No debate (a commentary from Dr Martin Jaffa): What does it take to engage in open rational debate about the issue regarding possible impacts of salmon farming on wild fish? A war of words is being conducted through the media because of a seeming reluctance to engage face to face.

This week, the Herald newspaper published a letter from Andrew Graham Stewart of Salmon & Trout Conservation accusing me of a cynical manipulation of statistics to further my thesis that salmon farming causes no significant damage to stocks of wild salmon and sea trout.

This apparent cynical manipulation of the statistics is to repeat the summary of advice given in the ICES report from 6th May 2016. This was produced in response to a request from NASCO to provide up to date information on the possible effects of sea lice on wild salmon populations. The summary states that marine mortality rates for salmon are often at or above 95% and that one view of the additional mortality attributable to lice is estimated at around 1% or one fish in a hundred. I have no idea as to why repeating this information is regarded as a cynical manipulation of statistics other than it doesn’t fit in with Mr Graham Stewart’s view of the salmon farming industry. I can only assume that if I am cynically manipulating the statistics then so are the twenty or so scientists who attended the ICES workshop and who put their name to the report.

Mr Graham Stewart provides his own interpretation of the possible damage caused by salmon farms. He says that “In order to reduce the population from five per cent returning to three per cent returning (as adults following their marine migrations), the lice must be killing 40 per cent of the smolts. The remaining 60 per cent are then reduced by 95 per cent by other factors, giving a three per cent return rate.”

The ICES report does say that there is a second view to the mortality of salmon due to sea lice which is there is a ‘0.6% to 39% reduction in adult returns to rivers’. In fact, the mortality level is the same for both interpretations and it is just the way in which the mortality is expressed as a percentage that is different.

As can be seen from above, Mr Graham Stewart does explain his calculation of mortality but it is difficult to follow. He begins saying that in order to reduce the population from five to three percent of fish returning, the lice must be killing 40% of the smolts but he doesn’t explain why the population has to be reduced from five to three percent.

The 39% (40%) reduction in adult returns is the difference between the number of treated (against sea lice infestation) compared to untreated fish returned. This is not the same as making the assumption that lice are killing 40% of smolts because clearly, they are not. If they were, then there would be a 40% difference in the survival of salmon between the two groups. In fact, the data shows that the difference in mortality between the groups is less than one percent.

Mr Graham Stewart assumes that 40% of the smolts die leaving 60% which he then applies the 95% general mortality. He is wrong. The 95% mortality applies to all salmon populations, regardless of whether they migrate from rivers with salmon farms or rivers without. Ninety-five percent of all migrating salmon smolts die at sea. Salmon farms have no influence on that mortality. If salmon farming killed 40% of smolts then the total mortality would be 135% which makes no sense. However, applying 95% mortality to the supposed 60% remaining smolts also makes no sense because whilst it gives a three percent return, it is a different three percent return to the 40% reduction applied to the surviving five fish that do return to the river. This means that 3% of fish return following mortality by sea lice and another 3% return following the more general at sea mortality. Therefore, according to Mr Graham Stewart, 6% of fish return after being exposed to salmon farms but only 5% return when salmon farms are not present. Whether Mr Graham Stewart feels that I have cynically manipulated data or not does not detract from the fact that the vast majority of migrating salmon smolts die from causes other than sea lice. I would be happy to discuss these numbers with him but he has repeatedly rebuffed any of my attempts to meet him.

It is a shame that Mr Graham Stewart prefers to focus his ire on a study which has already been thoroughly discussed. Instead, I would welcome his input in helping understand why there is such a difference in the number of sea trout caught from the Rivers Ewe and Polla even though both rivers are in close proximity to salmon farms. According to perceived wisdom, both rivers should have lost their sea trout populations but last year, the River Polla produced three times the normal catch including a fish weighing 10lb. So far, I have not received any explanation as to why sea trout catches from the River Polla have been so good.

This week, I was guest speaker at the Institute of Aquaculture at the University of Stirling. My presentation on the interactions between salmon farming and wild fish provoked some interesting questions and a lively debate. The audience, of course, had an interest in aquaculture but most of the questions related to the impacts on the wild fish. The meeting could have been even more interesting had the audience included people from the wild fish sector, especially since the interactions between aquaculture and wild fish are such a hotly discussed issue as demonstrated by Mr Graham Stewart’s comments.

Such an audience of people with an interest in the wild fish sector will be gathering in Scotland in the coming weeks. The Scottish Salmon Festival, which according to Fishupdate.com seeks to champion all aspects of Scottish salmon, will include a scientific conference organised by the Rivers & Lochs Institute of the University of Highlands & Islands. One of the presentations in the programme is ‘salmon farming – minimising the interactions’ so another presentation about what interactions exist would seem to be a close fit. However, when my name was put forward as a potential speaker, Professor Eric Verspoor replied:

“The purpose of the conference is not to debate issues, as it is in the case of many others, but to educate and inform the targeted audience on the latest science developments in the area of science focus.”

I may be getting a bit long in the tooth but in my day, universities and conferences were exactly about debate and exchanging ideas. It isn’t necessary to have a conference to educate. In fact, The University of Stirling informed me that details of my presentation this week received over 1000 hits through the Institute’s Facebook page (and that is whilst most students and staff are on vacation).

It has crossed my mind and this is purely my opinion that is it being suggested that there is a difference in perception between my presentation which may be seen as debateable and all the other presentations in the conference which perhaps are perceived by the organisers as being of unquestionable fact. If this is the case, then why does the conference programme include time for discussion? Is this not the same as debate?

I have written more than once that those from within the wild fish sector only get to hear one set of views because the angling press refuses outright to print the opinion from anyone connected to the salmon farming industry. It is shame that this celebration of Scottish Salmon is simply following this pattern. In my opinion, the Scottish Salmon Festival is a real opportunity to open up the debate so that both wild fish and aquaculture can learn to live and work together in harmony. It already happens in much of the west coast, it is just that there are some who still have not got the message.

In his letter in the Herald, Mr Graham Stewart writes that my views have no credibility. Instead, he says that there is an overwhelming acceptance by eminent fishery scientists that salmon farming is responsible for a significant sea-lice induced reduction in marine survival. Mr Graham Stewart doesn’t name these eminent fishery scientists but if they are so eminent then they might also be sufficiently open-minded to hear a different view to their own.

Ninety five out of every hundred wild salmon smolts die at sea. This is the real threat to wild salmon yet, whilst the spotlight is focused on the salmon farming industry, these ninety-five out of every hundred fish will continue to die.

In the pink: BBC News report that a scientist has raised concerns about what is believed to be a non-native salmon species being caught in the Scottish Highlands. This is because angers have reported catching Pacific pink salmon, also known as humpbacks in the Ness and Helmsdale rivers. Professor Eric Verspoor, director of the Rivers & Lochs Institute at the University of Highlands & Islands told the BBC that DNA tests would confirm if the fish found in the Highlands were humpback salmon. He said that if there is confirmation of the species, they are likely to be stray fish related to pink salmon introduced to rivers in eastern Russia in the mid-1950s.

Unlike Professor Verspoor, the wild salmon sector is already certain that the fish caught are Pacific pink salmon. There are plenty of photos of the fish in circulation and all show the typical characteristics of this species. It is not as if this is the first-time pinks have been caught around the UK coast. We, at Callander McDowell discussed the origins of these fish at least a couple of years ago.

Pink salmon eggs were transported from Pacific Russian rivers to the Kola Peninsula in 1956. The aim was to improve the local fisheries economy. However, it took many such introductions before the fish established a self-reproducing stock. The fish have subsequently established similar stocks in the rivers around the White Sea and in some rivers in Finnmark in Northern Norway. In addition to improved fisheries in the White Sea, it was hoped that the fish would be another target for rod fisheries around the Kola Peninsula to help develop a tourist industry.

Professor Verspoor said that the non-native species could become established in Scotland and compete with native Atlantic salmon. That the fish caught were found running up the rivers is worrying to Professor Verspoor as it suggests a spawning intention. He said that it would be interesting to know whether the fish caught encompass males and females and whether they are reproductively mature or not.

Dr Eva Thorstad of Norwegian Institute of Nature Research (NINA) reported recently that nearly 250 pink salmon were caught from about 50 rivers along the Norwegian coastline over a period of just 11 days. All those that were checked were mature and 46% of them were females.

Dr Thorstad was asked why there have been so many pink salmon caught this year. She replied that it is not known why. She suggests that conditions might have been ideal for breeding last year and hence many more fish in the sea. Dr Thorstad says that these fish naturally spawn a little earlier than native Atlantic salmon but it is only in the past few days that a male salmon with the characteristic hump has been recorded.

The obvious question is whether Pacific pink salmon pose a risk to wild salmon stocks in the UK. The answer is that no-one seems to know. However, the Irish Times reports that Pacific pink salmon have been caught in Galway, Mayo and Donegal rivers. The Irish Independent say that anglers exploit about 15% of native stocks so if the pinks are being caught at a similar rate, there could be many more pinks still in the rivers. The same would therefore also apply to rivers in Scotland. If the fish do become established in Scottish rivers, there will definitely be impacts on the local environment.

As we already mentioned, this is not the first time that pink salmon have been recorded around the UK coastline. Alarm bells should have been ringing after the first sighting given the immense damage that has been caused by some other non-native introductions. We would have thought that the wild salmon sector would have already considered the implications of a pink invasion and what could be done to stop it. Surely, a plan should have already been drawn up, even if it had never been needed. We have no idea as to whether such a plan exists but in all likelihood the wild sector has always considered that farmed salmon are the biggest threat, to the extent that now a real threat exists, it seems to have caught everyone by surprise. Certainly, Pacific pink salmon do not seem to have been included in the Atlantic Salmon Trust’s suspects framework study.

Since it is likely that Pacific pink salmon are now present in Scottish rivers and could in the very near future become a regular fixture in Scottish rivers, perhaps, part of the Scottish Salmon Festival conference programme should be amended to include discussion (or education) about this new Scottish fish.

Under the cosh: Fish and Fly.com recently commissioned an article reviewing the various organisations in the wild fish sector and their efforts to help protect wild salmon. We at Callander McDowell are naturally interested in what the article had to say about Salmon & Trout Conservation Scotland. A request for their latest plan of action was met with no response, something to which we are now quite familiar. The article reports that the organisation did plan to launch an aggressive campaign to restore the sea trout population of Loch Maree but it is suggested that the adversarial approach adopted by S&TC is well -trodden ground and one that others who have been involved in the aquaculture debate are gradually distancing themselves from and instead adopting a more collaborative style approach.

An article this week in the Daily Mail suggests that S&TC Scotland have not yet followed others with a willingness to work with the salmon farming industry. The two page spread tries to detail all that they think is wrong with the salmon farming industry from sea lice to dyed flesh. The hope is that Daily Mail readers will be deterred from buying and eating farmed salmon. However, this is unlikely because if Daily Mail readers followed every supposed scare story about food that the newspaper published, they would now be eating fresh air.

As we have previously suggested, the main victim of this type of campaign will be wild salmon because whilst the focus is aimed at farmed salmon, wild salmon continue to die at sea for reasons unknown.

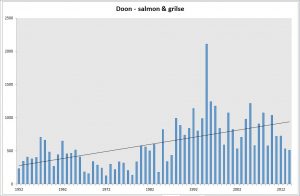

The Daily Mail article covers well-trodden ground which we will not revisit here. We were more interested in the opening paragraphs which relates the story of river proprietor David Cosh. We, have actually discussed Mr Cosh and his river beat in a previous issue of reLAKSation. He has decided to close his fishery because he thinks anglers are not catching enough fish to justify what he charges. He told the Daily Mail that records show that in 1995, 960 fish were caught from his 1.75 mile section of the River Doon in south west Scotland. In 2015, the number had fallen to just 27. Mr Cosh blames salmon farmers further up the coast for the collapse of his fishery.

Whilst in 1995, the number of salmon caught from his fishery was just 27, the number of salmon and grilse caught from the river as a whole was 285 and last year, this increased to 320 fish. Interestingly, whils Mr Cosh says the fishing has collapsed, an examination of the catches from 1952 onwards shows that the River Doon has actually improved, especially in the years following the arrival of salmon farming up the coast.

Mr Cosh looks back to 1995 and rues the days that salmon farming came to Scotland. He says that in 1995, 960 fish were caught form his beat. The records actually show that the river produced 2,111 fish (of which 1,496 were kept and killed). The graph of catches shows that 1995 was an extremely unusual year with catches way above what was considered normal for the river. A catch of 960 fish was never normal on the River Doon and it must be remembered that salmon farms were extremely active by then.

The Daily Mail reports that David Cosh has just returned from a 2,500 mile trip to go fishing for salmon on the Kola Peninsula in north-western Russia. He told the paper that he caught more fish in a week in Russia that was taken from his stretch of the River Doon in a single year. Mr Cosh didn’t say what species of salmon he caught but the Kola Peninsula is exactly where millions upon millions of Pacific pink salmon have been released over the years. Given that these salmon are now turning up in many of Europe’s Atlantic salmon rivers, it might be assumed that the Kola Peninsula is currently awash with many pink salmon and it is these fish that Mr Cosh caught.

It now seems rather ironic that it is salmon farming that is considered a threat to his river.