Scottish lice: the Scottish Environment Protection Agency sent me a present on Christmas Eve – the list of sea lice sampling on sea trout for 2025. The only way that I could obtain this information was by a FOI request as Fisheries Management Scotland, who manage the list refuse to engage with me because they don’t like what I have to say and the Marine Directorate who previously have overseen the list now say that it has nothing to do with them. It is beyond my understanding why I needed to submit an FOI request for something that should be posted within days of the sampling taking place. After all, it is various claims about sea lice infestation of wild fish by the wild fish sector that has prompted the imposition of SEPA’s Sea Lice Risk Framework on the salmon farming industry, even though I believe that the claims are largely unfounded.

I will submit another request to SEPA to ask what conclusions they reached after analysing this data, but I suspect that like the Marine Directorate before them, no analysis of the data is carried out. In my opinion they could see that one fish carried 134 lice and that was sufficient proof that sea lice control was required even though one fish with a lice load of 134 lice is entirely normal in the wider population. The next highest lice count on one fish was 93. Again, one fish carrying 93 lice is something that would be expected in nature.

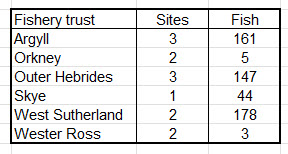

In total, the six fisheries trusts sampled a total of 538 fish during 2025. The breakdown of the number of sites and the number of fish caught is shown in the following table.

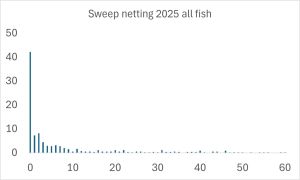

There is no record of whether fyke nets were used this year so it must be assumed all the fish were caught by seine net. If the total number of fish sampled in 2025 is shown as the percentage fish infested against increasing lice counts, then the resulting graph is shown as follows.:

The percentage of the fish sampled carrying no lice is 42.2% with 80.1% falling below the 13 lice threshold set by Wells et al. (2006) (Dr Alan Wells, now of Fisheries Management Scotland).

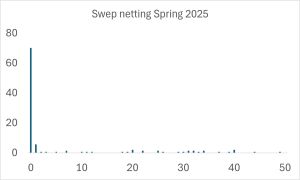

However, of the 538 fish sampled, just 246 were sampled during the period when salmon smolts in the wild migrate out to their feeding grounds. This is the period when the established narrative about sea lice suggests that salmon smolts are at risk of being infested with sea lice that could lead to their deaths. The remaining 292 fish were sampled in the summer and autumn long after the salmon smolts have left Scottish waters.

According to the Atlantic Salmon Trust, the smolt migration lasts until the end of spring. They do not clarify whether this is the meteorological or the astronomical spring, the last date of which is 20th June. During the spring migration, the six fisheries trusts sampled eight sites in total and the number of fish caught at each site is shown in the following table:

Interestingly, there is a protocol for sampling sea trout for sea lice. This was drawn up by the Scottish Fisheries Coordination Centre (now part of FMS) and the Marine Directorate. SEPA have confirmed through an FOI that this is the protocol that they follow.

The protocol states that sampling should be carried out on three days in May and June and aim to catch a minimum of 30 fish. The protocol also states that limitations of time and personnel may mean that the trusts are limited to sampling a single site in any given area, but priority should be given to sampling a single site a number of times rather than sampling once at three different sites. Clearly, the above table would suggest that the trusts have not followed the protocol either by focussing on one site multiple times or by attaining a minimum of 30 fish.

Whilst there has been little attempt to analyse the data over the years, at least one fisheries trust uses the Taranger formula to assess the potential mortality of the fish. Despite its widespread use in Norway, this approach is not assured, and I know that because Geir Lasse Taranger told me this himself. Some years ago, I had a zoom call with him in which he said that the calculated mortality could only be considered an estimate as much more work was needed to refine and validate the formula. However, as we know, this work has never been carried out.

Regardless of the inherent weakness of this approach, using both the variants for fish under and above 150g, the estimated mortality of the fish sampled in 2025 was 16%, which means that 84% of the fish would survive. We also know from work of the Wester Ross Fisheries Trust that sea trout can lose their lice load, so the estimated mortality is just that, estimated.

When analysing the data collected during the spring migration and including only the fish that meet the sweep netting protocol, then 70% of the fish sampled would be lice free and 80% would be under the Wells number with 18% mortality according to Taranger. The distribution of sea lice on these fish is shown in the following graph.

Although sweep netting for sea lice infested sea trout along the west coast has been organised since 1997, there has never been any real attempt to assess whether the fish in the wild actually die or not. A simple tagging and recapture trial might have shed some light on real life mortality, but the scientific community has never been interested in validating the established narrative that fish populations are compromised by sea lice.

In addition, the scientific community has also been slow to analyse the relationship between lice on salmon farms and lice on wild fish using actual data. Although sweep netting for wild fish has been undertaken for the last 28 years, most of the data has never been analysed. It was only in 2024 that the scientists at Marine Scotland published a paper in which they tried to link the lice on farms with wild fish infestation. Despite the wealth of data, they chose to only look at a five-year span between 2013 and 2017 because of alleged changes to the way lice were recorded in 2013 and again in 2018. The scientists chose to analyse the data using models from which they concluded that lice on farm caused increased lice on wild fish.

As lice data on farms is now freely available (unlike the lice data on wild fish), it is possible to look at the relationship between some of the sampling sites and their nearby farms.

Of the thirteen sites sampled by the trusts, three had lice numbers that did not appear to fit the aggregated distribution of lice amongst host fish. By this, I mean that the fish sampled all carried lice with just one or two free of any lice, although lice free fish still dominate the sample.

Two of the three sites had just one farm in the near vicinity with other farms a significant distance away. The third site has two farms sited locally.

The farm in Loch Sealg in the Outer Hebrides is Caolas A Deas. According to the data available on the Scotland Aquaculture website, sea lice levels were recorded from week 9. By week 22 when the sweep netting first took place, the highest lice count was 0.4 adult females. The average lice count on-farm until then was 0.11. In week 22, the total lice count for the 30 fish sampled was 782 copepods and chalimus, 24 mobile preadults and 20 gravid females with an average of 26, 0.8 and 0.03 respectively. The lice levels on-farm was even below the limits set by Norway so it is difficult to implicate the farm in the high lice counts on the wild fish.

The Loch Sealg site was sampled again in July. The highest farm count between the two dates was 0.21 adult females and the average count since stocking was 0.12. In July, the total lice load on 30 sampled fish was 841 copepods and chalimus, 377 mobile preadults and 13 gravid females, which gives an average of 28, 13 and 0.43 respectively. Again, the farm levels are low enough not to be the source of the high lice counts on the fish with an average count of 0.12.

The second site was at Borve which has only one farm located nearby. This is Soay. Borve was first sampled in week 22 and produced an average count of 292 copepods and chalimus, 11 mobile preadults and 3 adult females on a sample of 26 fish equating to an average count of 11,2, 0.42 and 0.11 respectively. The farm had been stoked from week one and attained a maximum adult female count of 0.39 with an average of 0.26.

Borve was sampled again in week 30 by which point the farm was beginning to harvest the fish, the average lice count on farm was 0.27 adult females. By comparison, the sample of 30 wild fish were carrying just 41 copepods, 43 mobile preadults and 3 adult females. This equates to an average of 1.4, 1.43 and 0.1 respectively. Therefore, whilst the farm count had increased slightly, the lice loading on the wild fish had diminished.

The third site was in West Loch Tarbert, which was sampled three times. Once was in June, the second in July and the third in August. None of these samplings coincided with the spring smolt migration.

In June, the average lice count was 0.4 copepods, 3.6 mobile preadults and 3 adult females. In July, this changed to 0.25, 5.3 and 1.75 respectively and in August to 4.0, 7.1 and 1.9 respectively. The sample sizes were 5, 12 and 19 fish which may account for some of the changes observed.

The two nearby farms East Tarbert Bay and Druimyeon Bay were either not stocked or lightly stocked with a lice load of 0.002 and zero at the first sampling. At the second sampling, the average lice count was 0.01 and zero and at the third sampling the average count was 0.2 and 0.57. Again, the lice counts on-farm are still relatively low to account for sea lice numbers found on wild fish.

I have also looked at the sites that provided low lice counts on wild fish and compared them with counts on nearby farms. In every case, the farm counts were also very low so no inference could be made.

Finally, I would like to comment on the results from the Wester Ross Fisheries Trust which total just three fish, two of which were caught at Firemore and the third at Boor Bay, both on Loch Ewe. This very low number of fish is surprising because the Wester Ross Fisheries Trust website list fifteen separate netting events at various sites including Torridon, Applecross, Kanaird, Gruinard Bay, and Flowerdale.

The Flowerdale site is the one which is consistently sampled due to the proximity to the trust’s office even though there are no farms locally. Yet despite the absence of a local farm, the Flowerdale site always produces fish with high lice counts. The trust attributes this to high lice levels at the salmon farms further south in Loch Torridon.

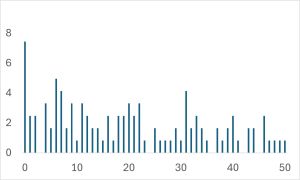

In 2025, the site at Flowerdale was sampled three times in April, July and August. The number of fish caught on these occasions were 30, 5 and 32. The average counts on these fish are shown in the following table:

What is interesting is that the three farms had an average lice count during 2025 of 0.73, 0.39 and 0.44. However, the highest lice counts on all three farms came at the end of the year from August onwards. Before then the average counts were 0.49, 0.39 and 0.35 respectively. These counts do not explain the high lice counts on the wild fish at Flowerdale sampled in April. The sample taken in July was too small to really make any judgement.

Sadly, the Wester Ross Fisheries Trust has failed to adequately monitor the one site of most interest and that is in Loch Ewe. This year they netted the site at Boor Bay in June and caught just one fish which carried 3 copepods and chalimus and 3 preadults. This is the fish that also appears in the SEPA list. Why they decided to net this site is unclear because they didn’t bother to do so in 2024. According to the 2023 review six fish were caught at Boor Bay using a fyke net in 2022 and a further 3 fish were caught by sweep netting at Inverasdale on Loch Ewe in 2021 where one fish was reported as carrying 43 lice.

This highlights the problem of small samples that are rife throughout the twenty-eight years of sweep net sampling that has taken place in Scotland. A report of one fish with 6 or 43 lice is rater meaningless although any fish with a number of lice is seen by the wild fish sector as absolute proof of the damaging impact of salmon farming – a narrative they are determined to maintain whilst wild fish continue to disappear from rivers right before their eyes.

It is clear that there is much more to wild fish infestation with sea lice than simply attributing high counts on wild fish to high counts on local salmon farms.