SIWG 2: This week, the Scottish Environment Protection Agency held two information sessions on their new sea lice regulatory framework. A question posed during one of the sessions prompted a heated discussion on the one-line chat that merits consideration here. I will discuss this without specific reference to the people involved.

One of the sections of the sessions was titled ‘Driving improvements in salmon populations’ and included a presentation about the Scottish Government’s wild salmon strategy in relation to west coast salmon populations. A graphic highlighted some of the pressures facing wild salmon including exploitation which was described as illegal fishing and poaching. One of the participants posed the question on chat about the failure to mention legal fishing i.e. rod and line fishing by anglers. At exactly the same time, I posed a similar question as to why the salmon industry were facing draconian measures to protect wild salmon when anglers were able to catch and kill wild fish from 33 rivers within the Aquaculture Zone, Was the salmon industry protecting wild salmon simply so anglers could continue to go fishing. I cited the example that commercial netting had been banned in Scotland after which the salmon rod catch had increased.

The answer was that anglers in Scotland were now returning 97% of the fish they caught and even though catch and release resulted in some mortality, this was minor. The explanation given was that the rod catch was estimated as being about 10% of the total salmon population and that typically mortality from catch and release was about 10%. This meant that overall, mortality from catch and release angling (excluding the 3% that were actually being killed directly by anglers) amounted to about 1% and was therefore not significant.

In a follow up to the original question I highlighted that the work of the Irish Marine Institute team headed by Dave Jackson who published a paper in 2013 found that the mortality of migrating smolts attributed to sea was also 1%. Clearly, if 1% mortality of wild fish due to catch and release is not considered significant then 1% mortality due to sea lice cannot be deemed to be significant either and thus SEPA’s sea lice regulation framework (as well as Norway’s Traffic Light System) serves no valid purpose.

The response to my question was passed to two scientists from the same organisation and a link was posted in the chat to the Scottish Government’s summary of information relating to impacts of salmon lice from fish farms on wild sea trout and salmon (https://www.gov.scot/publications/summary-of-information-relating-to-impacts-of-salmon-lice-from-fish-farms-on-wild-scottish-sea-trout-and-salmon/). This states:

Multiple studies conducted in Ireland and Norway using artificially reared salmon smolts have found that treatment with anti-sea lice agent increases likelihood of fish survival to return as adults (Vollset et al. 2016). The assumption from this is that protection of the emerging smolts from sea lice acquired in the coastal zone enhanced the ‘at sea’ survival. There is a great deal of year-to-year and site-to-site variation in the magnitude of such an effect; the reduction in numbers of returning salmon associated with lice in untreated smolts is in the range of 0-39% (Jackson et al. 2011; Krkošek et al. 2013; Skilbrei et al. 2013; Vollset et al. 2016).

It should be noted at this point that the paper by Jackson from 2013 is not included in this summary of information. It’s also important to point out that two of the papers referenced above do not create new data but conduct a different statistical analysis of the data from the other two papers.

The chat continued with an explanation of why the 1% I quoted is considered by some scientists to be incorrect. – “As an example, if 5% of the emigrating smolts return as adults in the absence of lice and this reduces by 1% to 4% of returning adults when lice are present then the reduction in adult salmon due to lice would be 20%.

One of the papers referenced above actually arrived at a figure 39% mortality due to sea lice and at the time, this created a great deal of controversy. Simply, it makes no sense that if 95% of salmon are failing to return to freshwater across all of Scotland, then another 39% cannot be dying from sea lice. Alternatively, the 39% could be 39% of the 5% that do return which would be just under 2%. This would make it about 1% more than that reported by Jackson.

Unfortunately, the 39% figure received all the press coverage and as a consequence, the Irish state agency – The Marine Institute produced a video to explain the confusion. This is available on Vimeo at https://vimeo.com/83845976. However, in the time since the Marine Institute’s video was posted over ten years ago, Vimeo now require registration and a log-in to view. I therefore will transcribe the video to demonstrate how even highly regarded scientists have misunderstood the impacts of sea lice.

The video is titled ‘Are sea lice the cause of the decline in our wild salmon stocks’ . The following is taken directly from the video.

When migrating wild salmon smolts go to sea they encounter many life forms that are not present in freshwater. Among the natural marine life is the sea lice. This is part of the natural marine ecosystem, and it lives on the skin of the salmon. This is perfectly normal. Salmon and sea lice have co-existed for millions of years. However, whilst mature salmon can accommodate sea lice without any ill effects, smolts can under certain circumstances be overburdened.

Over the past thirty years, the numbers of salmon returning to our rivers has declined. In the 1980s, the numbers returning was around 25%. Today (2013) the number is about 5%. This has worried fisheries scientists who have been searching for the cause of this decline. Some researchers put forward a theory that sea lice infestation of the smolts could be a major factor in the decline of marine survival. It was also claimed that this was due to an increase in sea lice populations in river mouths due to salmon farming. If it were found to be true, this would have severe implications for the survival of the Atlantic salmon as a wild species.

As the state agency responsible for marine science and research in Ireland, the Marine Institute decided to test out the theory. It carried out a very long and very large series of experiments to test the impact of sea lice on young salmon. It involved 350,000 salmon smolts released in to eight rivers over a nine-year period. One half of the fish were treated with a veterinary medicine which protected the salmon from sea lice for the first six weeks at sea whilst the other half were not.

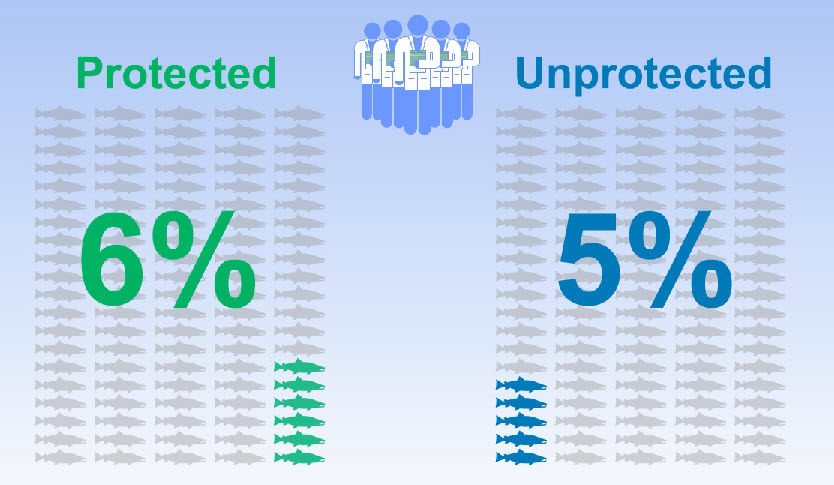

The numbers returning in each batch were counted and then the batches were compared to see if the protected fish did better than the others. The results were very interesting. There was a difference, but it was very small. On average across all the experiments it amounted to just 1%. In other words of every 100 fish leaving our rivers just one does not return because of sea lice. The other 94 that do not return are lost at sea for other reasons.

An almost identical series of experiments carried out in Norway at around the same time came up with very similar findings. Also, both experimental groups, treated and untreated had a similar rate of loss as the wild stocks in the rivers showing that they too were experiencing the same conditions. Interestingly, the results of the experiments were the same, whether the river used to carry out the experiments had a salmon farm or not. Even on the occasion when those farms reported a high incidence of lice, the results were the same indicating that there was no connection between the salmon farms and the survival pattern of the smolts at sea. These two large scale independent studies clearly tell us that the reduction in the numbers of salmon returning to our rivers over the past thirty years is not the result of sea lice and therefore can have little or nothing to do with salmon farming activity.

Based on this work the Marine Institute has been able to conclude that the sea lice are a minor and irregular component of the mortality of wild salmon. They also stated that the effect of sea lice is not large enough to significantly influence the conservation of salmon stocks.

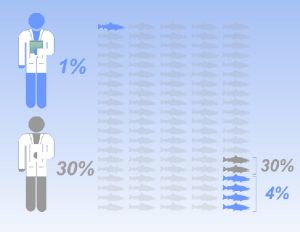

Not everybody agrees with this analysis. Another group of scientists analysed the Marine Institute’s data. Using a different type of statistical analysis, they came to the conclusion that the Marine Institute’s group had marginally underestimated the effect of sea lice. They calculated it was closer to 2%. The important point was whether it was 1% or 2% it still remains a minor and irregular component of overall marine mortality. However, these scientists went a step further and tried to transfer this 2% over to make a comparison with the very small number of fish actually returning to the rivers. They reasoned that if the influence of sea lice was somehow eliminated then instead of 4 fish returning, six would come back. They then suggested that this represented a 30% influence on salmon survival attributed to sea lice. This has caused a lot of confusion. The argument has been presented simplistically in the media, with the Marine Institute saying that sea lice caused 1% mortality whilst the other group say it caused 30% mortality. People don’t know who to believe. In fact, if one compares like with like, both groups hardly differ at all. They both agree that the influence is small but by applying the effect to very low numbers of fish returning one group have grossly exaggerated the position.

Sadly, the Scottish Government’s summary of the impacts of sea lice has perpetuated this false impression whilst their scientists consistently refuse to discuss this and other science. I think I first asked for an opportunity to discuss the science back in 2015 and my requests have been refused every time. The science was never discussed in the Salmon Interactions Working Group meetings because it was considered too contentious and because the wild fish sector could not accept that the impact of sea lice is actually very small. Now we have a new regulator (SEPA) who are equally reluctant to discuss the science. Yet, science is at the very heart of the sea lice framework. Is the Scottish salmon farming industry going to be regulated based on flawed science? When no-one from Scottish Government or the regulator is willing to discuss the science, then there is only one conclusion.

During the SEPA sea lice framework information sessions, reference was made to organising modelling and monitoring discussion groups with stakeholders. Surely, the most critically needed discussion group is one that will discuss the science. Why can’t there be a group formed that will continually review the science? I propose the formation of SIWG 2.

The urgent need for SIWG 2 was immediately apparent from the second information session. This included a section on lice monitoring on wild fish. The speaker said that robust samples were needed so I posed the question how many fish were required to make the sample is robust. The answer from SEPA was 30 fish which is the number from the sea lice netting protocol. There are many reasons why 30 is not a robust sample which I will explain another time. However, another answer appeared in the chat from the scientist who answered my other question. This said that a sample is robust if it is large enough to answer your questions. I responded by saying that as yet, and despite having annual data from 1997 onwards, there has not been a single published analysis of all the sea lice data that answers any questions.

After the meeting, I was sent a link to a prepublication abstract of a new paper titled “Association of ectoparasite sea lice counts on farmed Atlantic salmon and wild sea trout in Scotland”. The abstract doesn’t indicate anything about the amount of data used, i.e. whether it is one year or twenty-three years etc. Surely, this paper should be discussed now and not when its published. I already question its validity because I know that 82% of the Scottish sea lice data does not meet the levels set by the protocol and therefore is invalid. However, I also know that such protocols are ignored if the data implicates the salmon farming industry. As far as some members of the wild fish sector, just one sea trout carrying many sea lice, is sufficient proof that salmon farms are harming wild stocks.

As I have repeatedly written, if scientists or wild fish people firmly believe that salmon farming is responsible for a significant decline in wild fish numbers, as was stated in the chat, then there should be a willingness to stand up and defend the view in front of industry scientists.

Finally, another scientist entered into the SEPA session chat discussion suggesting that the 1% of mortality experienced by catch and release angling was 1% of the 4% of fish that return to the rivers putting mortality due to catch and release at 0.4% and the percentage returning fish at 3.96%.

However, as the presentation about the Wild Salmon Strategy suggests, the impact of angling on salmon’s decline is very much played down by the Scottish Government. Yes, the percentage of fish now returned by anglers is 97% and mortality due to catch and release could be 1%, (although reference to Canadian research would suggest this is on the low side) but it should not be forgotten that not so long ago, this was not always the case. The decline of wild salmon may be due to issues at sea but the loss of 3.65 million salmon and 2.28 million sea trout from Scottish rivers due to angling must have had a major impact on the rate of the decline. This equates to 77% and 82% mortality respectively.