Unplanned: In his review of the aquaculture regulation process, Professor Griggs had said that he had never come across such a degree of mistrust, dislike, and vitriol at both an institutional and personal level between the industry (mainly finfish), certain regulators, parts of the Scottish Government and other stakeholders and he said that this makes current working relationships very challenging.

If there was an example of the need for change than it could be seen in the Highland Council Planning Committee meeting that took place on 15th June (https://highland.public-i.tv/core/portal/webcast_interactive/667938). The meeting included an application from the salmon farming company Mowi to alter their farm at Loch Hourn by replacing the existing pens with fewer larger pens. The farm was originally established in 1990 and according to the Press & Journal, has a strong environmental record which meets RSPCA standards. It appears that the existing regulators had no objections to the changes, yet the application was rejected.

The refusal came about after one councillor introduced an amendment to reject the application. The main reason given was that over the period of 25 years that the farm has been in operation, it is acknowledged that populations of salmon and sea trout have diminished. The councillor believed that the extra biomass that the farm will add to the cumulative effect on wild salmon.

Another councillor stressed similar concerns and highlighted a submission from the Friends of Loch Hourn, (FOLH) a group that was formed in 2020, primarily it seems to oppose any further salmon farm development in the loch. The group is part of the Coastal Communities Network, that I mentioned in the last issue of reLAKSation, and who are not interested in hearing anything about salmon farming that might undermine their established narrative. Unlike some member groups of CCN, FOLH have a website in which it is clear that they opposed the Mowi application (https://www.friendsoflochhourn.org.uk/).

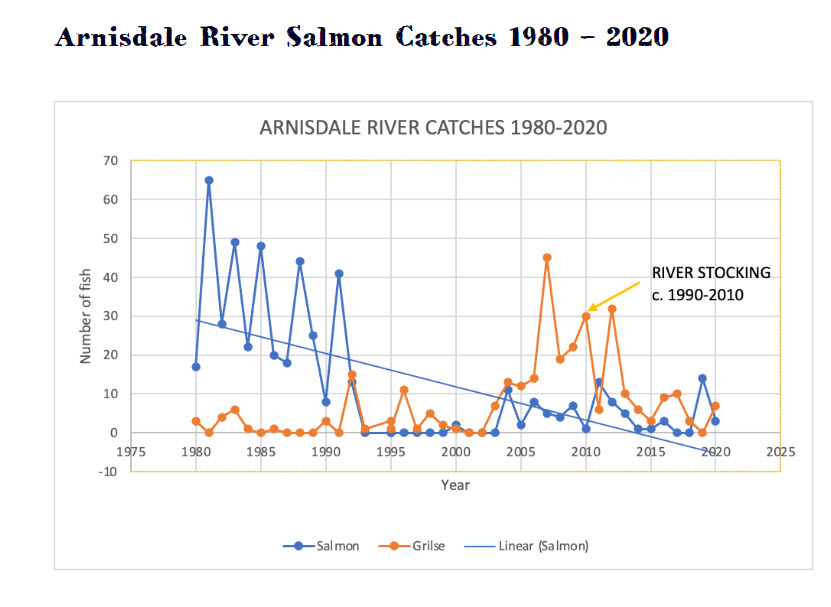

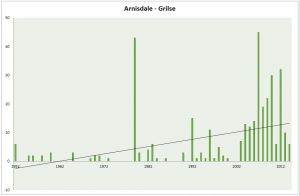

FOLH cover a number of issues but I was immediately attracted to their graph of salmon catches from the local River Arnisdale, dated from 1980. They say that this shows salmon numbers have dropped significantly during this period. They say that this is especially noticeable after 1990, which is when the farm was established (and that seems to be all the evidence that they can come up with to show salmon farms are killing wild fish in Loch Hourn). On a separate issue, it is interesting to note that grilse catches picked up after a restocking programme was introduced at about the same time the farm arrived. Perhaps, the sea lice that FOLH blame on the decline of wild salmon didn’t like to attack fish that had been restocked?

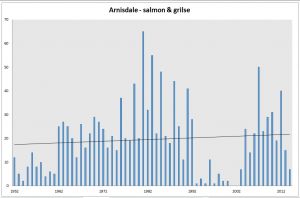

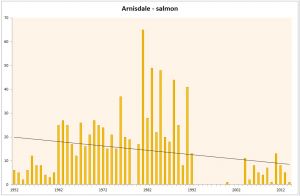

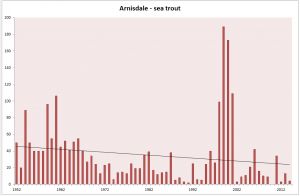

By 2015, I had managed to obtain all the catch data from 1952 and unlike anyone else, had produced trend graphs for all 109 fishery districts for salmon, grilse, salmon & grilse and sea trout. The much longer time scale allows for a better understanding of the trends rather than focussing on a specific time associated with the arrival of a specific farm.

What these graphs tell us is that overall, catches of salmon & grilse (blue) from the Arnisdale have increased over the sixty plus years since records began. There is a gap during the 1990s when catches appear to have collapsed and which the wild fish sector associate with the growth of salmon farms. Whilst FOLH say that this collapse is linked to the arrival of the local farm, the reality is that this dip in catches occurred across the whole of the west coast. At the time there was no measure of angling effort, but the likelihood is that catches declined because anglers were being bombarded with messages that salmon farming had killed all the fish on the west coast and stocks were near extinction. Clearly, anglers hoping to catch a fish went elsewhere. However, the brave few who continued to fish found good catches and word spread so that by the end of the 1990s anglers had returned to the area in numbers and catches recovered. If the farm was killing wild fish why did catches recover to near previous numbers?

When separated, salmon and grilse catches appear to be on very different trajectories. This Is not of any surprise as I have previously written that salmon catches were in long term decline across all of Scotland, not just the west coast, whilst grisle catches increased. This was part of a pattern of long- term trend observed on the river Tweed and which I applied to the west coast in my most recent peer-reviewed paper.

Finally, sea trout have been in decline across the west coast from 1952, long before salmon farming arrived. I am still waiting for anyone from the wild fish sector to explain how salmon farming has decimated sea trout stocks when they had already been in decline for over thirty years.

Meanwhile, FOLH have posted the views of a local fisherman as to the decline of wild salmon and sea trout. This unnamed fisherman, currently catching prawns says that:

“The most obvious damage has been to the local salmon and sea trout populations. It was common to see salmon and sea trout jumping in front of the house; now there are never salmon to be seen and the sea trout maybe a handful of times a year.

Back then if you put out a net, which one really shouldn’t have done, you would quickly catch a salmon or a sea trout for the pot. ‘Kenny Salmon’ even has a commercial netting station across the sound at Isle Ornsay but all that has long gone. It is undeniable that up and down the west coast, wild salmon populations have been virtually destroyed, yet the salmon industry seeks to expand with ‘modelling’ and ‘Environmental Impact Assessments’ that try to pretend that nothing bad is happening here.”

So, salmon farms are using modelling to demonstrate their lack of impact. Yet seemingly, FOLH have commissioned modelling of sea lice dispersion to demonstrate that there is an impact. FOLH have produced an eight- page summary of the sixty-one-page report from MTS-CFD Ltd.

The executive Summary begins by stating that ‘the correlation between salmon farms, sea lice and the decline in wild salmonids is well established in the scientific literature’ which is news to me. I appreciate that I am only in my twelfth year of research on this subject, but I am unaware of any scientific literature that established any correlation between wild salmon declines, sea lice and salmon farms. It is only in the body of the report that the relevant scientific literature is revealed and that is the Summary of Science posted on the Scottish Government website. The papers claimed to show such a correlation cited in the summary, don’t show any such correlation at all. I am still waiting for an explanation why these papers are even cited in the summary. Any correlation is about as strong as the narrative given by the fishermen above. There used to be wild fish and now there aren’t. There used to be no salmon farm and now there is!

LOFH state that modelling of sea lice on wild fish is one of the most accurate ways to assess the risk of harm. However, the modelling is theoretical and there is no evidence that larval lice act in the way predicted. In fact, a paper from Canada, which is largely ignored because it doesn’t support the accepted narrative clearly showed that larval sea lice remained in the vicinity of salmon pens, where there is vast source of potential hosts.

LOFH say that that any expansion of salmon farming comes with costs but the loss of our wild salmon and sea trout would be one of the worst environmental outcomes. It is therefore surprising that LOFH have not expressed any concern about any other impacts on wild fish. Since the farm was established, anglers have caught and killed 139 salmon and grilse and 739 sea trout. Since records began in 1952 the numbers killed are 984 salmon and grilse and 2,049 sea trout and this is from a river that has a total annual catch of about 30-40 salmon a year. Perhaps, the Highland councillors who are worried about the future stocks of wild salmonids should look towards the impacts of angling rather than salmon farming because we know that these fish are dead, whilst it is only conjecture that salmon farming is killing these wild fish. I would argue that they are not, but sadly, the wild fish sector refuses to engage in any such discussion.

Finally, I was interested to find out more about salmon fishing in the Arnisdale river so I looked in the angler’s bible – Rivers and Lochs of Scotland by the late Bruce Sandison – but it is not mentioned at all. However, the river is mentioned in the 1981 book Salmon Rivers of Scotland by Derek Mills and Neil Graesser. It seems that then, the proprietor of the river did not let out the fishing except to locals in his absence. This is maybe why Bruce does not include the river in his book. Mills & Graesser say that fish rarely enter the river before June but there is a good head of fish from then on as long as there has been sufficient rain. I also have a copy of Salmon Rivers of Scotland by Augustus Bramble first published in 1899 but my edition is dated 1913. Back then, fishing on the Arnisdale was preserved strictly for family and friends.

It seems nothing much has changed with locals, supported by the councillors, wanting to keep the area for themselves. It certainly doesn’t seem that wild salmon and sea trout are the real reason for the rejection, just an excuse.

NASCO: A blog on the Salmon & Trout Conservation website asks whether the North Atlantic Salmon Conservation Organisation (NASCO) is a relevant force in salmon conservation. This is because NASCO are to undergo an external review to see if changes are required in the way the organisation operates. The blog states this is necessary because if NASCO fails to modernise it will become irrelevant in the world of wild salmon conservation.

The problem is perceived to be that politicians from the member countries tend to support activities that jeopardise the existence of wild fish such as salmon farming, agriculture, hydropower, water abstraction, and anyone else who has the potential to pollute salmon habitats. In doing so they ignore NASCO agreements where they threaten the countries’ interests. The blog continues that politicians lack the commitment or integrity to do the right thing. They refuse to stand up to the vested interests of those whose activities threaten wild fish and their waters. I couldn’t agree more.

Scotland should follow the example of Ireland and Norway and close rivers to fishing if stocks are so threatened. Of course, a blog on the S&TC website is going to blame everyone and anyone other than anglers for the problems of wild fish. As I have written before, is it wild fish that are threatened or wild fisheries?

Only a few weeks ago, Alan Wells, head of Fisheries Management Scotland issued a ‘Call for Action’ to help wild salmon. This including lobbying the Government to control the fish farming industry, review the regulation of hydropower, deliver a policy on fish eating birds, introduce methods to prevent seals coming into rivers, help fund habitat restoration and incentivise tree planting.

However, it seems that FMS members also heard the call. A tweet from the Tay Salmon Fisheries Board stated that ‘we are only two thirds through the month of June, but River Tay catches have already surpassed June 2021. So long as decent fishing condition prevails, we could be looking at a good June.’

By comparison, a tweet from a Professor of fish biology in Norway stated that ‘River Teno/Tana/Deatnu totally quiet in late June. Second year with a total ban on salmon fishing. Culturally, socially, economically a disaster. Ecologically a right decision because of the poor salmon stock status. Hoping for a brighter future.’

Poached: The Press & Journal reported that police wildlife officers are encouraging the public to be aware of fish poaching as numbers of wild salmon have reached a critical level. Fisheries Management Scotland added that fish poaching is widespread and highly damaging. They say that ‘Returning adult salmon have already successfully negotiated a range of challenges at sea and any loss of these precious wild fish to illegal activity is tragic and reduced the chances of sustaining Scotland’s salmon populations into the future.’

I would ask what is the difference if that statement is slightly rewritten to say? :-

‘Returning adult salmon have already successfully negotiated a range of challenges at sea and any loss of these precious wild fish to legal activity is tragic and reduced the chances of sustaining Scotland’s salmon populations into the future.’

Surely a dead or damaged salmon is a dead or damaged salmon irrespective of whether someone has paid to fish or not? Why does paying a proprietor with a heritable right to fish make everything alright? When such heritable rights were issued, salmon stocks were plentiful. Perhaps, the time has come to ask whether they are now relevant as salmon continue to disappear from Scottish rivers?