How much more?: I recognise that this commentary is going to elicit the usual range of comments I receive on a weekly basis from the keyboard warriors and industry critics that I’m devious, an idiot, stupid, thick, as well as being an apologist, let alone that I have manipulated the data, misdirected evidence and peddled fallacies. The reality is that these salmon farming industry critics don’t seem to like it when I offer new evidence that salmon farming is not responsible for the disappearance of wild salmon and sea trout.

In this commentary, I am going to present new evidence. However, I want to be clear, this is not my data. It is data collected by the west coast fishery trusts that is processed by Fisheries Management Scotland and submitted to Marine Scotland Science. All I have done is to take the spreadsheet and using MS Excel, sorted the data from low to high. For me. the big puzzle is why no-one else has ever bothered to do the same.

I would however like to begin at the beginning. The recent Sunday Times article, featuring Lucy Ballantyne of Lochaber Fisheries Trusts and her claim that 85% of the smolt run would die because of sea lice, prompted one of my correspondents to take a look at the Lochaber Fisheries Trust website. My correspondent was intrigued by the observation there that detailed sea lice infestations of wild sea trout appear to be higher in the second year of a salmon farm production cycle.

I was asked if fallowing a site would affect the length of the cycle to which I admitted that I didn’t know the answer. What I did have though was five years of sampling data from 2011 to 2015 that had been published by RAFTS and I plotted this data to see if the same two-year cycle was apparent across all of the west coast sampling sites. The answer is no it wasn’t. However, I was aware that the sampling had been undertaken for a much longer time period than the data I used. I therefore submitted a FOI request to Marine Scotland Science to access what data was available. This I did on 25th January. I heard back from the Scottish Government this week to be informed that the data from 1997 to 2019 was in fact in the public domain. When I opened the file, I noticed that it was only dated 4th February 2022!

The spreadsheet contains data for 64,884 sea trout caught from along Scotland’s west coast over twenty-two years. This is a huge number of sea trout and is probably the most accurate reflection of the status of sea lice infestation in Scotland that has been made available.

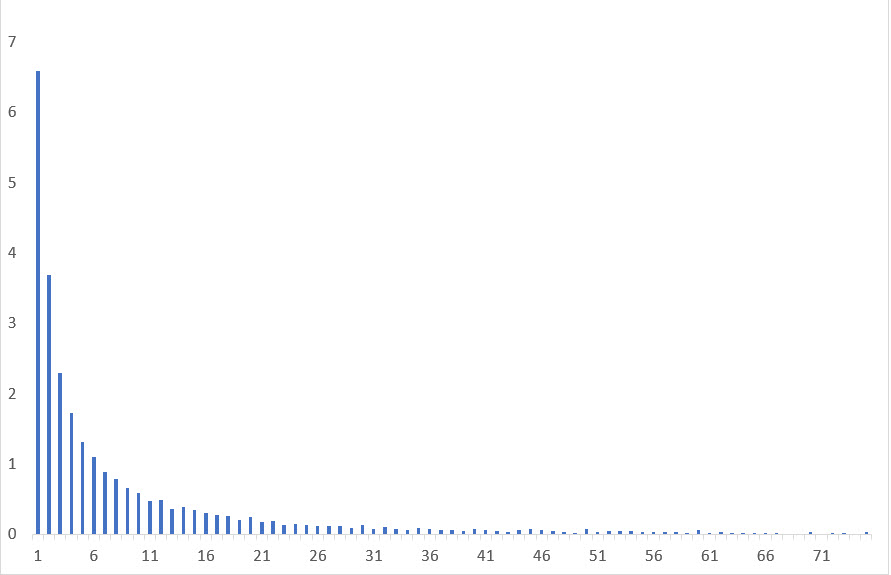

The headline news from this database is that 46,942 of these fish were lice free. This equates to 72% of the sample. A further 15.6% carried between one and five lice. The number of lice per fish up to 75 is plotted on the following graph as a percentage of the total. The number of lice free fish is so great it distorts the graph, so I have used percentage infestation instead. Even that is not ideal, thus the second graph omits all the lice free fish so the higher infestations can be seen. The graph also does not include the 1.1% of the sample with lice levels from 76 to 500 in number.

(The y axis is percentage of fish with lice infestation and x axis is the number of lice per fish)

Marine Scotland Science summary of science includes reference to laboratory experiments which claim to show that more than 13 lice were potentially lethal to sea trout. This equates to just 8% of this sample. Such mortality would hardly cause the massive decline in stocks for which salmon farms are blamed.

As can be seen, the graph is the typical aggregated distribution that has been identified from other salmon and sea trout samples from Norway. This distribution is exactly what would be expected to be seen for a parasite such as sea lice.

Just to be clear, 72% of the sample carried no lice.

What this means is that here is another piece of evidence that salmon farming is not having the deleterious effect on wild sea trout populations as repeatedly claimed. The wild fish sector will simply ignore this evidence, like they ignore everything else, and the critics will claim it to be fake. This is because as everyone knows salmon farms, in one way or another, have killed off all the wild salmon and sea trout from west coast rivers. Nothing will persuade them otherwise, even evidence that they themselves have collected (but failed to analyse).

There is one issue arising from this observation that I should address. Observations from long ago implanted the idea that sea trout infested with sea lice could return to freshwater to delice themselves before returning to sea to continue feeding. Of course, there is no way of knowing whether early returning sea trout are seeking relief from sea lice or just happen to be returning to freshwater because they were unable to find sufficient food to maintain the expense of a marine life.

If sea trout do return to freshwater to remove sea lice and perhaps the large number of sea trout observed in this huge sample that are free of sea lice have been through this process, then why don’t all sea trout act in the same way? Why are we still seeing sea trout carrying 500 lice (of different life stages)? My view is that the return to freshwater as a delicing measure has been overstated. This is because this extremely large sample shows the typical aggregated distribution also seen in salmon, and salmon don’t return to freshwater like sea trout.

This sea trout sample demonstrates that a new narrative is now required to explain the relationship between salmon farming and wild fish. Sadly, the wild fish sector is so entrenched in their established view that they are not even interested in hearing any other voice.

Our science: Salmon & Trout Conservation have issued a response to the Griggs report. I may discuss this in a future issue of reLAKSation but having had a brief read, one statement stood out. This is “Science so long as it’s ‘our’ science?” in which S&TC refer to Professor Griggs’ suggestion that a central body will collect and provide scientific advice. S&TC seem to suggest that this will be selective and only consider the science that supports the industry. They say that there appears to be no eNGO or wildlife/conservation involvement at all.

Perhaps, if S&TC are arguing for a more balanced view of the science then they should practice what they preach. They could start off by discussing the findings about sea trout discussed above or maybe they want to talk about my recent paper. In ten years of trying to interact with S&TC, they have been the most blinkered organisation as to the science that doesn’t support their narrative. The rest of the wild fish sector are not far behind.

SEEPED: The Ferret reported that staff at SEPA have demanded an independent inquiry into allegations of bullying and harassment following the sudden resignation of the agency’s chief executive, Terry A’Hearn. Since his departure, he has been interviewed by the environmental magazine ENDS and said that he was proud of his legacy after seven years of leading SEPA citing improvements in the environmental performance of the whisky industry and an overhaul of the regulation of salmon farms.

I get the feeling that Mr A’Hearn had much in common with the angling sector, by trying to deflect attention away from his own deficiencies and throwing the spotlight on the salmon farming industry.

As I have written previously, SEPA’s approach to salmon farming is a real enigma. Just over a year ago, SEPA’s head of ecology, who was sitting next to Mr A’Hearn, told the Scottish Parliaments REC Committee that salmon farms were not responsible for the declines of wild salmon on Scotland’s west coast. A year later, SEPA published a consultation document on a proposed sea lice framework for Scotland about which Mr A’Hearn said that ‘we know that sea lice from marine farms can be a significant hazard’ (to wild fish). Unfortunately, as Mr A’Hearn has now left SEPA, it is impossible for me to ask him how he knows this. At this point in time, neither do I know whether SEPA’s head of ecology has changed his mind, or whether there has been some intimidation as suggested by the Ferret.

What I do know is that as I write my response to the consultation, the scientific justification for this proposed framework is extremely flimsy. I suspect that like the Salmon Interactions Working Group, SEPA were expecting the responses to be based on the proposal and not the scientific claims made to explain the need for the framework. Those reading the consultation are probably expected to accept the narrative, despite the conflicting messages given to the REC Committee and those reading the consultation.

Although the consultation document is thirty- six pages long, the scientific justification for the proposals runs to just ten lines of text and covers three points.

The first is something I discussed at the launch of the consultation. This is the claim in section 2.1 that nearly 60% of salmon rivers across Scotland have salmon populations that are in poor conservation status. This is simply incorrect and misleading and based on numbers of areas classified as grade 3 conservation status. Instead, if actual salmon habitat is used as the measure, then the true figure is 26.9% of Scottish salmon habitat is in poor conservation status. The figure for the west coast Aquaculture Zone is just 5.96%. This is the very small amount of salmon habitat that is being targeted by this proposal. The wild salmon strategy, which is mentioned in the consultation, offers nothing to address and help the other 21% of habitat in poor conservation status.

Section 2,3 describes the second point. It states: “Substantial impacts on the marine survival of wild Atlantic salmon resulting from sea lice from finfish farms have been demonstrated in Ireland and Norway. This has been done by protecting individually tagged smolts against sea lice using an anti-sea lice medicine before releasing protected and unprotected tagged smolts into the sea near their respective home rivers.”

The document then provides nine citations to support this claim, however I am not sure that however wrote the document bothered to look at the papers or whether they had been cited simply because they have been cited elsewhere.

Of the nine citations mentioned above, numbers 9 and 10 are the most important. One is the more complete version of the other and separated by two years. Interestingly, Marine Science Scotland (MSS) only cite the earlier one in their summary of the science. The papers are by Jackson and colleagues from the Marine Institute in Ireland from 2011 and 2013. The work is important because it is the biggest study of all and involved 352,142 smolts. These were hatchery raised fish released into eight locations around south and west Ireland, rather than the home river referenced in the SEPA consultation. The number of fish caught after returning was 8,529 control and 9,678 treated, which equates to 1.13 treated fish returning for every control fish.

The conclusion of this work is that whilst sea lice induced mortality on outwardly migrating smolts can be significant, it is a minor and irregular component of marine mortality in the stocks studied and is unlikely to be a significant factor influencing the conservation status of salmon stocks. This is because around 95% of the fish failed to return irrespective of whether they had been treated or not. This is the high natural marine mortality which the wild sector choses to largely ignore.

Citation no 7 is the work of Skilbrei and Wennevik (2006) from Norway, the results of which were broadly in line with those of Jackson and his colleagues. This trial involved 10,500 hatchery fish. In total 178 treated fish were recaptured ad 106 controls equating to 1.67 treated for every control fish.

These are the two major works from Ireland and Norway mentioned in the consultation and neither show substantial impacts on marine survival of sea lice infested fish.

A fourth citation (no 11) is also from Ireland, but from researchers working for Inland Fisheries Ireland. The work is from 2012 and reached a different conclusion to Jackson from a return of just 472 in total from 74,324 smolts. The ratio of treated to control fish was 1:1.8. The high overall mortality of all fish was later ascribed to the fish being raised and then released in rivers with very different pH values.

However, and importantly, is that under an arrangement in Ireland, all such experimental data must be copied to the Marine Institute and the data from this work is part of the Jackson data.

There have been issues about the supply of data to the Marine Institute as in 1997, the Institute commissioned an independent investigation by Dr Ian Cowx of Hull University because there were concerns that not all the collected data was reaching the Marine Institute. Dr Cowx identified that amongst others, data of fish that were free of sea lice had been omitted from the record.

Of the remaining papers cited, no 5 does not refer to the release of treated smolts, so is not applicable here. Paper 6 (which is cited incorrectly) by Finstad et al. shows that the number of control fish exceeded treated and is not a peer reviewed study. Paper 8 by Hvidesten et al (2007) found a return rate of 1.5 treated fish to every control fish however, they state that the results should be treated with caution as they say that the figure is within the limits of overall variation in the natural system.

The final two papers (no 12 and 13) are by Martin Krkosek and his colleagues. These papers simply refer to different statistical treatment of the data from Norway and Ireland. The second paper is a criticism of Jackson’s work with claims that have been strongly refuted by the Marine Institute that the original statistics are incorrect. Dr Krkosek’s first foray into sea lice infestation determined that sea lice from a salmon farm in Canada was responsible for high mortality of pink salmon, even though the farm identified in his work was lying fallow for much of the time.

There is one major omission from this list of papers detailing tagged salmon returns. This is the three-year project undertaken by MSS using wild fish from the river Lochy in the west of Scotland and the river Conon in the east. This omission is likely to be because this Scottish work, which MSS claimed was necessary because Scottish fish could act differently to those tested in Norway and Ireland, does not support the claimed impacts of sea lice from salmon farms. Almost all the returns were recorded from the River Conon where control fish outnumbered those that had been treated.

Section 2.3 of the consultation also highlights the third point. The consultation states: “It is clear from this work and the wider body of scientific evidence that sea lice from open-net pen finfish farms in Scotland can pose a significant risk to wild salmon populations”.

This wider body of evidence is the MSS summary of science about which I have written many times and about which for the last six years at least, I have been waiting for MSS to explain how the selective science quoted in this summary demonstrates that sea lice from salmon farms pose even a minimal risk, let alone a significant one, to wild salmon.

The reality is that the science quoted in the consultation does not support the claims made and certainly does not justify the imposition of the proposed framework. In their consultation launch press release, SEPA state that protecting wild salmon is a national priority. The only conclusion is that SEPA have got their priorities all wrong because this proposed sea lice framework will do nothing to protect any wild salmon at all.