February: Fish Farmer magazine has highlighted that the first phase of the Scottish Environmental Protection Agency’s (SEPA) new Sea Lice Framework begins this month. However, before I discuss this news, I want to consider two articles from two other publications.

The Orcadian newspaper reports that the Orkney Trout Fishing Association (OTFA) has expressed ‘particular concern’ after discovering that sea lice were present on all 23 fish they retrieved from the Bay of Ireland and the outflow from the Loch of Stenness. OTFA were sharing the results of last year’s sweep netting which were intended to help with conservation. Whilst OTFA acknowledge that the sample did not meet the minimum sample size for the national lice monitoring protocol and that it is difficult to make any firm conclusions, they say that the results illustrate the potential magnitude of the lice problem and underline the pressing need to better understand the issue.

Meanwhile, Trout and Salmon magazine includes an eight-page spread about a remarkable year of fishing for sea trout on Orkney’s wild coast. The article was written by Sandy Kerr who is Professor of Marine Resource Management at Heriot -Watt University and is a regular visitor to Orkney to fish for sea trout. The article details his experience of fishing for sea trout over the whole of last year. The article does not mention sea lice nor salmon farming. Instead, he waxes lyrically about the delights of catching this elusive fish. He mentions the Loch of Stenness but points out that it is the sea rather than brackish water lochs where Orcadian anglers seek out the ‘silver’.

One anecdote that Professor Kerr relates is that he asked a local fishing legend what is best for catching sea trout (meaning which fly should he use) to which the reply was a ‘car’. He meant that the fish are never to be found where you think they are and if you’re not catching fish then drive to try somewhere else.

I am always amazed that the angling press is always willing to attack salmon farming for sea lice yet when they publish articles about fishing in the fish farming area, there is never a mention of sea lice nor salmon farming. Equally, if sea lice are such an issue, why are anglers even fishing in the fish farming zone when claims are made that salmon farming has caused local extinction of migratory fish stocks. It seems that they put out a different content to the angling fraternity than they do to the public.

I’ll return to the sea trout of Orkney later.

Meanwhile Fish Farmer magazine continues with the news about the Sea Lice Framework which SEPA describes as a ‘proportionate, evidence-based approach to protect young salmon from sea lice’. The article in Fish Farmer adds that the framework is ‘built on international best practice and using cutting edge science to triage risk’.

SEPA have used an interesting selection of words in their description of the sea lice framework, which are worth further consideration. The first word is proportionate which suggest that the measures adopted are balanced against the risk. The question must be whether the risk to wild fish from sea lice merits the proposed sea lice risk framework. As I have pointed out several times previously, SEPA told the Scottish Parliamentary REC Committee that they did not think that sea lice from farmed fish were responsible for the declines of wild fish populations around Scotland. They added that there are a complex range of reasons for the decline. However, SEPA also said that the issue is whether the state of populations at the moment can be affected by the added pressure of further sea lice as the fish migrate to sea. They ended by saying that the concern is whether the additional pressure of sea lice is now significant as wild stocks are at such low levels.

The simple answer is that the proposed sea lice framework is not proportionate to the risk. As sea lice are not responsible for the declines of wild fish, then even when the stock is small, the risk from sea lice must remain small. We know that the risk is small because the Marine Directorate have assigned Grade 1 and 2 classifications to 33 rivers within the salmon farming area. This means that anglers are able to kill the fish they catch from these rivers subject to local regulations. Clearly, salmon stocks are not under sufficient threat to stop the killing of fish by anglers or close rivers to fishing altogether. The sea lice risk framework is therefore not proportionate but must be considered overly excessive. It could be argued that the only reason there is a sea lice risk framework is because of claims by the wild fish sector that sea lice from salmon farms are responsible for the decline of wild fish, which SEPA have said is not the case.

The next words are ‘evidence-based’. This would seem relatively straight forward in that in order to implement the framework, SEPA will have gathered evidence that sea lice from salmon farms is having a negative impact on wild salmon, irrespective of whether the stock is under excess pressure or not. I have been working on salmon interactions especially in relation to sea lice and I have yet to see any clear-cut evidence that there is an impact on wild salmon population. SEPA has said that sea lice from salmon farms are not responsible for the decline in wild fish so they must have some evidence to support that view. Equally, they must have some evidence if they believe that sea lice from salmon farms are having an impact that requires the need of a sea lice risk framework. I suspect that the truth is that they simply don’t have any evidence at all, regardless of their intention.

The origins of the sea lice risk framework go back to the Salmon Interactions Working Group. Although I wasn’t present, I have copies of all the meeting minutes which includes actions. An important observation of these meetings was the absence of any sea lice specialist – something that runs through a great deal of sea lice research – but more importantly, whilst the group agreed a joint position ‘to acknowledge the potential hazard that farmed salmonid aquaculture presents to wild salmonids and agrees to examine measures to minimize the potential risk’, there was a complete lack of evidence presented to support the view that there was a potential hazard. The only supposed evidence were a couple of papers from Marine Scotland Science, which provided no evidence at all. I have dissected these papers in past issues of reLAKSation and can only conclude that at best any scientific evidence is perceived more than real.

The Marine Directorate and the Crown Estate have been paying the wild fish sector to collect sea lice data from along the west coast. Under FOI they published twenty-three years’ worth of data but to the best of my knowledge, none of this data has been analysed in relation to the presence of local salmon farms. I believe that the data has never really been analysed at all. The identification of some fish with high lice counts appears to be all the evidence that some need as proof of the negative impacts of salmon farming although such observations don’t prove anything at all. Earlier I mentioned that OTFA had acknowledged that their sample size had not been large enough to meet the minimum requirement of the national protocol on sea lice assessment. In fact, when the national data is analysed for the twenty-three years of data published by the Marine Directorate, only 18% of the samples meet the minimum recommended number as established by the same protocol. Of course, as the data has not been properly examined, no-one would know that. Between 2011 and 2015, the Rivers & Fisheries Trusts of Scotland (RAFTS) produced an annual report on the sea lice counts. The reports clearly state that the intention is to present the data not to attempt to draw any conclusions about the impact of aquaculture on wild fish. Presumably this was because they were unable to associate the sea lice counts with local farm activity so could not make any comment.

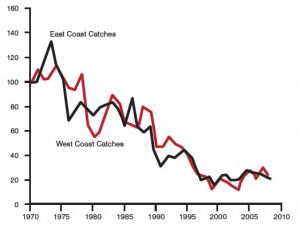

As part of SIWG, Marine Scotland Science were asked to scope the work to undertake comparison of changes in catches of wild salmon between east and west coasts. Whether this work was undertaken is not recorded in the minutes. However, this data was already available, but SIWG opted to refuse the hear any evidence from anyone outside the group, which rather limited the evidence available to them. In addition to my own research, the SSPO had also looked at a comparison of catches and produced this graph.

Sadly, the wild fish sector claimed that this was unrepresentative and that only rod catches should be considered. This blinkered vision is exactly why wild salmon are now in crisis.

Despite the clear message resulting from the findings of my own research, I remain open-minded to receive any other evidence, especially from the wild fish sector. Perhaps their reluctance to discuss the issues is because such evidence doesn’t actually exist.

International best practice is also advanced in relation to the proposed framework. Clearly, the international aspect means Norway. Certainly, SEPA have referred many times to Norwegian research and the fact that Norway has introduced regulation in the form of the Traffic Light System. I recently managed to obtain the sea lice data for 2023 that has been used to assess the risk to salmon in the 13 production areas and if the interpretation of this data is considered best practice, then Scottish salmon farmers should have real concerns. As I am still working on this data, I don’t want to comment too much at the moment. I will openly share my findings once all the work is done.

Cutting edge science is also referenced. I don’t know what this terminology refers to but as I see that sea lice science is divided into two – sea lice science and modelling science, I presume that it is the modelling that is at the cutting edge. However, as I have written before, model world and the real world are not necessarily the same thing. They are very different and if the modelling uses cutting edge science, then the salmon farming industry should be extremely wary. This is because whilst the modelling might involve cutting edge science, the science relating to sea lice is still poorly understood by those claiming salmon farming poses a risk to wild salmon stocks.

Meanwhile, SEPA has published FAQs on Sea Lice Regulatory Framework Implementation. Sadly, this doesn’t instil any confidence in the approach taken. Firstly, SEPA say that they assess the risk to wild salmon through a specially developed purpose-built screening model. However, if SEPA are also looking to build on International Best Practice then they should consider that the Norwegian Traffic Light System uses three separate models (could this be because none offer a truly realistic picture of what is happening to sea lice) and then a panel of ‘experts’ discuss the various findings and agree on a consensus. If Norway cannot rely on one model, can we be sure that SEPA’s version is truly reliable especially as it has not yet been validated.

The SIWG meetings also referred to Taranger’s assessment which is also used in the Norwegian Traffic Light system. Taranger first proposed his assessment in 2012 yet here we are in 2024 and his assessment has also not been validated. It is all still conjecture and this is reflected in some of the results of my own analysis of Norwegian sea lice data.

SEPA asks how will they develop an understanding of risk? Their answer is that in March, salmon farming companies must provide SEPA with information of farmed salmon numbers and average sea lice counts per fish from the last six years and this data will be used to update SEPA’s risk assessments.

To me, this is the greatest puzzle of all. I thought the whole point of the sea lice risk framework was to protect wild salmon so surely what SEPA need to know is data about wild not farmed salmon. To the best of my knowledge, no-one has shown that high sea lice counts on farmed fish can be directly linked to any threat to wild salmon. In fact, analysis of catch data going back many years and the presence of salmon farming has been presented to SEPA as evidence of the lack of harm but they have failed to recognise the relevance. It seems that it is acceptable for SEPA to use historic farm data but not that from the wild. Of course, farm data is much more comprehensive than that produced by the wild sector and also more widely available. The Marine Directorate continue to protect the interest of proprietors over that of wild salmon by withholding catch data from rivers, as opposed to fishery districts. Currently, the absence of this data is the subject of a complaint to the Information Commissioner. This is not the first such complaint because one was submitted when the Marine Directorate tried to reduce the number of reporting fishery districts by half in order to ensure the privacy of proprietors was not invaded, The Marine Directorate lost and we still have the data from 109 districts (or not – see later)

It seems incredible that SEPA have not demanded this data too but then the sea lice risk framework is not really about protecting wild salmon but rather about imposing unnecessary regulation on the salmon farming industry as demanded by the anglers and the NIMBYS.

Before I finish, I would like to return to the subject of Orkney.

The SIWG meeting minutes mention Orkney saying that ‘it was noted that the risk management framework might not suit the needs of Orkney, where sea trout populations are important and do not follow the same migratory behaviour as wild Atlantic salmon.’ This means that the Marine Directorate were aware that sea trout formed all the local catch.

The question is how many sea trout have been caught over the years and how many are caught now so the overall trend can be assessed. Certainly, Prof Kerr records in Trout and Salmon magazine that he caught a fish of 3lb in August last year. As the 2023 catch data is not yet available and unlikely to be for another couple of months, I am unable to ascertain how many trout were caught around Orkney. However, I know that I don’t have to wait until late March or early April for the findings because anyone consulting the official Scottish Government catch data will find Orkney is missing from the spreadsheet even though Orkney is a recognised fishery district (number 109). Why Orkney is missing from the data set should be a mystery, but it isn’t. When I began to analyse catch data. Orkney was included and I have the data from 1952 to at least 2014. In all that time, there was only one record of a sea trout catch from the islands. That was in the early 1960s and amounted to 36 fish. Every other year is recorded as zero.

Is lack of data because no-one caught any fish or because they never reported the catch to the Marine Directorate. I cannot answer that. What I can say is that the OTFA have a website https://orkneytroutfishing.co.uk/ in which they say that they are dedicated to the preservation and enhancement of game fishing throughout the Orkney Islands. They have a page about sea trout fishing https://orkneytroutfishing.co.uk/fishing/f_seatrout.html with pictures of sea trout that have been caught so clearly there is a sea trout catch from the Orkneys. What the website does not include is any details of annual sea trout catches so seemingly, whilst OTFA are concerned about the impacts of sea lice on local sea trout, they don’t have any evidence at all to the point it seems that there is no official record of catches.

I suspect that scientists are too busy refining their models to bother asking why.