Talk, Talk : The latest edition of the ‘Last Salmon’ podcast hosted by anti-salmon farm angler and actor Jim Murray MBE visits the Gaula River in Norway and talks to Ann-Britt Bogen of Gaula Flyfishers and Matt Hayes, You-Tuber and owner of a fishing lodge on the river. (https://thelastsalmonpodcast.com/)

There were a couple of parts of the discussion about the Gaula that I found of interest, which I may return to, but the main point was when Jim Murray asked the three questions that he asks of all his guests. One of these is what would he do to save wild salmon if he had a billion pounds to spend.

Matt Hayes replied that it’s not all about the money but rather about making the right decisions and biggest decision he would take would be to talk to the salmon farming industry, adding that ‘we don’t talk to them enough.’ He continued that he might use some of this theoretical funding to influence key public figures to help get a platform for us to sit down with the salmon farmers in a serious manner and to negotiate.

Now I am not sure why Mr Hayes thinks he needs to influence public figures to instigate discussions with the salmon farming industry. I think he should just ask. However, Mr Hayes comments suggest that any negotiation may involve just a list of demands which in return would be met with the promise of fewer attacks on the industry. What he actually said was that he would use a carrot and a stick approach. He recognises that the industry might want something in return for meeting his demands.

What Mr Hayes would like is for salmon farms to be removed from around five iconic rivers with a commitment to leave the rivers salmon farm free for five to ten years. I imagine that he might expect that these iconic rivers might recover in this time frame.

In return, he would give salmon farming a big tick as an industry that cares about wild salmon and is prepared to act to save this fish, a message which the wild fish sector would spread on social media. Mr Hayes said that the industry has an incentive to act because they are losing the PR battle about farmed salmon, otherwise the death of wild salmon will be on the salmon farmers’ conscience. He wants to put the squeeze on the salmon farming industry and make them recognise that if they put their mind to it then it is they who can change the fate of wild salmon in Norway.

Whilst I welcome any effort to engage in discussion, I would like the discussion to be open and frank and two-way. Whilst the wild fish sector should be able to express their concerns about salmon farming, the wild fish sector should also be prepared to listen to the industry point of view. All too often, the wild fish sector is happy to shout out their demands but unwilling to sit and listen to the things they don’t want to hear such as maybe salmon farming is not responsible for wild salmon’s problems. For example, Mr Murray’s response to this discussion was to say that whenever the wild fish sector point out to the industry that the death of wild salmon is happening on their watch, they pay to surround themselves by very clever minds whose aim is to convince us that our claims about the industry are wrong.

No doubt Mr Murray will place me in this group because I would like to respond to Mr Hayes hope that he can conduct an experiment to see what happens to wild salmon stocks in key rivers if surrounding salmon farms are closed and removed. I can understand the thinking behind removing salmon farms because in Norway there are so few areas that have no salmon farming operations, so it is unclear what would happen to wild salmon if the farms were removed. I would suggest to Mr Hayes that five to ten years is a long time to wait for an answer., especially as it is possible to answer his question now.

Mr Hayes wants to take five iconic rivers and remove salmon farms and then see what happens. I can go one better and select five iconic salmon rivers that have never been exposed to salmon farms and can show what has happened to their wild salmon stocks over the last 72 years.

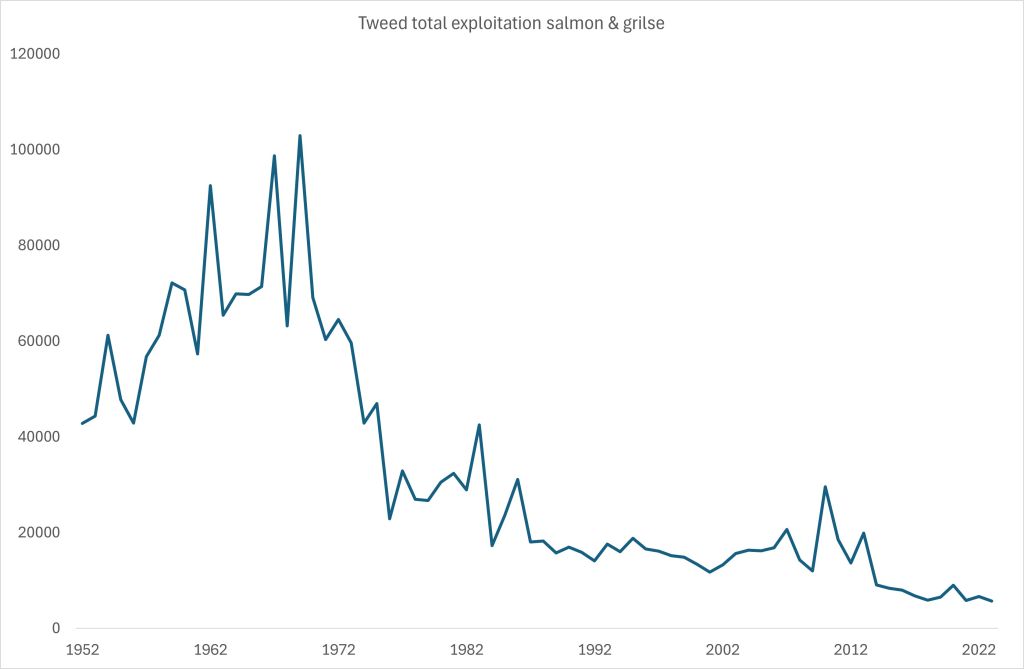

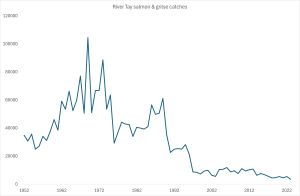

The first of these iconic rivers to consider is the Tweed which empties into the North Sea along the border between Scotland and England. The usual portrayal of salmon catches from the river is shown in the following graph.

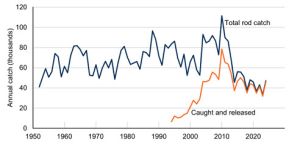

This graph shows that from the 1960s, if not before, rod catches have increased year on year until 2011, when catches collapsed, as they did across all of Scotland. These increasing catches have allowed the river management to be confident through the years in the health of wild fish stocks in the river.

The contribution of the Tweed to the total salmon rod catch can be seen from the official Scottish Government graph of the salmon rod catch, which is very similar to that for Tweed catches.

However, the way that these salmon catches are presented are misleading either for individual rivers or for the total catch. This is because they ignore other activities affecting the wild salmon population, most notably the commercial net catch. When total salmon exploitation for the Rover Tweed is plotted, the graph tells a very different story.

Wild salmon catches from the Tweed have been in decline for the last fifty years and they continue to decline.

It can be seen that catches peaked at the end of the 1960s with 100,000 fish killed in one year alone, three times the current total catch for Scotland. Anyone looking at this graph must surely see that Tweed salmon have been in trouble for many years. Unfortunately, it seems that those in charge of wild fish management, not just of the Tweed, have never considered this illustration of the fate of wild salmon in the River Tweed. Instead, they have focused on the rod catch alone and thus deluded themselves about the state of wild salmon stocks.

However, I have reproduced this graph because Mr Hayes is of the belief that if salmon farms were removed from his river, that given time wild stocks would recover, Yet, it is clear from the Tweed that the problems of wild salmon stocks have nothing to do with salmon farming at all, something that the Norwegian scientific establishment also refuse to consider.

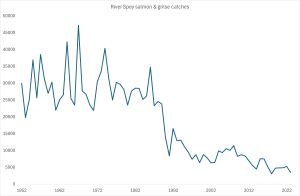

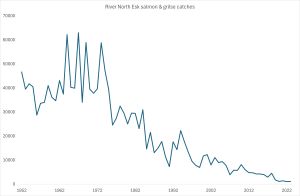

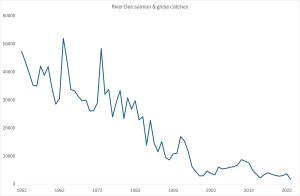

If the exploitation of the other Scottish iconic rivers, the Tay, Spey and Dee are also considered, the pattern of decline tells the same story. I have also included the River North Esk because this is the river that scientists from the Marine Directorate have studied for years through its own dedicated research station in Montrose.

Of these rivers I specifically want to highlight the River Dee because the river management has imposed mandatory catch and release for over twenty years and yet the river is still in trouble. I mention catch and release because it is a subject that Matt Hayes raised in the podcast saying that he saw catch and release as a key management to save the Gaula salmon.

He and Ann-Britt were asked what percentage of the Gaula catch is released.

‘It’s been on average for the last 10-15 years around 60-65% but we have a release rate of 95%.’ He suggests that he likes to attract a certain type of angler who is happy to return fish to the river rather than opting to kill them. Matt Hayes added that there are laws about catch and release in Norway so that they are not allowed to have 100% catch and release.

Interestingly, the data from Statistics Norway for the whole Gaula River for catches since 1993 would suggest that the catch and release rate is just 19.8%, well below the numbers claimed by the guests in this podcast, Clearly, the higher numbers might relate to just a small stretch of the river managed by the two guests of the podcast.

Finally, I would refer back to Mr Hayes wish to talk to the salmon industry. I have written to him about the fate of Scotland’s iconic rivers, and I have not had a reply. This confirms my experience that the wild fish sector is only interested in talking about what they want to talk about. They are not interested in hearing anything that might undermine their claim that salmon farming is the cause of all their problems.

No talk: What is it about critics of the salmon farming industry that they readily speak to the media to criticise the salmon farming industry, but when asked to talk to anyone from the industry, they go deathly silent. It’s a point that should be made to Mark Carney as he comes to decide the future of salmon farming in BC. If those who are ready to criticise salmon farms are not willing to be challenged in the public arena, then perhaps their claims are not worth the media attention they receive.

Undercurrent News recently reported about a dispute that has arisen over a new peer-reviewed study on sea lice in BC’s Broughton Archipelago. Bob Chamberain, chair of the First Nations Wild Salmon Alliance has alleged that the author of the study, Lance Stewardson of Mainstream Biological Consulting has a conflict of interest that he has hidden. He says that the company is contracted by the BC Salmon Farmers Association, and this is not declared in the paper. Mr Stewardson has refuted the allegation saying that there is no contract with BCSFA but they do conduct sampling for some companies for regulatory purposes.

Mr Chamberlain told Undercurrent News that any contractual work undermines credibility as how can anyone working for the industry be impartial.

Sadly, this is a narrative that critics have used for many years. They believe that any data generated for the industry is not credible but any data that supports their claims is.

In a subsequent article in National NewsWatch, Mr Chamberlain maintains that since the removal of salmon farms, stocks of wild salmon have rebounded ushering a return to abundance even though any such claims are clearly premature.

However, what is interesting is that Mr Chamberlain says that peer-reviewed research by scientists from Canada’s ‘leading’ institutions who work with the First Nations and have our trust is clear that salmon farms have a negative impact on wild salmon stocks. These 16 scientists wrote a letter in 2023 to the then fisheries minister highlighting that by supporting salmon farms, the DFO had failed wild salmon.

At the time, whilst happy to write to the minister not one of these 16 expert scientists responded to an invitation to discuss other findings. These scientists at least were affiliated to an institution and were contactable. By comparison, despite being chair of his representative organisation, Mr Chamberlain does not advertise his contact details.

Interestingly, with a little help, I managed to track down a PR company representing Mr Chamberlain. Unfortunately, whilst he is happy to expound his views to the media, he appears to be less forthcoming to even acknowledge attempts to discuss the issues with him.

If Canada is to lose the salmon farming industry for good, surely there must be a proper debate about the issues and if critics like Mr Chamberlain refuse to come out from the woodwork, then the Canadian Government should question the validity of their views.

Effective?: Salmon Business reports that a new study from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) has found broad agreement amongst stakeholders that Norway’s salmon farming regulation are not working as intended.

The strongest concerns are directed at the Traffic Light System which aims to protect wild salmon through controls of sea lice associated with salmon farms. However, the stakeholders consulted as part of this study also highlighted that escapes, nutrient discharges, fish mortality and disease are ignored whilst lice remain the sole criterion.

The problem is that stakeholders consulted failed to understand that the Traffic Light System is not about regulating sea lice but protecting wild salmon. Sadly, the government have also failed to appreciate regulating sea lice on farms has no bearing on the future of wild salmon. This is because they rely on a limited range of views rather than seeking a wide range of views and advice.

The new paper titled ‘Plague of Cholera – Stakeholder perspectives on Norwegian salmon regulations’ by Juliana Haugen is published in the journal ‘Marine Policy’. Unfortunately, Juliana interviewed just 23 stakeholders from industry, environmental groups, fishermen and independent experts. This is a very small sample for a very diverse group of stakeholders.

According to the paper the interviewees included six experts from the academic fields of oceanography, veterinary, economics and political science.

Six experts from the Directorate of Fisheries, The Environment Agency and the Food Safety Authority.

Four representatives from the angling and commercial salmon fishing sector

Three representatives from environmental NGOs

And finally, four representatives from the industry producing and supplying companies.

This means that at best there are three of 23 contributors who speak for the salmon farming industry on who this research is focussed. It is not even clear if they are experts or just people who shout the loudest.

This domination by others from outside the salmon farming industry in the decision process about salmon farming is best illustrated by looking at the make-up of the Sea Lice Expert Group. The salmon industry is totally excluded and instead, the decisions are taken by a small group of scientists who cannot be considered impartial as they are also directly involved in the research.

Whether the findings of this PhD study can be considered valid depended on the identity of the various stakeholders who were questioned. This is something we will never know.