Spayed: The Times newspaper recently published an interesting article asking why it is that nearly every summer, the usually very wet Scotland, now experiences major water shortages. The issues covered in this article raise other questions that have a much wider significance to both wild salmon and salmon farming.

The article focuses on the River Spey, the third longest river in Scotland at 172 km. The river rises in Loch Spey about 37 km northeast of Fort William. About fifteen kilometres downstream, the river is dammed by the Spey Dam which allows water to be abstracted from the river and diverted to Loch Laggan and then used to provide hydroelectric power to the aluminium smelter in Fort William before entering Loch Linnhe. According to the ‘Release the Spey’ campaign 66% of the river flow is taken from the river at this point. A further 25% is diverted from the river to be used to generate power at the Tummel Valley hydroelectric scheme following which the water is released into the River Tay. These two schemes account for 91% of all the water abstracted from the river Spey.

After the dams, the river winds its way down towards the coast passing through many world-famous whisky distilleries, finally entering the Moray Firth 8km west of Buckie. As well as whisky, the Spey is famous as one of the big four salmon rivers in Scotland.

The Times reports that like many other rivers in the UK; the Spey was subjected to record low water levels from the spring right through to the autumn. Suddenly, there is not enough water to keep the hydroelectric turbines spinning and the whisky distilleries cool whilst preserving wildlife including salmon. This has resulted in a conflict over access to water and according to the Times, it is fish and whisky that are losing the undeclared war and hydroelectric that is winning.

At the heart of this conflict is SEPA (Scottish Environmental Protection Agency) who have declared a significant water scarcity this summer and banned distilleries and farmers from taking water from the river. Some well-known distilleries had to halt production for the whole of the summer until restrictions were lifted in October.

What has angered many associated with the river is that whilst SEPA imposed a ban on abstractions on the lower river, they did not apply upstream, and hence water was still diverted away from the Spey into other catchments, whilst the lower river was allowed to run dry. Anglers and distillery workers do not understand why SEPA have favoured hydroelectric to the needs of the whisky industry and fisheries management.

However, what this shows is that SEPA are totally out of touch, especially with salmon management. In major salmon rivers like the Spey, safeguarding the future of this iconic species clearly takes second place to the demands of others, yet on the west coast SEPA have imposed a Draconian system of regulation to ensure that even just one wild salmon is protected. There is absolutely no consistency and even less thought.

Back on the Spey, the local fisheries’ biologist has estimated that the flow rate is half of what it used to be either twenty or forty years ago. Changes to the climate has not resulted in changes to river management. For example, melting snow has historically meant that there has been a regular supply of cold clear water in the spring. Such snow melts are now a feature of the past and spring waters are hotter with less flow, but yet abstraction continues to be allowed as if nothing has changed.

SEPA admit that this year has been unusually dry with spring water levels the lowest in 70 years. SEPA told the Times that as an effective regulator our role is to balance the needs of businesses with the health of the environment they rely on. Yet, it seems that as far as the Spey is concerned, they have done a poor job. This compares to the west coast where the needs of the salmon farming businesses are not even considered. Instead, it is the needs of the angler that are placed first as SEPA appear to want to first and foremost ensure that the wild fish sector can continue to enjoy their sport, irrespective of the cost to others and more importantly, irrespective of what the science and evidence says.

Science and evidence are very much a part of my life, and I was interested to read in his editorial in Trout and Salmon magazine that Earl Percy, President of the Atlantic Salmon Trust wrote that the work of the trust is guided by science whilst the AST website says evidence is at the heart of what they do. Yet, at the heart of their fund-raising auction are lots that offer fishing on various rivers, including on rivers within the aquaculture zone where SEPA’s regulations are limiting salmon farming because they say wild salmon need protection, but clearly not from angling.

One of the lots offered by the AST is from the Macallan Estate, producers of the famous Macallan whisky, which is for 4 rods fishing one day with the help of Macallan’s ghillie, together with food and accommodation. This is despite the Spey Fishery Board stating on their website that wild salmon are now accepted to be in crisis. They celebrate the fact that 98% of wild salmon are now released but this means that in 2021, using the figures they quote, 120 fish were prevented from breeding because the anglers that caught them wanted to take them for the table.

According to the Spey Fishery Board website, they introduced a salmon conservation policy in 2003 which was initially aimed at achieving a release rate of 50% in order to protect depleted stocks of salmon and grilse. However, they say that the level now is much higher than this original target. Despite the much higher release rate now, the reality is that following on from the introduction of this salmon conservation policy, anglers have caught and killed a total of 31,701 wild salmon, all of which were prevented from spawning and creating the next generation of wild salmon.

The figure of 31,701 fish comes from the official catch data published by the Scottish Government although the number of fish lost to the river is likely to be even higher. Regular readers of reLAKSation may remember that I compared the catch data from all the major Scottish salmon rivers as published in the Fisheries Management Scotland Annual Review with that published in the official Scottish Government catch statistics. I found major discrepancies between the two sets of data, with FMS numbers consistently higher than those published in the official record.

As can be seen from the Spey Fishery Board website, in 2021 a total catch of 5,318 salmon was recorded of which 5,198 were subsequently released and thus 120 were retained.

The 5,318 catch was also reported in the FMS Annual Review, the last year for which river catches were published. That year, I highlighted to the Scottish Government that there were major discrepancies between the numbers recorded by individual fishery boards and the official data. I had expected that the Scottish Government might investigate why the numbers differed, but all that happened was that FMS stopped publishing their data in their Annual Review, otherwise it was business as usual.

Revisiting these numbers now, the official record for the Spey shows a total catch of 4,859 salmon of which 4,754 were released and 105 were retained. This is a difference of 459 fish for the total catch and a difference of 15 fish in the number killed. This represents a difference of around 10%, hardly what can be described as an inconsequential difference.

Back in July, Fisheries Management Scotland published a new guidance video on catch and release. https://fms.scot/new-short-film-urging-anglers-to-help-save-scotlands-wild-salmon-featuring-iconic-scottish-television-actor-and-angler-paul-young/

The message is that best practice reduces the risk that wild salmon will not die after being caught or will improve their chances of spawning, In the video, Professor Neil Metcalfe of the University of Glasgow says that the single biggest impact is to expose the fish to air even for a short period of time as this is something that can really stress the fish. Professor Metcalfe then explains what damage exposure to air can do. I was reminded of his comments as I read the Times article of the Spey abstractions.

This is because the article opened and closed with an interview with Malcolm Newbould, who first cast a line into the Spey sixty years ago. Malcolm is now a part-time ghillie and manages one of the river’s fishing beats. I know Malcolm also contributes fishing reports to Trout and Salmon magazine. Originally from Inverness, his father taught him how to fish, and he got his first permit to fish the Spey when he was ten and it cost half a crown in old money. Mr Newbould is obviously deeply knowledgeable and experienced, so it was surprising to see him pictured with a salmon in the Times along with his two cocker spaniels Harris and Cuilean. Clearly if a ghillie does not follow best practice how can the wider angling community be expected to do so.

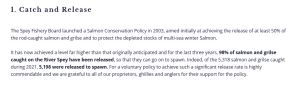

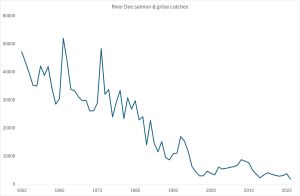

The graph of salmon catches from the Spey as illustrated in the FMS Annual Review does not indicate any particular catch trend but when a trend line is applied to the official data for the river, there is a clear downward trend that was evident before catches across Scotland began to collapse after 2010. The writing on the wall about the Spey catch has been plain to see for many years but largely ignored.

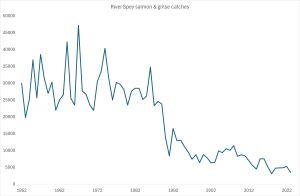

Of course, the rod catch is only part of the story as commercial netting has also had an impact. which is why the angling organisations have been keen to close down these netting activities. When total exploitation for the Spey is examined, it can be seen that the river has been in an increasing perilous state since the early 1980s.

Graphs, similar to this one, can be drawn for the rest of Scotland’s Big Four rivers – Tay, Dee, and Tweed, yet scientists at the Scottish Government always treated rod and netting data separately and thus there is no overall picture and therefore a wider lack of understanding of what is happening to wild salmon stocks.

I recently wrote to the Marine Directorate to highlight these graphs and the long-term decline of other rivers that are still classified as having the highest conservation status. I received a lengthy, but unsigned reply. It seems that there is a great reluctance for any member of the directorate to commit themselves to any statement about wild salmon conservation.

However, the 560-word response I received was simply an explanation of the salmon conservation regulation, which they suggest is something I should, and do, know. Their letter assures me that these key rivers have been assessed as having a good conservation status for the 2026 season.

As far as the Marine Directorate is concerned, all is well. Clearly, anglers fishing the River Spey should have no concerns for the future.

In Deed: Fish Farming Expert reported about a recent debate in the Scottish Parliament concerning the protection of Scotland’s rivers. Of particular interest, was the contribution from Conservative MSP Alexander Burnett, who is a distant relative (fourth cousin once removed) of King Charles III and whose family have owned the Leys Estate on Deeside since 1323. The estate is a well-known destination for salmon anglers.

Mr Burnett’s speech to the Scottish Parliament attracted the attention of Fish Farming Expert because he suggested that the Scottish Government should follow the example of the King’s removal of the Royal Warrant from Mowi salmon and act against salmon farming companies which anglers believe are causing harm to wild salmon stocks, even though Mr Burnett’s estate is located on the east coast where there are no salmon farms, nor have there ever been.

Mr Burnett told the Parliament that the River Dee remains in crisis with wild salmon numbers dropping to critical levels. He added that in 2022, the Scottish Government published its wild salmon strategy but since then no meaningful action has been seen. This is not surprising since the wild salmon strategy is so flawed that it will never produce any meaningful action especially relating to the reversal of the current salmon declines. This is because the strategy is aimed at protecting wild salmon fisheries rather than protecting the fish itself.

Mr Burnett says that one of the most urgent threats that Scotland’s rivers face is seal predation. He added that seals are now often seen far upstream even as far as Banchory near his estate, where they cause significant damage to already vulnerable salmon stocks. He said to understand the issue it is necessary to understand the numbers. Seals eat between four and five thousand salmon on the Dee each year and each salmon will lay more than 6,000 eggs therefore the river is losing about 24 million eggs each year.

Mr Burnett continued that the River Dee’s catch of salmon was 1.500 salmon this year of a population of only 11,000 fish. He said that despite 45% of the Dee’s salmon stock being removed by seals, the Scottish Government has stated that seal control is unnecessary. He argues that this statement directly contradicts the commitments made in April 2024 when NatureScot, the Marine Directorate and Fisheries Management Scotland acknowledged the problem and pledged to find a solution by October. That deadline has long passed, yet seal predation continues unchecked.

It is worth examining the detail behind Mr Burnett’s claims, beginning with the River Dee rod catch for 2025. He says that this was 1,500 fish, although it will not be until May 2026 before the full data is published (although as demonstrated in the previous commentary, even the official data is no guarantee of the actual number of fish caught). At the beginning of October, the River Dee Fishery Board published their last weekly fishing report for 2025 and stated that the final estimate is 1,490 fish although some beats only report catches once a year so the final number will not be known for some time. Given the critical state of salmon stocks, it seems ridiculous in the days of instant news that proprietors are only prepared to report catches once a year.

According to Scottish Government scientists the rod catch represents about 10% of the total salmon stock so with a catch of 1,500 fish, the population would be about 15,000 fish not 11,000 as Mr Burnett suggests. However, if the loss of fish to seals is about 4-5,000 fish, this would bring the number of fish in the stock down towards 11,000 fish.

A letter in the Press & Journal from a well-known local commentator on salmon and especially on salmon farming indicates that the figure of four to five thousand fish being consumed by seals came from a soon to retire ghillie who spoke at the Fishery Board’s recent annual meeting. It is unclear how accurate this figure is as most estimates of loss seems to be based on the number of seals in the vicinity multiplied by their known daily consumption of fish. Of course, these seals eat other fish and not just salmon.

Mr Burnett suggests that the loss of these fish represents a loss of 24 million eggs to the river, but this figure appears to assume that all the fish consumed by seals are female and there are no males.

Mr Burnett asks why the Scottish Government have not taken action against these seals. The answer is simple. Scottish Government scientists use an agreed formula to work out the conservation classification of every river in Scotland based on the number of eggs in the river estimated from the size of the salmon population calculated from the number of fish caught by anglers.

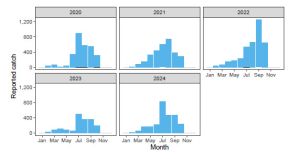

According to the official statistics 2,589 fish were caught from the Dee in 2024 of which 15 were caught and killed despite the imposition of mandatory catch and release. It is impossible to check this number against that used in the conservation status calculation as the catch is shown as a graph. However, if the figure is correct, then this year’s catch of 1,500 fish (1,774 in 2023 – the previous worst year) is well down on that of 2024, appearing to confirm that 2025 could be the worst year on record.

The percentage chance of the River Dee meeting its egg requirement for 2024 was 82.68% with a five-year average of 83.05% meaning that the river falls above the 80% cut off confirming its status as having a good conservation status. In my opinion, it seems that this good rating means that Scottish Government scientists consider the river has sufficient eggs and therefore does not need any extra help especially if the extra help would be the contentious issue of shooting seals.

Interestingly, the river’s percentage of meeting its egg requirement fell in 2023 to 67.14%, yet because of the way the way the scientists calculate the figure using a five-year average, the reduced conservation classification is erased, and the river retains its Grade 1 – good conservation status.

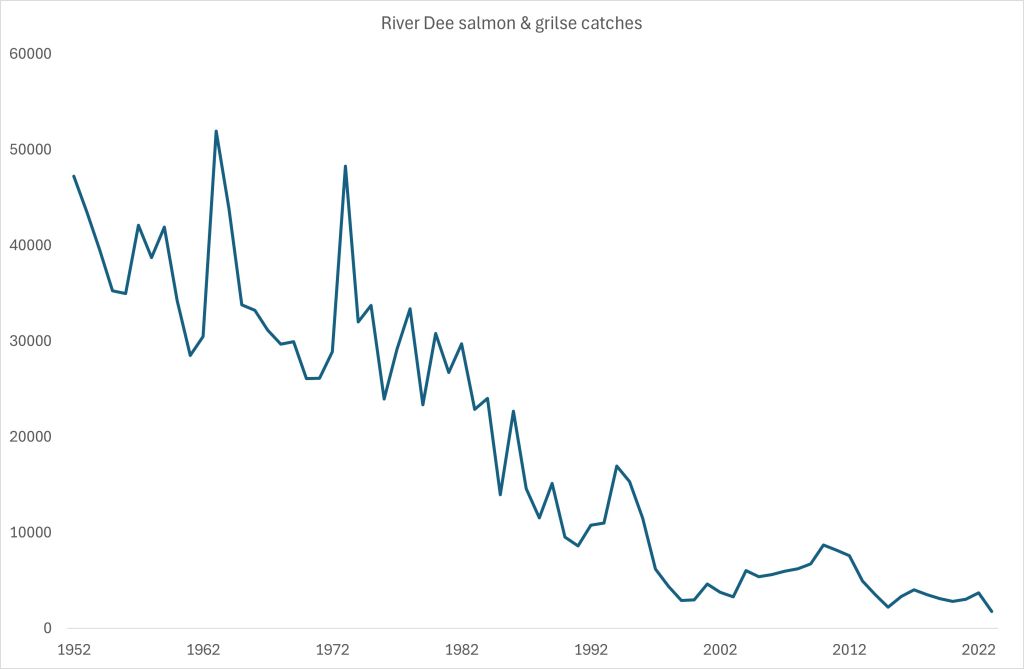

Whilst Scottish Government scientists promote the River Dee as having a good conservation status, the catch data from over seventy years tells a different story.

The graph from the last FMS Annual Review to include catch data in 2022 also tells the same story and so those involved in the river cannot be unaware of the poor state of the river. This why over twenty years ago, the river was made mandatory catch and release but clearly, that measure has had no impact on the catches and hence the salmon stock.

The picture is even more alarming if total exploitation is considered.

Yet as already highlighted in this issue of reLAKSation, the scientists at the Marine Directorate don’t consider the graph has any merit. Instead, the fact the river has been classified as a Grade 1 river is sufficient to allay any concerns.

My own view is that if Alexander Burnett is concerned then he should call for a wider discussion on wild salmon declines rather than rely on Marine Directorate advice. At the same time, he should be urging the Scottish Government to act rather than asking them to divert their attention away from concerns about wild fish and listen to the views of a handful of campaigners and activists who work against the salmon farming industry.