Less seafood: Intrafish report that young Norwegians are eating less and less seafood. Of most concern must be that consumption of salmon is down. Researchers GFK have found that sales of fresh fish (including salmon) fell by 23% last year. The decline is even greater in the first quarter of this year with fresh fillets dropping by 42%.

Fish consumption in Norway had increased slightly during 2012 and 2013 but consumption has since fallen. The biggest decline is by households aged 34 and under who are eating 46% less fish and seafood. IntraFish say that these declines have caused alarm bells to ring in Norway but we, at Callander McDowell are not surprised. We have been raising such concerns for years but we have been a lone voice. The reality is that these trends are not unique to Norway but are more typical of many countries in the developed world. Fish and seafood is fast disappearing from the menu as the more traditional fish eaters age and pass away.

The view from Norway is that to reverse the trend, it is necessary to improve the availability in stores and ensure that fish is offered in the convenient formats that younger consumers seem to prefer.

There is also a view that there must be more focus on marketing, especially as advertising of fish and seafood appears very low, certainly in comparison to advertising of meat. There is also a view that the emphasis should move away from health and diet towards a focus on everyday food. This is something we have repeatedly argued over the years. Young people aren’t attuned to eating for health but rather they eat what they like and fish isn’t that. Yet, there is still some in Norway of the opinion that healthy eating should take centre stage.

We, at Callander McDowell think that it doesn’t really matter whether it is health or everyday eating that is being promoted as neither will in our view change consumption patterns. There is much more to changing consumption patterns than saying fish is convenient or healthy. There are many more obstacles to overcome than that. It requires a very different mindset and one that is not appealing to those involved in marketing and promotion.

All too often, marketing is aimed at showing those who pay that their money is being well spent. There is a tendency to cozy up to celebrity chefs and become involved in cooking competitions or sponsorship of unrelated events. This is because in marketing terms awareness seems to be more important than getting consumers to eat fish. Just because someone is aware that fish can be healthy is meaningless unless it translates into sales.

Equally, stressing convenience is pointless if new convenient products do not address other concerns. For example, the smell of cooking fish can be a real deterrent for young people.

However, the real issue for fish marketing is that in order to show that sales/consumption is increasing, campaigns are often targeted to persuade those who already eat fish to eat more than trying to get those who never eat fish to eat one portion. This emphasis has meant that young consumers have been ignored and falling consumption is the price that is being paid.

The patterns of fish consumption are changing and in the most simple terms, the fish and seafood industry must change if the decline in fish consumption is to be reversed.

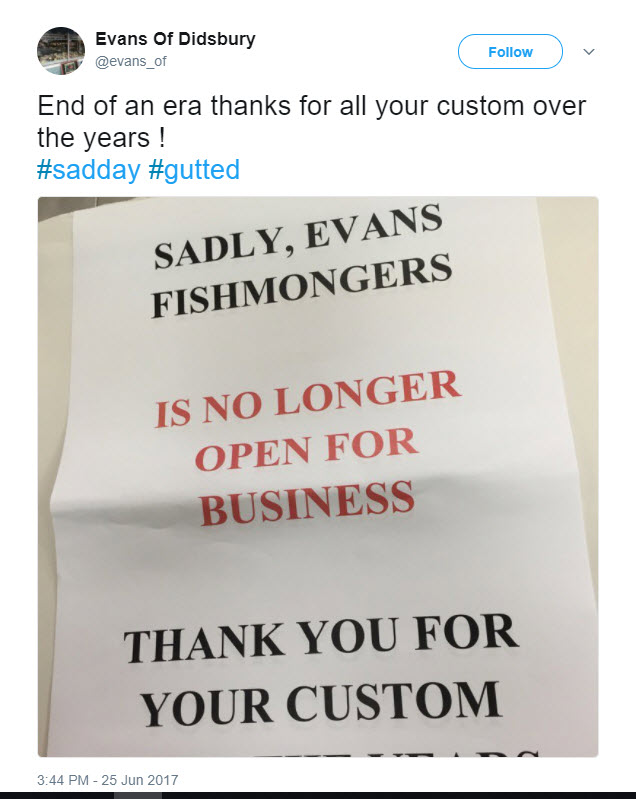

Evans above: Didsbury is an affluent trendy leafy suburb of Manchester. Since 1971, a constant feature at the village crossroads has been Evans the fishmonger, that is until June 25th when the shop closed for good. If an area like Didsbury cannot sustain an independent fishmonger, then there are few places that can.

The closure of Evans the fishmonger is yet further proof of the continuing decline of home fish consumption in the UK.

Manchester is a major city in the UK, yet the number of remaining independent fishmongers can be counted on just a few fingers. A very sad day indeed.

Good fishing: We noticed in the Irish Times that the salmon fishing around Galway is good this year. The newspaper says that there are plenty of salmon to be caught with 211 landed in just two weeks. Tight lines as they say. Of course, they are not the only salmon to be found in Galway!

The right to challenge: Scientific papers can often be taken by some as gospel, being regarded as true and implicitly believed. Not only have these papers being published in print but they are also peer-reviewed, thus whatever these papers reveal must be correct.

Unfortunately, this is not true. Scientific papers, especially those that relate to what happens in the natural world, are simply a contribution to our scientific understanding. That understanding may be correct or equally, it may not. Researchers use scientific papers like a jigsaw, putting the bits together to produce a new picture. The scientific paper often reflects just part of a wider puzzle. For example, take the subject of sea lice. A scientific paper may report that in the laboratory, a young fish of a certain size will succumb if it is infested with ‘x’ number of sea lice. This does not mean that the same fish living in the wild will die if it has the same level of infestation. There are so many other factors in the wild that can influence the mortality of infested fish, that no firm conclusion can be drawn from the paper other than if a fish is infested under the same laboratory conditions, it could die when the lice loading reaches a certain number. However, if this paper is considered along with other research as to the mortality of young fish, then it may eventually be possible to arrive at a conclusion that can be applied to fish in the wild.

Unlike some research, work on sea lice, for example, has a commercial implication. There is plenty of research that is purely academic and remains within the scientific world collecting dust in the library. More applied research has a wider interest that extends far outside the science laboratory. As the research can impact on commercial decisions, it is right that it can and should be challenged. Yet, some scientists seem to take offence when others actively challenge their work. They seem to be offended in much the same way that offence might be taken if it were the gospel that was being challenged.

We, at Callander McDowell, mention this because the journal Morgenbladet has recently published a series of articles which investigated examples where various researchers have come under scrutiny. This was prompted by comments made by Per Sandberg, the Norwegian Minster of Fisheries who said that there are some dark forces of opposition that have existed for a long time. He said that they include politicians, professors, and institutions. He said that they are at universities and in our academia.

Morgenbladet responded suggesting that Norway is a country where seafood is important and that it can be difficult to separate politics and business. They suggest that this relationship can be disrupted by researchers who say that the science does not always support some of the business decisions. The journal interviews several scientists who say that they have fallen foul of business or political interests. We cannot comment on these specific cases but would simply argue that we firmly believe that anyone, whether a highly qualified academic, a business leader or a senior politician should be able to challenge any scientific work, regardless of whether it is in process, peer reviewed or published in the most esteemed journal. At the same time, any scientists should be happy to explain their work and justify their conclusions.

We are reminded of an example, which was challenged from outside the scientific community and subsequently opened up major questions about how the salmon farming industry was being portrayed. This example comes from the work of independent Canadian researcher Vivian Krause and is detailed on her website Fair Questions. Vivian details how she became involved in questions about demarketing of the salmon industry through a complaint against the University of Alberta and the journal Science.

Vivian had read local headlines in British Columbia linking sea lice from salmon farms to high levels of mortality amongst wild pink salmon. The David Suzuki Foundation had said that salmon farming had caused sea lice levels to sky rocket 30,000 times higher than natural. They described the research as undeniable, compelling, irrefutable and proof.

As Vivian had been connected to the salmon industry for a short time, she took an interest in the research and got hold of the actual paper. She writes that contrary to the claims made by David Suzuki Foundation, the research claims were plainly false. When she read the paper, she found that sea lice levels at salmon farms and mortality in the wild were never actually reported. In fact, the data was never even collected so they could never test their hypothesis that salmon farms harm wild salmon. This would have been extremely difficult anyway given that for some of the time of the study, the salmon farm wasn’t even stocked with fish.

Later, the lead researcher of this study admitted to a public hearing of the BC Government that the findings were all correlative – a correlation does not show causality, yet the University of Alberta, where the research was conducted issued a press release claiming that ‘wild salmon mortality caused by fish farms’. When the University was alerted to the concerns, they removed the press release but by then over 500 news stories had reported the research (http://fairquestions.typepad.com/rethink_campaigns/what-got-me-started-uofa-complaint.html ).

Had Vivian Krause not challenged the claims, then this paper would be yet another piece of the scientific jigsaw claiming salmon farming is responsible for killing wild salmon. This challenge to the paper from the University of Alberta led Vivian to look at how the research was funded and subsequent to the identification of a multi-million dollar demarketing campaign aimed at swaying public opinion against farmed salmon, with claims that it damages both human health and the environment.

Although Vivian’s intervention and the subsequent publicity led to the end of this concerted campaign against salmon farming, the consequences continues to this day. Many scientific papers tend to be a mystery to the average person so it is right that they should be challenged and not accepted as Gospel. Researchers should be prepared to make their work accessible especially if it has implications to the business sector, rather than just being of academic interest.

Closed for business: iLAKS have reported that Langsand Laks, a closed containment farm based in Denmark has suffered a ‘sudden and unexplained’ mortality of 250 tonnes of salmon representing the death of between 225,000 to 250,000 fish, its entire stock. Given that there are calls for the salmon industry to move to closed containment, an alleged mortality of salmon in cage farms of under 15% is hardly significant compared to the 100% mortality experienced by this closed containment salmon farm.

Langsands Laks believe that the cause of this wipe out is either due to toxins produced in the plant, the water intake or by criminal acts (sabotage). When we, at Callander McDowell, heard the news of the mortality, our immediate thought was that the cause was a water quality issue. Our view remains the same. The company reported that the fish were not showing any signs of problems such as reduced appetite or elevated mortality which points to a sudden change in the water. We certainly do not believe that the mortality was the cause of deliberate malicious action (unless there was some aggrieved ex-employee we don’t know about).

Closed containment systems rely heavily on complex filtration systems but these can lead to problems in that the technology can be so advanced that there becomes an overreliance on it. This means that often simple routine testing can be ignored.

Equally it is often forgotten that filtration systems are not a magic solution to removal of undesirable wastes. Whatever is added to closed contained systems has to be balanced through the removal of the consequences of the growing system. The presence of a filter doesn’t mean that everything automatically disappears. Instead, it can often rear its ugly head, as Langsland Laks has now found to its cost.

This is why we have always rejected the idea of closed containment. Those who most vocally advocate its wider use usually have never even seen, let alone worked, a closed system.