Mixed up (genes): Sciencenorway.no reported that the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research (NINA) and the Institute of Marine Research (IMR) have said that there is a considerable amount of interbreeding between escaped farmed salmon and various wild salmon stocks, which could have serious repercussions for wild salmon populations. The two institutes have examined 250 different salmon stocks and found significant genetic change in 31% of the populations.

Kjetil Hindar, a senior researcher at NINA said that the consequences for wild salmon are that interbreeding with farmed salmon makes them les adapted to nature. ‘We have conducted several experiments and found that the offspring of farmed salmon generally have lower survival rates.’

The researchers also found that the fish grow faster in freshwater, migrate to sea earlier, grow quicker in the ocean and return to rivers at a younger age. Their life cycle has sped up, so they return to rivers slightly smaller than wild salmon. As wild salmon already face other threats, being less genetically adapted can make it worse for the fish. Kjetil Hindar suggests that if wild salmon are to have a future, then salmon farming must shift to closed containment.

Regular readers of reLAKSation may remember that I have not been particularly impressed with some of the output from researchers at these institutions with regard to sea lice. This latest study does not instil any more confidence in the report.

It seems that I am not alone in having a different view of so-called genetic changes. Fisheries expert Gunnar Davidsson, Head of Resource Management in Tromsø municipality wrote in the Christmas edition of the Icelandic fish and seafood journal – Fiskifretta – that the claims by environmentalists and others about escaped salmon have not been materially proved by research. According to Fish Farmer magazine, Gunnar Davidsson agrees that some Norwegian rivers may be home to too many escaped salmon but that scientific research has not yet proved that these fish have had a permanent harmful effect on wild salmon. He pointed out that overfishing and the impact of power plants has wiped out stocks in some places causing much more damage than by farming.

In Iceland, the propaganda machine of influential anglers and landowners is very powerful and as most Icelanders have little to do with salmon, there is little rebuttal. In Norway, salmon farming is important to the local economy and the discussion is better informed. The reality is that escapes are much less frequent and consequently there are fewer farmed fish in the rivers with much less potential for any negative impacts.

Gunnar Davidsson is not the only one to express an opinion. Aquablogg.no reports that the wording on the press releases in support of this study are designed to give the impression that fast-growing hybrid fry out-compete the wild fry but rather the opposite is happening, and it is any hybrid fry that are being out-competed so that as Gunnar Davidsson indicated, the number of hybrid fry is decreasing year by year. Fewer hybrids survive to reach later stages of development including to the smolt stage. Any hybrids that do become smolts and head out to sea also have a lower survival than the wild fish. Aquablogg.no says the point is that hybrid fish are less adapted to life in the wild due to natural selection. This will weed out variants that could be disadvantageous leaving the wild salmon in a much stronger genetic position.

Aquablogg.no writes that Kjetil Hindar belongs to a group that still believes that each river harbours a distinctly genetically different salmon population. The reality is that wild salmon wander between rivers, remaining to breed. This is how the salmon gene pool is strengthened, not weakened. I have written previously of the 2012 £1 million FASMOP study that was supposed to identify genetic differences between salmon from different rivers. The fact that FASMOP is now never discussed (except in reLAKSation commentaries) shows that the wild fish sector would consider the project to be best forgotten.

Aquablogg.no writes a much more detailed account of hybridisation between farmed and wild salmon for those with more interest in the subject.

For me, the whole issue of negative genetic introgression makes little sense. For many years, it has been argued that hybrids of farmed and wild salmon are inferior to wild salmon. If this is true, then Darwinian evolution will prevail, and these inferior fish will simply not survive.

Finally, it should also be remembered that the measure of genetic introgression is through genetic markers rather than in the genes. Genetic markers are also the way we humans can trace our ancestry. Just because we have markers for different ethnic groups, does not mean that we actually behave like any of them.

Ailort: A recent edition of Trout and Salmon magazine included a long article about the impacts of predation of wild salmon. The article argued that all the predators thought to have an impact on wild salmon don’t. The theory, using the Rier Tyne as an example, is that 57 million baby salmon emerge from eggs each spring are reduced to 600,000 smolts that leave the river. The article says that ‘anyone who thinks the death of at least 56 million fish is due to predation cannot do maths.’ Instead, the deaths are blamed on starvation. Whether this is correct is open to debate. The article makes an interesting case.

However, the author of the four-page article also included one line that stated: Under 5% of two-year-old salmon smolts return as adult fish to breed (much less on the west coast due to sea lice pollution).

The publication of this article led to some correspondence with the author who sent the draft of another yet unpublished article about salmon farming. This article mentioned that the river Ailort and the freshwater loch Eilt was once a world-famous sea trout fishery but the sea trout there had suffered a catastrophic impact from sea lice so that within a few seasons, the species had become locally extinct.

I would like to point out that any data referenced here is not my data. It all comes from the wild fish sector and the Scottish Government’s Marine Directorate and is available from the relevant websites. Anyone can use the same data to draw the graphs reproduced here.

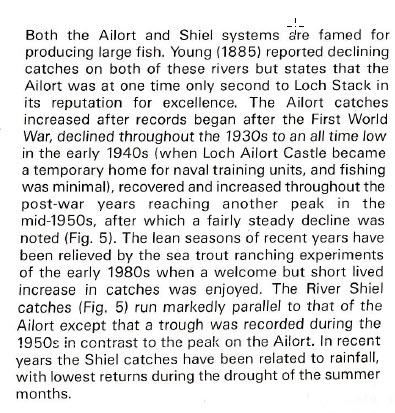

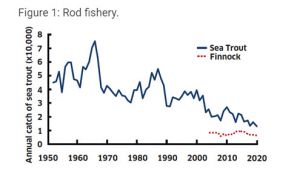

The adjacent loch to the river Ailort is where Unilever stocked the first smolts in 1967. The following graph is the official sea trout catch from the Ailort fishery district from 1952 to present. The fishery collapsed in the late 1980s but from the late 1960s until then sea trout catches remained relatively stable.

However, the fishery had declined from when records first began in 1952 until the late 1960s. This was in part due to the disease UDN and the associated reduction in fishing effort due to the closure of many fisheries to combat the disease.

This decline of sea trout catches during the 1950s was mirrored across the whole of the west coast.

In 1982, which is the middle of this graph, farmed salmon production had reached just one thousand tonnes. The steep decline from 1952 to the mid-1970s had nothing to do with salmon farming. One of the pioneering farmers had always claimed that sea lice were never an issue until the late 1980s. I was working in fish healthcare at the time, and lice were very low on my agenda.

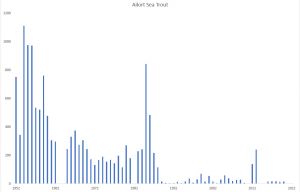

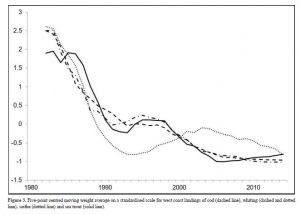

The unpublished article states that Loch Eilt was a famous sea trout fishery. In 1987, a symposium about sea trout was hosted by the Scottish Marine Biological Association. The subsequent report includes reference to Ailort.

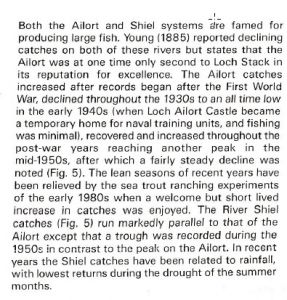

The report also includes a graph of catches:

Salmon farming was still very much in its infancy at the period towards the end of this graph.

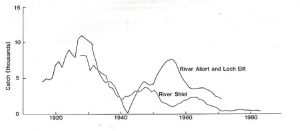

The symposium report also included a graph of the Loch Stack fishery which was arguably more famous than the river Ailort.

The period covered by this graph was prior to the arrival of salmon farming anywhere in the vicinity.

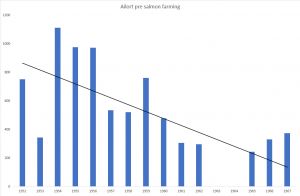

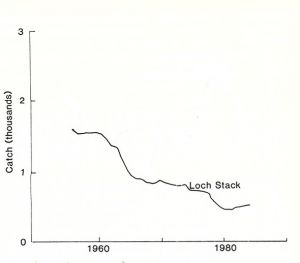

So why did the Ailort fishery district sea trout stock collapse in the late 1980s? In their paper about Loch Maree, Butler and Walker said that the only change to happen was the arrival of salmon farming. However, this is untrue. In 1984, under pressure from commercial fishermen, the Government removed the three-mile fishing limit allowing trawlers to fish inshore including inside many west coast sea lochs. The subsequent collapse of marine fish stocks is well-documented but never compared to collapse of sea trout.

The following graph shows the pattern of decline of cod, saithe and whiting. The black line is sea trout.

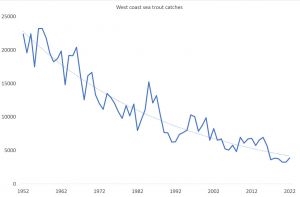

The unpublished article also states that any suggestion that the decline of sea trout on the west coast was an unfortunate coincidence with a natural population decline is refuted by the fact that local sea trout populations have become functionally extinct wherever salmon farming has taken place throughout the west coast. In contrast the article says that sea trout populations remain robust in eastern Scotland where there is no salmon farming.

Yet, the Marine Directorate’s record of sea trout catches across Scotland tell a very different story.

Although, claims of near extinction have been made for sea trout on Scotland’s west coast, anglers fishing rivers in the salmon farming area have still managed to catch a total of 87,970 sea trout over the last ten years (from 2013) of which 6,681 were killed and kept by the angler.

Lots of claims are made against the salmon farming industry which are repeated in the media. However, when such claims are investigated, a totally different picture emerges. Its no wonder that groups like Wild Fish refuse to discuss their claims.

Scrutiny?: The Strathspey and Badenoch Herald reported that the Scottish Parliamentary Rural Affairs Committee recently scrutinised the proposed changes to protection for wild salmon. Scottish Greens MSP Ariane Burgess, who sits on the committee has warned that urgent action is now needed to save Scotland’s wild salmon from extinction. However, in my opinion, if salmon must depend on the Scottish Green’s for protection, then their road to extinction will be assured.

Ms Burgess has said that 65% of Scotland’s iconic salmon stocks have been assessed to be in poor conservation but as I wrote in reLAKSation no 1159, this is just nonsense. She also says that a consultation on the changes found most respondents want urgent action to be taken on the other pressures on wild salmon including fish farming, habitat degradation and pollution. She added that salmon farms impact on wild salmon through the spread of sea lice, chemical pollution and inter breeding. Exploitation, including angling, is not included in the list of concerns which isn’t surprising given that most respondents were anglers. Ms Burgess told the newspaper that she is clear that angling is not a primary cause of wild salmon decline but since these changes will allow increased catching and retention of wild salmon in seven rivers, it is even more important that we act on the primary pressures affecting wild salmon populations including fish farming. Obviously, the fact that anglers have caught and killed around 5.9 million wild fish since records began is not seen as a primary pressure.

She attributes the deaths of 71,000 wild salmon every year to salmon farming. Even if as a rough guide, this number was the same every year over the last 40 years, then salmon farming would have killed 2.8 million salmon, which is less than half that killed by anglers that we know of. Of course, by the end of the 1980s, salmon production was only 28,000 tonnes so a fraction of what it is today and thus, the impact, if the claims of Ms Burgess were accepted, then the impact would be much less than 71,000 fish. The estimated figure, according to Ms Burgess’s thinking would be probably not more than 1 million deaths, a sixth of those killed by anglers.

However, the figure of 71,000 has no real basis in reality. The figure appears in a report by Just Economics and clearly, if anyone wants to know the impacts of salmon farming, a group of economists would not be the most obvious people to ask. In fact, anyone reading the detail of the report, would know immediately that their numbers are flawed.

The Just Economics report commissioned by Changing Markets; an organisation not known to be sympathetic to salmon farming, states:

The total rod catch for 2018 was the lowest on record and under 50% of the average of the period 2000-09. Rod catches are only part of the story and there is a similar finding for returning salmon, the stocks of which have more than halved in the 20 years to 2016 to just over a quarter of a million, As with our Norwegian estimates, if we assume 20% of these are due to salmon farming impacts we arrive at an estimate of 71,000 wild salmon being lost to fish farming each year.

Just Economics don’t reveal the source of this information but according to the Marine Directorate graph, the returns for 2016 were well above quarter of a million fish. Equally, if 71,000 fish are 20%, then in 1996, the number returning would have been 355,000 fish.

However, of more interest, Just Economics refer to their Norwegian estimate. The report states:

“Impacts on escaped salmon are difficult to model but it is estimated that lice from salmon farms kill 50,000 wild salmon per year.162 We know that returning salmon are about half a million fewer than in the 1980s. If we conservatively assume about 150,000 of these are because of salmon farming (we know 50,000 are due to lice infestations and assume 75,000 are due to hybridisation and 25,000 due to infectious diseases). This is about 30% of the lost wild salmon population.”

Without questioning the actual assumed numbers, the glaring error is that Norwegian mortality from salmon farming is estimated at 30% of lost wild salmon, yet Just Economics say that as with Norway estimates, we assume 20% of lost fish are due to salmon farming.

Just Economics make a lot of assumptions in their report. Ariane Burgess should not assume that just because the report comes with an impressive title that the assumptions it makes are anywhere near the truth.

The article finishes off with a quote from Wild Fish. Who say that everywhere in the world which has seen the growth of intensive salmon farming has also experienced a collapse of wild salmon runs. It wasn’t that long ago when the organisation updated the RAFTS graph showing that east coast catches had increased which was attributed to the absence of salmon farms. The east coast is still free of salmon farms, yet catches are near to record lows. At the same time, Spain, France, and other parts of Europe which do not farm salmon have also seen their salmon stocks head towards extinction.