End of the road: On the 12th of December, the Scottish Government’s Marine Directorate issued a response to the consultation concerning the proposed river gradings for 2026. In the document giving feedback they repeat a statement made in the original consultation. This states:

Why your views matter – Your views inform the process of finalising the river gradings for the 2026 fishing season which are used in the annual amendment to The Conservation of Salmon (Scotland) Regulations 2026.

Except public views don’t matter at all. Marine Directorate go through this consultation process because they have to, but in my opinion, they don’t appear to take a blind bit of notice of what is said. The proposed gradings are much the same as they were before the consultation took place despite some firm views being expressed. This comes as no surprise because my experience is that the scientists in the Marine Directorate are stuck in a very large rut of their own making and consequently to use another colloquial saying, they cannot see the wood for the trees.

At the end of November, I received a response to a note I wrote to the Minister, (which she probably never saw), expressing concern about the measures used to determine the conservation of salmon stocks. In particular, the use of five year’s averages. This year’s conservation gradings include a very good example of this, which is the Rover Morar on Scotland’s west coast.

According to the proposed changes, the River Morar is one of eight stocks whose conservation status has improved compared to the previous year and which no longer require mandatory catch and release. For 2026, the River Morar is classified as a Grade 2 river.

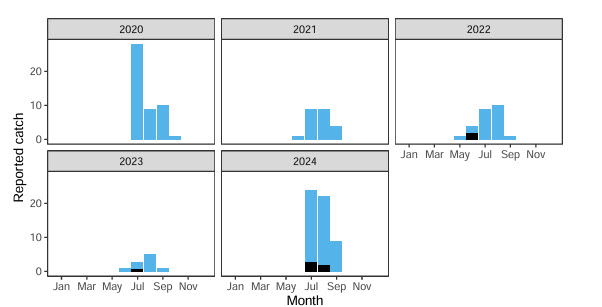

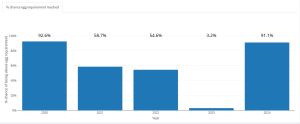

It can be seen from the following graph that the % chance of egg requirement reached has increased by 87.9 percentage points in just one year after three years of decline.

The reason for this change is the changing fortune of the salmon catch, which although not apparent from the graph used by Marine Directorate, were 48, 23, 25, 10 and 55 for the years 2020 to 2024.

The black bars indicate fish which have been killed, despite the mandatory catch and release. In 2022, two salmon were killed with one grilse in 2023 and five grilse in 2024, which suggest that the rules for mandatory catch and release are not working. I would imagine that the explanation of the need to kill these fish was that the fish was badly hooked and the hook could not be removed without damaging the fish.

Even though the 2025 fishing season is over, the catch data for last year is not included because of the archaic collection system still in use. This means that the conservation measures are based on the average of five years data from 2020 to 2024. We already know that 2025 is likely to be the lowest catch on record yet the Marine Directorate is happy to change the status of the small river from mandatory catch and release to one where controlled catch is allowed. It is nonsense that the most recent catch data is not considered in determining the conservation status of any river in Scotland.

In their letter, the Marine Directorate says that the assessments are designed to ensure that they are not unduly influenced by the assessment for a single year either good or bad, which is why the assessments are based on a five-year average.

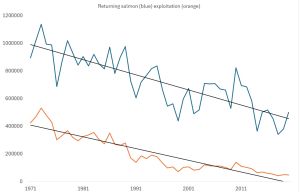

This would be understandable if these conservation assessments had been introduced long ago but as they only came into force in 2016 good news was already consigned to history. Obviously, the Marine Directorate had forgotten to consult the graph of returning salmon against salmon catches, which shows that both returning fish and catches were in decline from as long ago as 1970.

2026 does not seem to be a year that conservation measures should be relaxed, especially when the margins are so small. The total of the percentage eggs reached in the first image of this commentary totals 300.2 giving a five-year average of 60.04 which just falls in the grade 2 category of between 60 and 80% achieved but the margin is very slim. The decision to award this river a grade two classification is highly questionable with just 0.04% over the limit.

Interestingly, one of the issues raised in the consultation but was not mentioned by the Marine Directorate was whether there should be a Grade 2 classification at all since both Grade 1 and 2 allow for the retention of fish. The difference is that Grade 2 rivers should encourage catch and release as opposed to killing the fish, whereas anglers fishing Grade 1 rivers make the choice themselves. The distinction is hardly worth the effort.

In total, the Marine Directorate received 40 responses which is not a great number. Of these 26 respondents agreed for their views to be published.

The one that is of most interest is the one from the River Dee Salmon Fishery Board who plead the case that the River Dee should not be classified as a Grade 1 river and rightly so. A couple of other respondents make a similar claim about other rivers. Their response states:

“In the case of the Dee, it has been classified a Grade 1 under this assessment, despite the population showing a 50% decline since the 1970s and with this decline accelerating in recent years. Whilst the current exploitation is therefore considered safe under this grading system, it does not recognise that anglers on the Dee returned alive 99.3% of catches last year and have returned 98% or more of the catches for the last 15 years. Therefore, the current exploitation is very close to zero, and thus whilst you can conclude that these current levels of exploitation (0.7%) are sustainable, you cannot conclude that the population has no conservation concerns and it does not reflect the very great threats posed to this salmon population which come from many factors, none of which are fisheries exploitation.”

They go onto say:

“As mentioned in previous years’ consultation responses, and acknowledged, the assessment tool is not able to assess separate salmon populations within a river system. For example, it is well accepted that spring salmon populations throughout Scotland are in poor status, including the River Dee, but because the grading is applied to the entire river population, this sub-population is classified as a Grade 1. To exemplify, the spring salmon population on the Dee has seen an 80% decline since the 1970s, compared to the 50% decline overall.”

Clearly, when one of the major salmon fishery boards questions the grading system, the Marine Directorate should do more than consign the view to a response section of a public consultation. The problem is highlighted in the letter to me that:

“The Scottish Government is part of the international consensus of concern for declining stocks of wild salmon across the species’ entire range.”

Of course, just as the Marine Directorate talk about a consensus view on sea lice and salmon farming, is that there will always be a consensus on these issues when the discussion is only with others that share your view. Whilst they say that is an international consensus on methodology, the reality is that wild salmon are in crisis across all their range. Clearly, the fact that there are responses to the consultation, shows that not everyone shares the same view but unfortunately, as with sea lice, the Marine Directorate are unwilling to engage in a proper discussion with the wider public.

I used to have a view that certain measures should be put in place in order to help safeguard wild salmon populations. These include:

- Extending the closed season to include the spring months with the aim of protecting the threatened spring salmon.

- Enforcing mandatory catch and release so no salmon is killed. Any fish which dies as a result of angling should be frozen and retained by the proprietor and handed over to the scientific community for investigation. No fish should die and then find its way to the table.

- For those rivers with low levels of egg production such as the Morar in 2023 (3.2%), the rivers should be closed completely to fishing.

As I said, this is what I used to think. I now have changed my mind. I don’t believe any measure including the banning of all exploitation will make any difference to the decline of wild salmon stocks. They will continue to decline regardless of any measures imposed to control angling. Such measures may postpone the inevitable, but salmon are on the path to local extinction regardless. We may as well let anglers have their sport whilst they can.

The reality is that whatever is affecting salmon is happening out at sea and as the wild fish sector have already decided that finding out what is really at the root of the problem is beyond their capability and therefore they prefer to remain in ignorance, any measures necessary to either halt or even reverse the declines will never be implemented. Therefore, there will only ever be one outcome.

In the reply to my note to the minister, Scottish government officials from the Marine Directorate have written in conclusion that:

“As we have set out in previous correspondence to you, this Government’s Wild Salmon Strategy and its accompanying implementation plan have set out over 60 actions to help protect Scotland’s wild salmon and their habitat. The Plan was published in February 2023 and will run over a five-year period, to 2028, with the vision of having a wild Atlantic salmon population that is flourishing and an example of nature’s recovery.”

We are now three years into the plan and the vision of having a flourishing wild salmon population and an example of nature’s recovery is nothing more than a pipe dream. The Wild Salmon Strategy was doomed from the outset because it has more to do with protecting wild fisheries than the wild fish. We have seen examples of such protection previously, when Marine Directorate scientists wanted to reduce the 109 fishery districts by half, in order to protect the interest of the river proprietors but which would have significantly reduced our knowledge of wild salmon populations. Fortunately, the Information Commissioner applied common sense and reversed the Marine Directorate’s actions. If the Marine Directorate had had its way, we wouldn’t have known that the River Morar salmon and grilse catch was 55 fish in 2025 of which five grilse were killed despite the mandatory catch and release policy. This information would have been amalgamated with the salmon catch from other fishery districts.

Farming: Whilst the Marine Directorate consultation concerned the conservation status of Scotland’s rivers, 40% of respondents (16 people) expressed views demanding action of other pressures that needed to be taken now in order to protect Scotland’s salmon populations. These include:

Issues with river barriers (20%)

Aquaculture (18%)

Predation (18%)

Issues at sea (15%)

Illegal poaching (13%)

Climate change (13%)

Although the numbers of respondents are small, just 18% (3 people) expressed a view that aquaculture needs increased regulation. Of these three only one agreed to have their response published. It is always interesting to read the views of those who attack aquaculture such as that which follows:

“I fish for salmon and so have a keen interest in salmon numbers and conservation measures. I am troubled by the fact that there are more conservation restrictions applied to salmon (rod) fisherman than to the fish farms that cause so much damage to Scotland’s rivers.

We need much more openness about the ecological disaster that is offshore salmon farming. The in-sea fish farms should be shut down. If there is to be fish farming, it should be done in closed containers, on shore, with salt water pumped from the sea to the farms. The wastewater can then be properly treated so that when it returns to the sea, it is clean and not contaminated (mostly with sea lice that kill wild salmon and sea trout, as has been proven scientifically, many times).”

The problem is that the angling fraternity only hear about aquaculture from the angling organisations and never from the farming industry itself. This is because the angling magazines aren’t interested in publishing articles from the salmon farming industry. Trout and Salmon has a new editor and at first, he showed an interest in publishing views from both sides, but he quickly changed his mind. Interestingly, he also didn’t want to publish a commentary about why wild salmon are now in crisis presumably because talk of the prospect of no salmon is not what readers of an angling magazine wants to hear.

Meanwhile, the low response about aquaculture may reflect the view that many anglers, especially those that fish the east coast rivers, now recognise that salmon farming is not the reason why there are so few fish to catch.