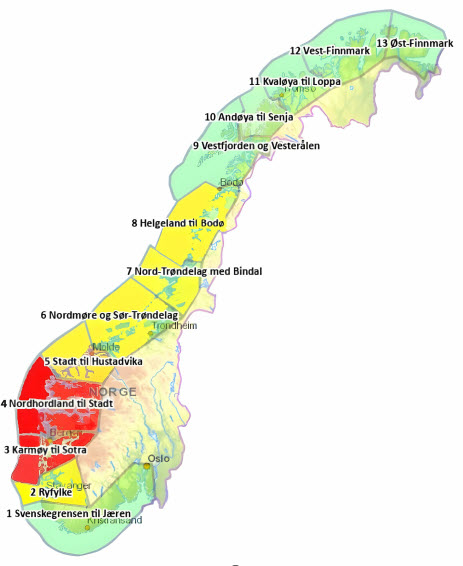

Red rag: The total salmon catch from the Norwegian River Etne in Vestland expressed in kilograms from 1993 to 2023, according to data from Statistics Norway, is shown in the following graph:

The river Etne is considered to be one of the best salmon fishing rivers in Western Norway but because of negative stock development the river was closed to fishing for four years. It is not clear from the graph why this decision was taken. Certainly, the website Elveguiden does not mention the presence of salmon farms as a possible reason. Unfortunately, the data only begins in 1993 so it is difficult to analyse the development of catches over a longer period of time.

The Norwegian Salmon Rivers who represent the interests of salmon anglers highlight (in large lettering) just the catch data from 2023. In total 2,367 fish were caught with an average weight of 3.49 kg. 21 fish were over 7kg and 109 were under 3 kg.

If a trend line is applied to the graph, it shows that the river is in decline. However. the overall trend is significantly influenced by the closure of the river to fishing for four years. However, a cursory examination of catches in recent years would suggest that catches are lower than they used to be. The question is are these lower catches the result of the impact of salmon farming and especially sea lice. The overriding view of the Norwegian scientific community as well as the salmon anglers, is that sea lice are to blame. This is why Norway has introduced the Traffic Light System to regulate salmon production along the Norwegian coast.

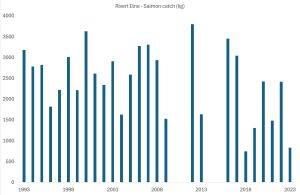

Yet, if we look to a salmon river across the other side of the North Sea (approx. 600 km) such as the river Tay, one of the most famous salmon rivers in Scotland and look at the graph of salmon catches from that river (expressed in numbers) then it is clear that salmon catches have also been in decline there.

However, there are no salmon farms anywhere near to the river Tay. One or two social media commentators have suggested that the Tay is in decline is because salmon smolts from the river swim north past the salmon farms of Orkney and Shetland and pick up sea lice there which leads to their deaths. However, if river Tay salmon smolts do swim that way, then they have also done so from the 1980s to 2010 when all east coast rivers saw catches increase. No-one complained about salmon farms in Orkney and Shetland over those thirty years,

Could it that the salmon catches from the river Etne are in decline for the same reasons that the river Tay is in decline? The simple answer is that we don’t know, and the reason why we don’t know is because the scientific community in both Norway and Scotland are so busy targeting sea lice as the cause of the decline that there is little consideration given to any other reason.

Over recent years, I have examined the relationship between changes in salmon numbers in various rivers and the arrival of salmon farms to the area and it is difficult to find any connection. Instead, there are often other reasons why the river catches have fallen but the scientists in Marine Directorate and the new regulator organisation have shown no interest in these analyses because of the blinkered view towards sea lice.

Since November, when the Institute of Marine Research published their sea lice risk report, I have been analysing the latest Norwegian sea lice data and looking through the various associated reports. These documents are all in Norwegian and it is possible that I have missed something, but I cannot find any reference to sea lice and the actual state of wild salmon populations in Norway. Instead, the focus is very much on the modelling of sea lice infestations.

In Scotland, the Marine Directorate have said that there is a relationship between the number of fish caught by anglers and the size of the salmon population in the river, so the size of the catch provides an estimate of the number of fish actually in the river. However, if there is no analysis of the salmon catch from rivers in relation to the sea lice counts, then how can the impact of sea lice be assessed and hence what is the point of the Traffic Light System? If we don’t know the size of the fish population and how it has changed over time, then surely the regulation is totally theoretical, based on a view (originating from anglers) that sea lice are the reason that numbers of salmon have fallen in the rivers. The anglers have made extremely clear that it must be sea lice as the declines are in no way due to the fact that they have been catching and killing the fish themselves.

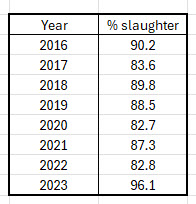

The following table shows the percentage of salmon caught from the river Etne since 2016 that have been killed after being caught,

The average percentage of fish killed is 87.6% peaking at 96.1% in the most recent year. It could be suggested that whilst the salmon farming industry is being encouraged to show restraint, the anglers are not.

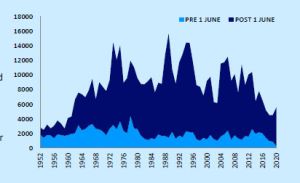

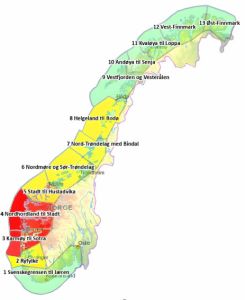

The restraint encouraged onto the salmon farming industry at the beginning of March was the announcement of the latest Traffic Light assessment. The most significant part of the announcement was that two areas PO 3 and PO 4 were classified as red meaning that the overall production must be reduced. This decision came as a surprise because the sea lice Expert Group had recommended that only PO 3 should be classified as red with PO 4 as yellow. The Government also ignored the Expert Group recommendation that PO 9 should be green and classified it as yellow.

The reason for this difference was that the Government decided to base their classification of the 13 production areas on not just the assessment of the 2023 data but also that from 2022. Why they have done this is unclear except possibly to show that they are determined to protect wild salmon, even though anglers across all of Norway are still killing about 64% of the potential breeding fish they catch. I would clarify that my own view is that the real problem for wild salmon occurs out at sea and is not due to the continued exploitation of fish by anglers or commercial netsmen but neither helps in ensuring every wild fish that returns to Norwegian rivers to breed has the opportunity to do so.

Unfortunately, the 2022 data was only published at the same time as that for 2023 so I have not had the chance to delve too deeply into the data, however, the data that I have analysed would suggest that my views of the Traffoc Light System would be no different to those that apply to the 2023 data.

The Sea Lice Steering Group, which consists of three representatives from the Veterinary Institute, Institute of Marine Research and Norwegian Institute for Nature Research write in their report that the mandate of the Expert Group includes details of any uncertainty in their assessment of the state of affairs relating to the years’ monitoring and assess any trends with previous years. However, the descriptions of uncertainty are relatively minor and in my opinion are only expressed because the mandate says they must explain the areas of uncertainty. Unfortunately, I wouldn’t expect the Expert Group to express any significant areas of uncertainty primarily because all of the Expert Group are invested in the science that forms the basis of their assessment. Together, the Expert Group members are named 68 times in the scientific references. If the Steering Group are added to this, then this increases to 75 in total. The Expert Group are never going to suggest there is any major uncertainty in the science because together they created this science. It is their science.

For me the area of uncertainty is extremely clear – it is the whole narrative about the impact of sea lice on wild fish that is uncertain. Perhaps if the Expert Group could demonstrate for example, how the salmon population of the river Etne has been directly impacted by sea lice, rather than some modelled version which bears little resemblance to reality, my uncertainty would be reduced.

I have written previously about the ‘lure of models’ and highly recommend the book Escape from Model Land by Erica Thompsen as essential reading. Her message is that we should all learn to use models more safely and also learn when not to use them, but that we need a healthy respect of the risk of confusing Model Land for the real world. Models have an almost magical capacity to lure their users into mistaking the sharp, tidy analytically accessible world of a model with actual reality. It shouldn’t be beyond the capability of all the scientists in IMR, NINA, SINTEF, VI, and NORCE plus any others to demonstrate real world impacts of sea lice rather than those of models.

I have to admit that I am not a modeller. I prefer to look at real world data and this has formed the basis of my analysis of the NALO sea lice data. In this issue of reLAKSation, I would like to highlight some very basic areas of concern from the 2023 data.

The thirteen production areas that make up the Traffic Light System could be said to be of approximately similar size. Faced with drawing up a research protocol to sample sea lice in these areas, I personally would aim to sample each area a similar number of times using the same methods. I appreciate that the time of fish migration will differ from the north to the south but given different times of sampling, I would expect all thirteen areas to be treated similarly so that they can be effectively compared with each other. I would hope that similar numbers of fish would be examined in each area, although I acknowledge the difficulties in achieving this. However, the future of the salmon farming industry should not depend on the inability of scientists to catch sufficient fish to make a proper assessment.

Unfortunately, the thirteen production areas are not treated the same. Some are sampled at multiple sites and for different lengths of times. Some are sampled using nets whilst others are sampled using traps. There is absolutely no consistency in the approach adopted.

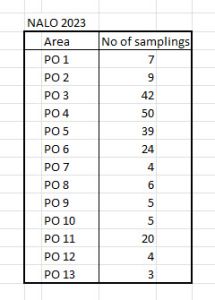

Because multiple locations are sampled, the number of samplings for each production area can be measured in week equivalent samplings. These are shown in the table. It can be seen that in 2023 PO 13 was sampled over 3-week equivalents whilst PO 4 was sampled over 50-week equivalents.

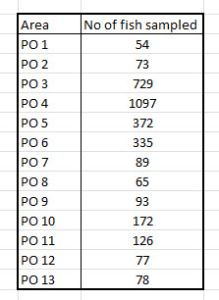

Inevitably, when more samplings are carried out, more fish will be caught (at least in theory) and the theory turns out to be correct. The lowest number of fish caught was just 54 in PO 1 whilst PO 4 was assessed on a catch of 1,097 fish. How can these be considered comparable?

What is of more concern is that the assessment uses Taranger’s formula for estimation of mortality. His 2012 paper recommends that a minimum of 100 fish should be used in the assessment. Yet seven, that is more than half of the production areas, caught numbers of fish that fell well below that recommendation.

This year, as mentioned earlier in this commentary, two of the production areas have been assessed differently in that data from 2022 was also included.

PO 4 was sampled 59 times in 2022 catching 872 fish. That is more sampling effort, but fewer fish caught. In 2022, PO 8 was sampled 3 times, half as many as in 2023 catching 61 fish, four less than in 2023. In 2022, five production areas were assessed on numbers of fish that are below the Taranger’s recommended minimum catch size. It seems that the fate of farmers in PO 8 has been assessed on between just 61 and 65 fish. Is this sufficient basis to determine the fate of such an important industry in Norway?

The Norwegian Fisheries Minister has said that the Traffic Light will ensure predictable and sustainable growth in the aquaculture industry with the colour based on how salmon lice affect wild salmon in each production area.

The question for the Minister is whether the colour is based on a perception of how sea lice affect wild salmon in Norwegian Model Land or on how sea lice really impact wild fish in rivers such as the Etne. Perhaps, there is still a chance to actually find this out, providing the anglers have left any alive.

Regulations? Fish Farmer magazine reported on the Norwegian Seafood Council’s Seafood Summit recently held in London. This was attended by both the Norwegian and British Fisheries Ministers.

In her address to the meeting, Cecilie Myrseth said that the Norwegian Government is now preparing a White Paper on animal welfare including welfare issues for fish. She made it clear that she was proud of the hard work being carried out by Norway’s seafood industry but there was always room for improvement.

She added that the aquaculture industry has challenges which must be resolved. Too many fish die before slaughter. In many cases because laws and regulations are not followed. It is unacceptable. She said that if the industry wants to grow, things must be done properly and according to the regulations. The fish must be taken better care of.

I was at the summit and heard the Minister’s speech and was disappointed by her comments. Perhaps, the Norwegian Government might consider that it is not the farmers who are fault here but rather the regulations. Certainly, in my opinion, the Traffic Light regulation Is not fit for purpose and the repeated treatments required to maintain an abnormally low level of lice is simply resulting in increased mortality. The quickest way to reduce mortality would be to instigate a new debate about sea lice rather than rely on a regulation based on theoretical modelling.