Uncertainty: Following on from the commentary in the last issue of reLAKSation about sentinel cages, it is worth noting that the Sea Lice Expert Group report includes a section on the uncertainties associated with the use of sentinel cages.

They begin by suggesting that infestation will vary with the transport of water through the cages. Clearly, there will be greater flow if the cage is sited where there’s a strong current compared to where water flow is minimal. However, I would expect that the sentinel cages are located where the sea lice dispersal shows there to be a flow of sea lice not in some randomly chosen location. Some of the sentinel cages are also located close to nearby salmon farms and this increases the chance of infestation and misleading conclusions because we know that lice can be found close to farms but not as distance increases away from a farm.

At the same time, the Expert Group say that the fish remain in a fixed location so rely on the currents bringing the lice to them whereas in nature the fish move and thus the contact between fish and lice will probably be much higher. I have noticed that the scientific community regularly take the view that in nature whatever interaction they see is usually worse in nature. I disagree and have used the example of a person standing still in a roadway and who is more likely to be hit by a car than someone running back and forth across the road.

The Expert Group also point out that the sentinel cages are deployed relatively close to land as they have not yet worked out how to deploy them in the main body of the fjord. This mean that their estimated infection pressure relates only to near shore not the water body as a whole. Thus, their estimation cannot be considered representative of what is happening in the Hardangerfjord system.

The Expert Group highlight studies looking at the variation between cages by placing 13 pairs of cages placed 50-100m apart along the Hardangerfjord. Seven of the pairs showed very low infestation pressure whilst the other six sets showed higher infestation of which four sets showed very different levels of infestation pressure between the two paired cages. I would have liked to look at this data but the reference to this work is different in different reports, and I have yet to trace the primary work. The Expert Group say that the reason for the difference in between the two cages in these four pairs could be due to local currents, uneven distribution of lice in the water, fouling of the cages so reducing flow or different behaviour of fish in the cages or other coincidences. I would argue that the Exert Group are clutching at straws in proposing such possible differences, whilst at the same time ignoring what is probably the most important factor in the process of infestation.

The Expert Group appear to treat sea lice infestation in isolation of nature. They just seem to consider salmon farms as the only source of sea lice, but sea lice have probably been infesting wild fish since eternity. They are present wherever there are wild fish including in the fjords occupied by salmon farms. Unfortunately, because all the research effort is aimed at trying to prove salmon farms are the cause of wild salmon declines, we actually know very little about how wild salmon become infested in areas where there are no salmon farms. Equally, we don’t know how salmon farms in totally new areas become infested in the first place. For example, the most contentious salmon farm in Scotland in Loch Ewe was located 55 miles from the nearest farm in one direction and 40 miles in the other and neither were in direct line of sight. When the farm was first stocked in 1988, the fish were all lice free yet within a few months anglers were claiming that lice from the farm had destroyed the world-renowned sea trout fishery in Loch Maree.

It’s most likely that lice transfer from fish to fish and any wild fish swimming around a salmon farm ensure the farm becomes seeded with their first lice. There is clear photographic evidence that wild fish can lose many of their lice and undoubtedly, they transfer to both other wild fish and to fish held in captivity whether on a farm or in a sentinel cage. Salmon are a shoaling fish, and shoaling provides another opportunity to transfer. It wouldn’t take much effort to attach cameras to sentinel cages to see what other interaction occurs in the vicinity.

The Expert Group then quote from a recent study, which just happens to be authored by the leader of the Expert Group. This is yet another example of how the view on sea lice infestation is governed by vested interests and blinkered vision. The study claims that a given infection pressure, the lice burden of salmon in a sentinel cage is 90% lower than that of wild caught post smolts caught during the annual trawls.

It is unclear why the Exprt Group consider this an uncertainty when common sense would say that wild migrating smolts are more likely to be infested than those in sentinel cages. This is because the wild salmon are naturally infested just as they would be if there were no salmon farms. Sea lice are parasites and parasites must find a host to survive. They tend to be extremely specialised to maximise their host location and in salmon lice, this is most likely to occur at the freshwater- seawater interface. The likely route of infestation is still conjecture (because everyone is focused on salmon farms as a source of infection) but there are examples of infection with other similar parasites that should be explored. Therefore, if the Expert Group have found ‘high’ infestation of post smolts then the likelihood is that it is a natural infestation and not one from encountering infective sea lice larvae. The Expert Group should also consider that these fish are caught on their route from rivers to sea and have not spent much time in the fjord prior to capture.

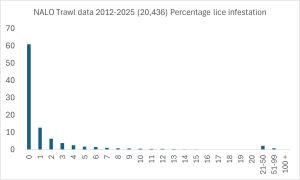

When all the trawl data from Hardangerfjord is plotted, it can be seen that the lice are spread as a classic aggregated distribution and that 60% of the trawled post-smolts are totally free of lice.

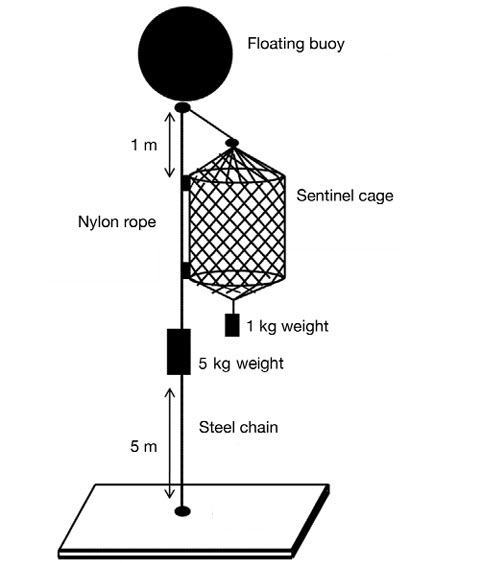

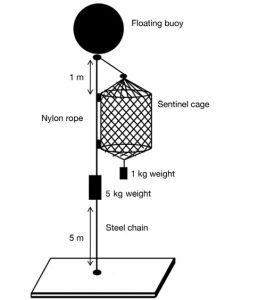

In discussing the uncertainties relating to sentinel cages, the Expert Group have ignored one the most significant uncertainties and the reason why they have likely ignored it is because it is more of a certainty and that relates to the treatment of the fish and related welfare issues. The following diagram is taken from one of the papers about sentinel cages in Norway. It shows the way sentinel cages are set up.

I think that there would be a public outcry if a farming company were to cram 30 fish in such a small cage which prevented the fish from reaching the surface to adjust their swim bladders and then holding them for two weeks without any food, yet it seems that research institutes can do it in the name of science.

The 2025 sentinel cage data focussed mainly on the Hardangerfjord but the dataset included two deployments of two cages at Austevoll totalling 115 fish. After a little digging, it was apparent that these two cages were deployed at the Austevoll Aquaculture Research Station. One cage was labelled as old cage and the other as new cage which led me to believe that IMR were trialling a new sentinel cage, even though they have not expressed any uncertainties over the old one and have deployed them without comment for over a decade.

I have now secured a summary of the application that IMR made to the Norwegian Food Safety Authority to test a new cage design. The application represents part of a larger interval revision of the methodology with the emphasis on improving animal welfare. They say that the design will be such that the data can be compared to that produced in the existing cages. The new cage will be held so the bottom will be at the same depth as the bottom of the existing cages, but the cage will be double in size and thus will reach the surface. The new cage will also have a mounting to include a feeder, but this will not be tested initially.

In addition to the new cage design IMR want to refine the protocol for the whole process including a reduction in the amount of handling of the fish. They are also looking at reducing the number of fish from 30 to20.Their goal is to develop a new minimum international standard for the use of sentinel cages. Something SEPA in Scotland have said that they would contribute towards, not that they seem to know much about sentinel cages.

From the dataset, it is possible to determine the exact location of the sentinel cages.

The image shows the location of the existing sentinel cage (lefthand and approx. 425 m from the farm) and the new cage (to the right and approx. 85 m from the farm).

The first deployment ran from 27th May to 12th June and at the end 26 fish were harvested from the new cage with an average lice count of 8.2 lice each. By comparison, 29 fish were harvested from the old cage with an average lice count of 11.2.

All 30 fish were harvested from both cages at the end of the second deployment which ran from 12th to 26th June. The average lice count was 0.9 on the new cage and 1,2 on the old cage.

It’s difficult to make any deduction from these results. The new cage appears to give lower readings but, in my opinion, it should have been positioned nearer the old cage. Instead, the distances are different as well as the location. Whilst the new cage gives a lower reading, more fish died from that cage.

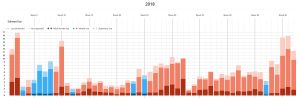

However, what I find most interesting is that this research station farm appears unable to control the lice numbers as can be seen from the following graph.

In fact, the farm has struggled over the years to control lice. For example, the data for 2018 is shown below and is clearly well above the regulated limit for almost all of the year.

With all their scientific expertise, the inability to control lice is a real puzzle. What is even more puzzling is that the Austevoll Research Station is the location of a 1997 study by Karin Boxaspen, now of Sea Lice Steering Group from which she reported her inability to find any lice larvae in the vicinity of the station. Given the high levels of lice recorded at the station, it is surprising that her quest has never been repeated. Given the trials of the new sentinel cages, this year would have been an ideal opportunity to try to show that lice are actually present in the vicinity of the research station,

The problem is that whilst IMR continue to deploy sentinel cages, the data is not matched to the actual presence of sea lice on farms at the time. Instead, the data is applied to their model and that tells us nothing. As I revealed in the last issue of reLAKSation, the elevated lice levels at two of the 83 farms in the Hardangerfjord does not relate at all to the data from sentinel cages.

The whole process needs a complete rethink not a redesign of the actual cage.

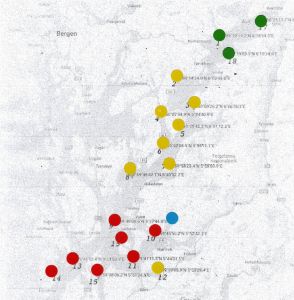

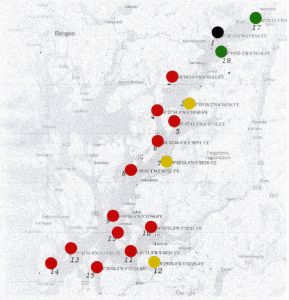

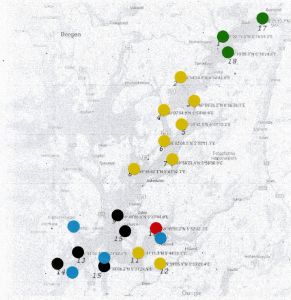

2020: Most of the data form sentinel cages from the Hardangerfjord shows low infestation but 2020 was an exception. My analysis of the data differs slightly from IMR’s findings, so I have replotted the three deployments for that year. I have also added the location of any farm that has exceeded the lice limit during the deployments as far as the data allows. This is one farm in the first deployment, no farms in the second and four in deployment 3. These are shown in blue. In addition, sentinels shown in black are where no data was recovered.

How these provide any indication of lice infestation pressure is a puzzle which is why the scientific community prefer to use their models instead to estimate the pressure. The key question arising from the sentinel cage data is whether we are sure that the farms are to blame or is the collected data the consequence of natural lice infestations.

Deployment 1

Deployment 1

Deployment 2

Deployment 2

Deployment 3

Deployment 3

Trust: The Institute of Marine Research is 125 years old. To celebrate the Institute’s director Nils Gunnar Kvamstø has been interviewed and highlighted three challenges which will shape marine research in the years ahead. These are climate change, pressure on coastal zone and the third is trust.

He says that this is a problem that has affected public discourse because we don’t know what information we can actually trust. He says this is why IMR must continue to be open and honest about the information we communicate, whether good or bad.

He adds that it is important to explain how we have arrived at the knowledge we impart so that people out there know it can be trusted.

Unfortunately, when it comes to sea lice, it seems that IMR have forgotten how to be open and honest and that the public must accept whatever IMR say. For me, the fact that IMR appear extremely reluctant to enter into any discussion about sea lice means that any trust simply does not exist.