon farming industry. A discussion about Loch Maree featured in an interview with Corin Smith by the Pace Brothers. These brothers are film-makers who were commissioned by Salmon & Trout Conservation to make their video of Loch Maree. As well as filmmaking, the brothers also produce a regular podcast on issues of fishing, hunting and shooting and the great outdoors. These podcasts are typically somewhat lengthy, the one with Corin Smith being well over two hours long. (A link is provided at the end of this commentary).

At around 90 minutes into the podcast, the brothers turn their attention to Loch Maree. Mr Smith then relates:

“The story about Loch Maree is about sea trout. It is all about sea trout. So, Loch Maree used to be a very, very famous sea trout fishery, a recreational sea trout fishery, that was famous the world over. It was the cradle of sea trout fishing and you had lots of people going to stay in the local hotel from the late 1800s all the way through the 1900s. You had a hotel there and three or four different estates with lodges and things and you had about twenty boats on the system, fishing recreationally for sea trout.

A big strong run of wild sea trout probably in the order of 10,000 to 20,000, maybe even more, 30,000, 40,000 50,000 sea trout coming into the Loch Maree system.

And you also have salmon, but the wild salmon story is more about the River Ewe which is the river that runs out of Loch Maree

So, the impact that salmon farming had in terms of a time line there was the first salmon farming operation started up in the mouth of the River Ewe about a mile from the freshwater. It started up in about 1987 – I think that was when the site kicked off and you can see by looking at catch returns which are a proxy for wild fish population numbers that…”

(There then follows a discussion about catch data).

“…virtually overnight, within a couple of years, the sea trout catches on Loch Maree just disappeared, dropped dramatically from over the course of a season probably 1500, perhaps peaking at 2,500 fish with an average of 900 then dropping down to 20 or 30 fish for the year and for today, the numbers are to all intents and purposes virtually zero.

There was a very dramatic reduction in sea trout population which correlated very strongly with salmon farming.”

We, at Callander McDowell, struggle to see a very strong correlation between salmon farming and a reduction in sea trout catches, not just in Loch Maree, but across the whole Aquaculture Zone. On his Facebook page, Mr Smith says that about eighteen months ago he was asked to produce a short presentation for a selection of MSPs about the potential of restoring wild fisheries in the Aquaculture Zone. Mr Smith appears to have used Loch Maree to highlight his view that the economic benefits of restoring wild fisheries to the west coast would outweigh the benefits of salmon farming, something we may consider another time. Including in his presentation was a copy of the graph used in Salmon & Trout Conservation’s report on the collapse of the Loch Maree sea trout fishery which they had commissioned from retired government fisheries scientist, Andy Walker.

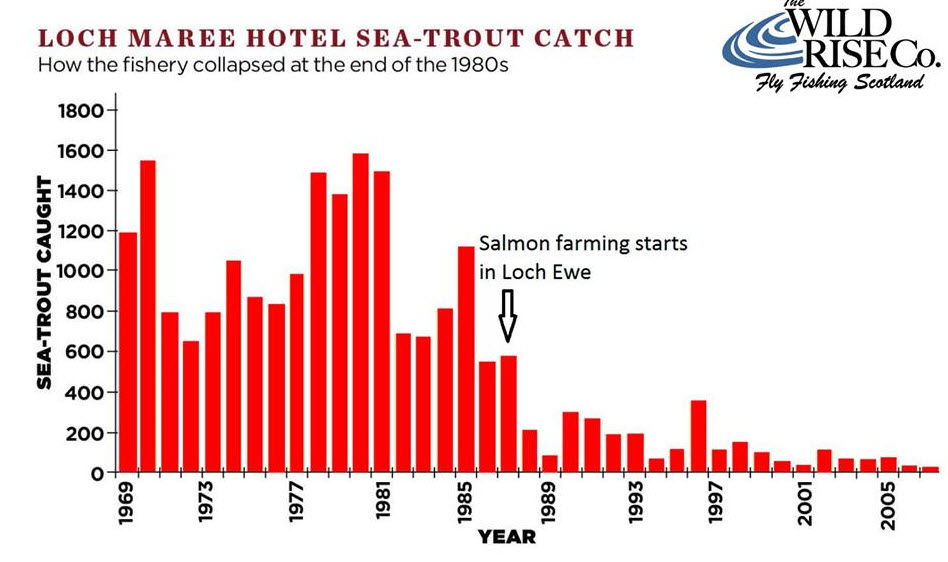

The graph is a bar chart showing sea trout catches from the part of the loch belonging to the Loch Maree hotel. Mr Smith has helpfully identified the year that salmon farming began in Loch Maree.

It is worth pointing out that Mr Smith is incorrect with his assertion that the first salmon farming operation began in Loch Ewe in 1987, a mile from the river mouth. In his report Dr Walker repeats the information that was included in his 2006 paper. This states that:

“In 1987 two commercial marine cage sites were established in Loch Ewe, 4 and 7 km from the river mouth. Both have been in production annually with maximum consented biomasses of 919 and 950 tonnes, respectively. Other than these sites the nearest active marine farms were 40 km by sea to the north in Little Loch Broom and 55 km to the south in Loch Torridon.”

Even this information might be incorrect. To the best of our knowledge, the site near Aultbea had already been in use before 1987 by a different company., who had been growing trout, not salmon.

Returning to Mr Smith’s graph. anyone looking hard enough would be able to see that the catches before 1987 do appear to have a base line much higher than those after 1987. It does look as if something happened in 1987 to affect sea trout catches.

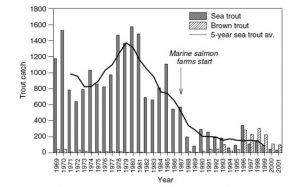

However, when we first saw this graph, it looked rather different. It first appeared in a scientific paper in 2006 that Andy Walker had published with James Butler. We have copied the graph from the paper and it can be seen that the main difference is the inclusion of a five-year average. This measure is widely used in wild catch fisheries as it evens out the peaks and troughs that can occur from year to year.

What is immediately apparent is that the five-year average peaks in 1979 and then starts a rapid decline. By 1987, when the farm was established, the five-year average was already showing a significant decline. From this graph, any correlation between salmon farming and a decline in sea trout catches looks hard to justify. We have tried to discuss this decline with the wild fish sector, but no-one has been able to provide us with an explanation. The five-year average line is a major inconvenience to those claiming salmon farming is to blame for the declines, so the simplest solution has been to remove it from the graph.

However, it is not just the five-year average that is missing, so is some of the data. The Scottish Government have been collecting catch data since 1952 and this is freely available, yet this graph only starts in 1969. There is an additional seventeen years of data that could be displayed and might help present a more informed picture of the fishery and its collapse. In terms of the Loch Maree Hotel, catches have been recorded in the hotel’s catch book for many years. The catch data for many other years could have been presented to identify the trends over a much longer period of time than shown here.

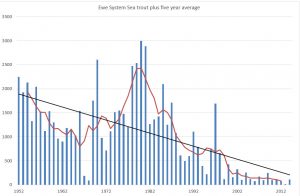

The sea trout catch data for the whole Ewe System, not just the Loch Maree Hotel is presented in the following graph from 1952 onwards. The graph also includes a five-year average and a trendline.

The first thing that is apparent is that the reason for stopping the other graph at 1969 is that the two years prior to that show a complete collapse of catches. Before that, catches were clearly in decline but then managed to pick up during the 1970’s and 1980’s. However, what is clear, is that sea trout catches were well in decline before the salmon farm was established.

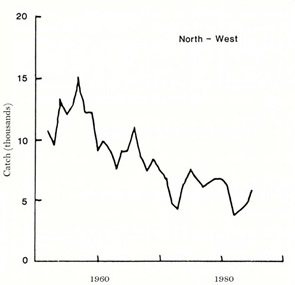

The increased catches during the 1970s and 1980s appear unique to Loch Maree. Elsewhere across the west coast, sea trout catches have been in decline at least since the 1950s. Researcher MJ Picken wrote a paper that was published in 1987, the same year as the Loch Ewe farm was established. His graph of north west Highland sea trout catches clearly illustrates this decline.

This was at a time when salmon farming was very much in its infancy and was unlikely to have impacted much on wild fish. The decline far outweighs the impact of the few small farms then in existence. MJ Picken produced a variety of graphs including one for Loch Stack which he thought superior to the fishing in Loch Maree. The graph shows a rapid decline throughout the 1960s and 1970s. A salmon farm only arrived in the locality in 1985, by which time Loch Stack was a shadow of its former self.

For a more detailed analysis of the collapse of the Loch Maree sea trout fishery please read Martin’s book – Loch Maree’s Missing Sea Trout – available from Amazon.

We’ll end this commentary with an observation about the disparity between the way that salmon farming is portrayed and the reality. In his interview, Mr Smith clearly states that after the arrival of salmon farming to Loch Ewe, sea trout catches from Loch Maree ‘dropped down to 20 or 30 fish for the year and for today, the numbers are to all intents and purposes virtually zero.’

Yet according to the catch data collected by the Scottish Government, between 1988 and 2016, (after the salmon farm had been established) anglers managed to catch a total of 6,016 sea trout from the Ewe System including Loch Maree. More importantly, all these fish were retained, the polite way of saying that the fish were killed.

The interview with Corin Smith can be found at: –

Crazy cat woman: Last week, journalist and commentator Carole Cadwalladr wrote about the late- night tweet sent by BBC broadcaster and journalist Andrew Neil that who replied to another comment by saying that ‘Nothing compared to having to deal with mad cat woman from Simpsons, Karol Kodswallop’.

Writing in the Guardian, Carole said that being called a ‘crazy cat woman’ was an attempt to control and shame and that such online abuse is nothing but a tawdry attempt to limit what we say. She says words aren’t cheap, they are free and in this age of social media, they travel far and fast. Words that are intended to wound or damage are tossed off in the blink of an eye, tapped out in a few seconds flat, on a keyboard or a phone and then press send and then are gone. Yet, according to Carole, they are not. They circulate forever, and their impact goes on.

Carole is so right, which is why we, at Callander McDowell, have stopped using social media other than to notify that relAKSation is available. It is impossible to have a proper exchange on platforms such as Twitter. Most responses end up being abusive in one way or another. In the case of salmon farming, it seems that any genuine comment is mocked or criticised. It would seem that, often or not, there is no thought invested in what is being tweeted. It is mostly nasty.

Although we no longer comment on social media, we do sometimes keep an eye on what is happening on Twitter and Facebook. Over recent months we have followed the development of an anti-salmon farming tweeter on Twitter. Initially, it was clear from the few guarded comments that this person was new to Twitter. The only comments were in response to positive news about salmon farming. However, as this person gained Twitter confidence, the comments became more regular with more widespread coverage of the industry. More recently, the Tweets have now extended beyond salmon farming with comments on anything that the person disagrees with including politics. Such is the confidence of what this person now Tweets that they have become abusive and anyone is seen as fair game. We suspect that if faced with any of those who are criticised on Twitter in real life, this person wouldn’t even dare open their mouth.

Our thoughts about social media are prompted by a report on BBC News concerning the recent furore about kelp harvesting. The boss of a firm planning to mechanically harvest kelp said a decision taken by MSPs to ban such operations ‘seemed a bit crazy’.

Douglas MacInnes of Marine Biopolymers Ltd said that the company was overwhelmed by a social media campaign that opposed their plans. He told the BBC that the company consists of scientists and engineers with little experience of social media. He said that people have a right to object, but a lot of the information circulated on social media was incorrect. MSP’s and Green groups voiced concerns that harvesting kelp would have a devastating impact on the marine environment. These concerns were repeated time and again on social media. By the time the matter was discussed in the Scottish Parliament, social media made it sound as if the company planned to drop an atomic bomb.

We are not surprised that the Scottish Parliament voted to ban harvesting of kelp. We presume that they heard only one side of the story. The salmon industry is subjected to such misinformation on an almost daily basis.

Mr MacInnes said that the company had followed the process as required, but they had been since totally disregarded by the way MSP’s had chosen to respond. He said that they had submitted a scoping report but had been denied the chance of producing an environmental impact study or consult with stakeholders on their plans.

We don’t know whether harvesting kelp has an impact or not but it does seem to us that there is a minority who simply don’t want the west coast to include a healthy and thriving community and use social media as a way of imposing their views to get what they want, even if this is at the exclusion of debate but the inclusion of abuse of anyone who stands in their way.

Commentary: We thought the following article from the latest issue of Fish Farmer merited wider circulation, so we have decided to include it in this issue of reLAKSation.

By Sean Anderson, Marine Harvest – courtesy of Fish Farmer magazine.

Recent media coverage of salmon farming has offered a snapshot of the aquaculture industry and largely portrayed it in a negative light. For those who work as salmon farmers and suppliers to the industry, this media storytelling bears no relation to our day to day reality and the improvements made over recent years to produce top quality salmon, which is in growing demand worldwide.

When I host visitors to my salmon farms, they are often fascinated to learn first-hand about what we do to care for our fish over its three-year lifecycle. It’s this balance that has often gone missing from recent media reports.

Yes, challenges do occur and farmers must overcome them, but there are also important successes, innovations and benefits to the community and human health,

Below are some interesting discussions about my career that I have enjoyed whilst hosting visitors to my salmon farms.

Salmon farming has a much smaller impact on the environment than many media reports would suggest. Far from producing amounts of waste equivalent to large towns, it is important to point out that was form fish is not the same as waste form humans.

It is estimated that organic waste from salmon farming accounts for less that five per cent of the total organic matter reaching the sea from land. It is also estimated that, in 2016, Scotland’s 6.8 million sheep excreted about twice as much nitrogenous waste as farmed salmon, while producing only a quarter as much food.

Salmon farming also remains one of the most efficient protein production systems, benefitting form CO2 emissions one-tenth of beef.

Far from being an environmental risk, producing farmed fish in the oceans is a significant part of the solution to the pressures placed on our limited lands that are available for farming.

According to the National Farmers Union, about 80 per cent of Scotland’s land mass is used for agricultural production, which is the ‘single biggest determinant of the landscape’.

Scotland is known around the world for its stunning beauty, attracting millions of visitors each year. Its agriculture is and should be celebrated. But in comparison, aquaculture uses the sea to grow fish in their natural environment, providing around 40 per cent of the country’s food export value while using less that 0.02 per cent of Scotland’s available coastline.

With aquaculture taking up so little space to grow such a large proportion of the world’s protein, many people will never have seen a salmon farm – which is both good and bad. Good that it highlights aquaculture’s very efficient food production model, but bad that most people’s understanding of the industry is largely left to new outlets to communicate, and not first-hand experience.

Negative media coverage gives the impression of ailing fish and poor growing conditions, whereas we salmon farmers know that is far from the reality.

We know that it makes no commercial sense to neglect the welfare of our fish and to employ anything but the best husbandry techniques. Healthy, tasty top-quality salmon is in huge demand by consumers.

Salmon grow best in clean unpolluted waters, so it only makes sense for us to keep the environment we work in as untouched as possible. Negligent practices lead to poor quality fish, which would soon be rejected by our customers.

Land based recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS) are often referred to as a wholesale replacement for farming fish in the sea.

However, our decades of experience investing in these systems to grow our salmon in its freshwater phase (to about 150 grams) has shown that much more work needs to be done before it could be considered a viable alternative for growing salmon to market size.

As an example, over the last five years at Marine Harvest Scotland, we have spent £47 million growing smolts from eggs in our RAS hatcheries. To produce, 160,000 tonnes of market sized salmon using the same systems would cost the Scottish industry £4.7 billion, resulting in farm raised salmon, which is currently considered a reasonably priced and healthy source of protein, rocketing in price at the supermarket.

The sheer size of the premises required to grow fish on land is also one of the main issues. For example, our new freshwater hatchery in Glenmoriston is the size of two football pitches and produces 800 tonnes of fish per cycle.

For Scotland, just to keep up with current demand, the industry would need 200 buildings of similar size to our hatchery.

For ease of transporting fish to the market, these would be moved to the Central Belt or even further south, probably to industrial estates where planning permission was not an issue, wiping out hundreds of well-paid jobs salmon farming provides across the Highlands and Islands.

Whereas we utilise the ocean’s natural tidal power to flow oxygen-rich water over a salmon’s gills, land -based systems would require power hungry buildings requiring energy to pump, heat, cool and treat incoming and outgoing water.

My farms are certified to the RSPCA welfare standards, which are very strict about providing a comfortable environment for our fish. In order to make land-based farm economically comparable, densities of fish would be up to 10 times higher than what we carry in a sea pen.

Our salmon are grown in pens which are 1.5 per cent fish and 98.5 per cent water.

Recently quoted figures also give the impression that the higher levels of mortality experienced over the past year are commonplace and an accepted part of salmon farming. This is definitely not the case.

At Marine Harvest, 65 per cent of the overall mortality at our farms in 2017 occurred at only 10 of our 49 sites and we are working hard to rectify this.

Last year was particularly challenging but this has certainly not been the norm in the salmon farming industry – unlike the dairy and beef industries, where an average of 25-30 per cent of cattle in the UK dairy herds are removed annually due to illness, and the Scottish upland sheep farming industry, where between 25-50 per cent of lambs expected by pregnant ewes are lost to unexplained causes every year.

As I write this, our farms are experiencing the best fish survival we’ve seen in five years and our sea lice levels are the lowest they have been in over 12 years. This is very good news – but unfortunately not the kind of news that would be shard at six o’clock.

All in all, the issues face by the salmon farming industry are complex, but the situation is far more positive than much of the media coverage we attract would suggest.

At Marine Harvest, we regularly host visits to our farms from people who tell us they are astonished at how the reality differs from what they have heard from our critics.

This would suggest we need to be ever more transparent and actively encourage people to visit our farms to see our successes for themselves.