Corrections: Unfortunately, reLAKSation no 1071 suffered from a typographical error. My comment about the River South Esk sea trout catches falling to 10,198 in number in 2020 should have read just 198. The numerical 10 was originally written as part of the next sentence about the ten-year catch average but for some reason found its way in front of the 2020 catch figures. My apologies.

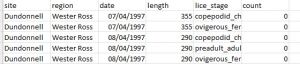

However, that typographical error pales somewhat when compared to an error in some of my aggregated distribution graphs drawn from the official Scottish sea trout data. This was due to the way that Marine Scotland Science had presented the published data. The fisheries trusts had recorded three different lice life stages for every fish they caught. MSS opted to present this data over three rows of the spreadsheet but without any explanation. This led to the conclusion that there were three times as many fish sampled than actually were. Thus, instead of 65,000 sea trout sampled in Scotland between 1997 and 2019, there were just over 21,000. This only became apparent when I dug deeper into the data and found that I couldn’t resolve the numbers. I informed MSS and they admitted that a column with a fish id was missing. This has now been corrected and in addition, a new spreadsheet with the data in a much clearer format has been added to the website.

As a consequence of this error, I have now recalculated the sea lice distribution for each of the graphs I have previously posted. The following two graphs are for the whole data set. The first is the original that used 65,000 records and the second one is the recalculation.

As can be seen there are slight differences in the numbers, but the overall distribution remains the same with the majority of fish sampled carrying no or few sea lice. By comparison, those fish carrying many lice are few in number. This pattern is the same whether the data originates in Canada, Norway, or Scotland or whether the fish is salmon or sea trout. This is because this is the natural distribution pattern for parasites and is exactly what would be expected to be seen. Unfortunately, there seems to be a significant number of people from the wild fish sector, including some scientists, who seem unable to get to grips with the idea of an aggregated distribution. A typical comment appears to be that the reason why so few fish with high numbers of sea lice are caught is because the fish have either died or returned to freshwater, yet fish with high lice numbers are caught that are clearly not moribund or making any effort to return to freshwater.

This lack of understanding of aggregation has prompted me to write a review of parasite distribution, which I will include in a forthcoming issue of reLAKSation. This may be helpful to the wild fish sector who promote a narrative that that the only reason why there are few fish with high numbers of sea lice is because the fish must have died and not because parasite biology tells us a very different story.

Lochaber: At the beginning of the year, The Sunday Times published an article titled ‘Where did all the wild salmon go?‘ Unfortunately, the article did not answer that question but still managed to point the finger at salmon farming. This ignores that fact that salmon farming operates on just one part of the Scottish coast whilst wild salmon are in decline everywhere.

At the time of publication, I commented on the article’s reference to Lucy Ballantyne of the Lochaber Fisheries Trust who had calculated that up to 85% of juvenile ocean bound wild salmon perished in 2021 because of sea lice. She told the newspaper that she had cried over the status of the fish because of sea lice infestation.

However, what is enough to make anyone cry is the total unwillingness of anyone from the wild fish sector to discuss the issues, except with those who agree with them or don’t have any the knowledge of the issues and that seems to include some close to Scottish Government. Their narrative that sea lice are responsible for the demise of wild fish is just a convenient excuse to avoid exploring the wilder issues.

I mention the Sunday Times articles and the alleged level of mortality again because totally by accident I came across the fishery trust sampling data for 2021 on the Fisheries Management Scotland website. The accessibility of this data is not what one would call obvious. In total there are 19 pages of sea trout sampling data (and it does seem that each fish has its own line on the spreadsheet).

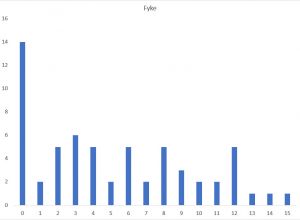

The data from the Camas Na Gaul site in Lochaber has been collected using both seine net and fyke net. The trust has been trialling the fyke net because it is supposed to be more effective, although on one occasion just one fish was caught. The trust sampled using the fyke net on a total of 13 occasions whilst the seine net was used ten times. By comparison, most other sites elsewhere were sampled two or three times.

In total, Lochaber Fisheries Trust caught 431 fish using both types of nets. There were a range of sample sizes from just one fish upwards. The size of the sample is important because small samples may not be reflective of the actual population.

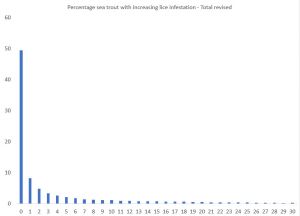

When the increasing level of sea lice infestation is plotted for fish number (or percentage of total fish number) the resulting graph was as follows:

This may not be the smoothest aggregated distribution graph (due to the relatively small sample size) but clearly this is yet another example of an aggregated distribution.

Lucy Ballantyne told the Sunday Times that she has netted some young wild salmon that have more than 150 lice feeding on them and 13 is enough to kill a fish. In fact, the 2021 data shows 12 fish were caught with lice infestations of above 150. These lice were mainly copepods and not the large mobile stages which are those recorded as having a potentially harmful impact above 13 fish. Of the 431 fish sampled, only 59 fish (14%) had 13 or more mobile sea lice. How this equates to 85% mortality is unclear.

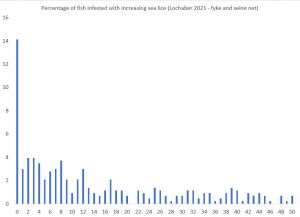

The Fisheries Management Scotland website says that fyke nets are being trialled because they can catch salmon as well as sea trout and can be used in places that are not suitable for seining. They also say that fyke nets provide a more representative sample of the local population.

The graph on the left is from the seine netting and the one on the right is from the fyke net.

Given the small numbers, the distribution is fairly consistent from both methods of capture and yet again, both are aggregated.

It’s a real puzzle that sea trout have been sampled since 1997 and this type of graph has never been promoted but then, this aggregated distribution does not support the claims of damage caused by sea lice from salmon farms so why would anyone sampling infested sea trout ever plot the data this way.

Tórshaven: Fish Farming Expert report that the first sea lice conference for four years will take place in Tórshaven in the Faroe Islands next week. It will be an interesting week but sadly, I will not be attending this time due to other commitments.

A couple of speakers from the UK are highlighted who will be attending the event. One is Dr Sandy Murray of the Fish Health and Welfare Group at Marine Scotland Science. His presentation is called ‘Developing a framework for assessing spatial and temporal variation in parasite density in Scottish waters – implications for wild salmon smolt migration.’

Fish Farming Expert mentions that Dr Murray is the lead author of the paper about modelling tools for assessing interactions on wild salmonids which was published in March last year. A link to the paper’s abstract is provided by Fish Farming Expert. This lists the highlights of the paper which begin ‘sea lice are a major problem for wild salmonid fish’.

Yet the paper doesn’t actually state that sea lice are a major problem for wild fish. It just says that sea lice can reduce wild populations of salmon and sea trout if lice are not controlled on farms, citing the Taranger and Vollset papers as the source. To date, neither of these authors has been willing to explain how their findings of risk can be reconciled with the aggregated distributions that I have highlighted.

What is also interesting is that there is no reference in the paper to one published twenty years ago by the lead author. This was an investigation of sea lice distribution prompted by claims that sea lice are associated with recent declines of sea trout. Although the author had access to various sampling data, there appears to have been no attempt to relate the numbers of host fish with increasing levels of infestation. When reviewing the literature, the paper states:

“Parasites do not affect all individual hosts equally. Even if infection events were fully independent, different individuals would still have different loads, according to the Poisson distribution. However few parasites have such distributions; for most parasites a few hosts have large numbers of parasites, but most have low or zero parasite loads. This is referred to as an over-dispersed or aggregated distribution.”

Yet, this explanation of sea lice loading seems to have been forgotten and instead, Dr Murray is now focussed on a risk-based framework which Marine Scotland Science seem intent on imposing on the salmon farming industry through SEPA even though the evidence that sea lice from salmon farming is damaging to wild fish populations is rather thin on the ground.

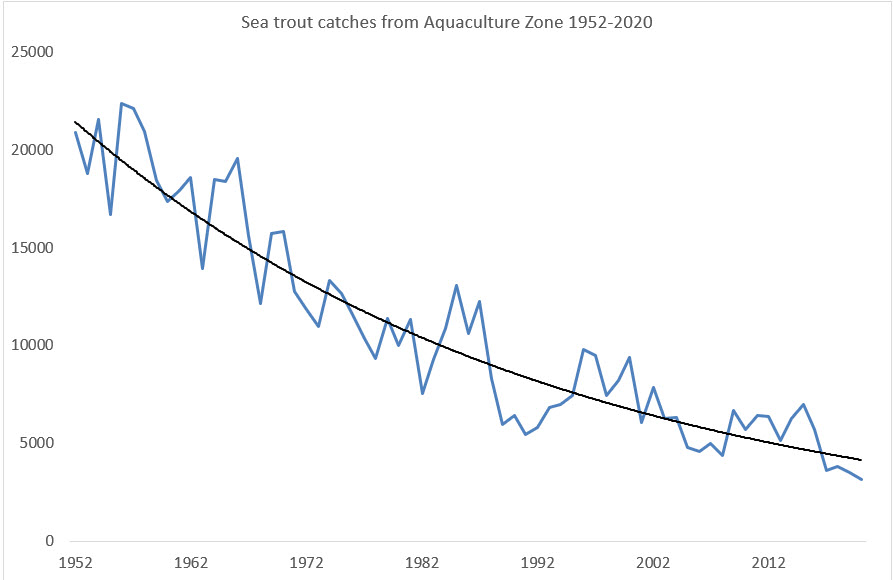

I am still waiting for anyone from the wild fish sector including Marine Scotland Science to explain how sea lice and salmon farming are responsible for the declines of sea trout numbers when west coast sea trout catches had been in decline for thirty years before salmon farming had become established.

This is exactly why we need an independent scientific panel to assess the impacts of salmon farming, not the same scientists who are also undertaking the ‘research’ and who are never going to admit that their own conclusions might be wrong.

Feeding a narrative: A couple of months ago, the Guardian newspaper reported about a new paper that alleged that wild fish stocks are squandered to feed farmed salmon. The paper was co-authored by a member of the NGO Feedback who campaign about food waste. I have written about aspects of the forthcoming paper in the next issue of Fish Farmer magazine which is due out shortly.

The Guardian has now published an article about the growing scandal of fish waste, especially fish caught from the wild. Interestingly, Feedback don’t appear to have made any comment about this form of wastage and neither has Changing Markets, another NGO who criticise the salmon farming industry for their use of fishmeal.

The article highlights that 35% of the fish and seafood harvested are wasted before they ever reach a plate. In part, this is because of the highly perishable and fragile nature of fish which makes them vulnerable to waste especially where there is no facility for cooling. The UN’s Food & Agriculture Organisation say that this waste is increasingly on the radar of regulators because of the need to ensure that any fish is actually consumed and not wasted.

According to the Guardian, the narrative has been that we must produce more food to feed an increasing population but preventing waste would have more impact. There are many reasons for losses and wastage depending on where the fish are in the world. However, one of the biggest culprits are retailers and consumers in middle and high-income countries. Certainly, one of the reasons why we have lost so many fish counters in the UK is that the retailers finally recognised that much of the fish was wasted because it remained unsold.

The NGOs criticise salmon farms because they argue that the fish used in fishmeal should be eaten directly. This is easier said than done given the eating quality of many of these forage fish. Yet, salmon farmers are increasingly using fishmeal made from fish processing waste. At present a lot of this waste does not make it to reduction simply because of the lack of a proper infrastructure to collect all waste produced.

We also need to be better at persuading consumers to eat more, and different fish and also to value it. Unfortunately, we have lost the capacity to market fish due to the decision by Seafish to divert resources elsewhere. This has the potential to increase wastage, not reduce it, as unattractive fish get ignored in favour of the popular species.

As an industry we need to do more, and we should be driving the reduction of wastage and in doing so showing the NGOS that their voice, attacking salmon farming, is being wasted too.