Not what you think!: National Geographic magazine has continued its crusade against salmon farming with another article titled – ‘When you might not be getting the fish you thought you’d paid for’. The premise of the article is that US consumers are being defrauded by being severed cheaper inferior farmed salmon when they expected to receive superior wild Pacific salmon. However, the fraud doesn’t stop at restaurants as such deception occurs at the fish counter too.

The article refers to an investigation conducted by Oceana back in 2015 in which they supposedly found 70% of 82 samples were actually farmed raised salmon rather than the advertised wild caught Pacific salmon. I say supposedly because as I wrote at the time, Ocean did not provide any examples of such deception. As I argued at the time, if they found examples of fraud, why not highlight the perpetrators as nothing would change if those engaged in any deception simply got away with it. Of course, Oceana never provided even one example of their alleged fraud.

Despite any examples, National Geographic state that many environmentally conscious seafood lovers avoid the pitfalls of farmed salmon (kindly supplied by UK campaigner Don Staniford) by buying wild caught species such as sockeye. However, these fish are significantly more expansive – often twice the cost – tempting unscrupulous seafood sellers to substitute cheaper farmed fillets for a bigger pay day. They say that a 2018 investigation in New York found 30% of sockeye samples were farmed raised Atlantic salmon.

The article says that consumers are not the only losers as seafood fraud expert Robert Hanner from the university of Guelph who said that one of the things that p**ses me off about fraud is sellers are stealing the market share from legit producers.

Hanner is now testing a new technique using stable isotope analysis that can trace the fish to the body of water from which it was caught. Hanner and his team invited National Geographic to carry out a first test of this new technique using random samples of sockeye bought from the marketplace. They bought 21 samples of mostly sockeye salmon from more than a dozen grocery stores including some that were found in 2018 to have allegedly mislabelled their fish. Other samples were supplied by a sustainable seafood supplier from BC, confusingly named Organic Ocean Seafood Inc.

Not surprisingly, all the samples supplied by OOS were found to be what they were supposed to be. Of the 21 samples supplied by National Geographic, 12 were inconclusive which was blamed on spoilage during hold ups at Canadian customs. The other nine, five labelled as sockeye were sockeye. Two labelled as Chinook salon were chinook. One sample, labelled generically as ‘salmon’, were cheap chum salmon, whilst a box of salmon burgers advertised as Alaskan wild caught were made from pink salmon. Perhaps in the case of the burgers, National Geographic should have looked at the further information provided on the back of the pack. ‘Trident’ salmon burgers (which are available in the UK) clearly state that they are made from pink and/or Keta (chum) salmon.

So, this analysis has shown that all the samples were identified as labelled with not one example of deception.

In my experience, what some might describe as fraud is simply the result of poor knowledge rather than specific attempts to mislead. Equally, I suspect that people who are willing to pay more for wild caught salmon are aware of the huge difference in taste and texture of Pacific species compared to Atlantic salmon. These are not some bland white fish which might be difficult to differentiate. These are very different fish altogether and even visually easy to tell apart.

I would suggest that these tales of fraud are just another way of attacking the salmon farming industry for producing a value for money, tasty fish offering that is an ideal everyday meal choice, by those who see their market threatened.

Wild fish 2: The last issue of reLAKSation included the first part of my thoughts on Scotland’s new wild salmon strategy. The strategy certainly merits further consideration, which I will tackle here:

The wild fish sector has always argued that the most urgent action should be taken against those pressures on wild salmon that can be most easily addressed. Their primary target has always been the salmon farming industry despite its limited geographic influence and the small size of the local wild salmon stock. Pressures such as dams and predators are considered too difficult to resolve by the sector however the one main pressure that can be immediately reduced is exploitation and this hardly merits much consideration by the strategy. This is not surprising since continued exploitation is at the heart of the wild sector’s interests.

The relevant section in the strategy is headed ‘Managing exploitation through effective regulation, deterrents and enforcement’. However, the emphasis is on illegal activity rather than more stringent control of legal exploitation. This ‘fisheries’ strategy justifies the continuation of angling by suggesting that anglers are the eyes and ears reporting illegal activity and pollution incidents. This ignores the fact that most illegal activity occurs at night long after the anglers have departed. In addition, the strategy says that anglers actively work with other to improve habitats and protect the aquatic environment. Yet this strategy clearly highlights that salmon stocks are in crisis, and this crisis has occurred under the angler’s watch.

The strategy states that actions already taken relevant to exploitation includes the of sale of rod caught salmon, which was more about message than any actual protection; a ban on coastal netting, which ignored the same heritable fishing rights that have been highlighted as an essential part of rural economy in relation to rod fishing; and changes to close times to protect spring fish through mandatory catch and release, as well as the introduction of conservation limits as already discussed. Finally, the strategy refers to a high level of catch and release.

Yet, the reality is that none of these measures has halted the decline in returning salmon numbers. They are simply a matter of tinkering around the subject rather than addressing the fundamental issue of falling numbers of returning salmon and the inevitable collapse of the spawning stock.

The ideal scenario, following the example established with net fisheries, would be a total ban on rod fishing, but this would likely be considered politically unpopular. One option would be to standardise the fishing season, as currently, every river has a different opening and closing time some of which run from January to October. The differences in each river season are apparent from recent news stories concerning the opening of rivers such as the Helmsdale and the Tay to fishing on Jan 11th and Jan 15th respectively. The river Stinchar doesn’t open until February 25th whilst the Cree only opens on the March 1st.

Given the precarious position of spring salmon, it would make sense to start the fishing season towards the end of April through until the end of September. This would effectively reduce the exploitation of threatened salmon by limiting the time that fishing pressure is exerted. Currently, the River Tay season runs from 15th January to 15th October, leaving little time for uninterrupted breeding and recovery.

Given that a strategy is now required to protect salmon following demands from the wild fish lobby for salmon to be made a national priority, more stringent measures may be needed. Norway and Ireland have adopted measures to close rivers to fishing completely. The Irish Government recently announced that 66 rivers in Ireland will be closed to fishing during 2022. In addition, 36 will be catch and release only whilst 45 will be fully open. These three categories would equate to the three river gradings in Scotland meaning that Grade 3 rivers should be completely closed to fishing, following the Irish example.

The strategy document highlights that salmon mortality can occur thorough catch and release fishing and this is exacerbated by high temperatures. Whilst MSS is promoting tree planting to avoid some of the excessive water temperatures now experienced in Scotland, there appears to be no consideration of river closures during periods of high temperature.

MSS had commissioned a study of catch and release related mortality by a PhD student. The three-year study finished some time ago, yet no results have been published and no mention of the study is made in this strategy. Estimates elsewhere suggest mortality of around 14% in other countries but the range can be large. Mortality can be further exacerbated by the handling of the fish after catching. Despite published recommendations on fish handling, many anglers appear to ignore the advice as illustrated by the many pictures posted on social media, often repeated by the Salmon Fishery Boards, who should know better. However, whilst pictures of captured fish may appear to be a record of the celebration of an angler’s catch, they also represent a sales pitch by the proprietors that says: ‘see the fish caught from our fishery’.

As there is a clear risk of mortality with catch and release, it should be mandatory that all anglers fishing for salmon should attend a fish handling course. This could be integrated into a salmon fishing licence, which would also help pay towards conservation efforts. Anglers have resisted a licence for years, but licences help police the fisheries stocks that still exist in Scottish rivers.

The strategy trumpets the move towards voluntary catch and release as a conservation measure, but the reality is that the evidence does not support that catch and release is a successful conservation measure. The River Dee has been only catch and release for twenty years and has not shown any signs of recovery during this time.

The strategy also discusses international cooperation including with the North Atlantic Conservation Organisation (NASCO) who devise regulatory measures in distant water fisheries such as at West Greenland and Faroe Islands. However, both the strategy and NASCO appear to ignore widespread exploitation closer to home.

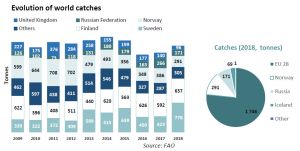

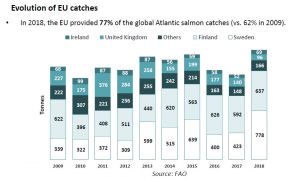

The European Commission’s agency EUFOMA (European Market Observatory for Fisheries & Aquaculture) monitors volumes, values and prices of the fisheries catch including wild Atlantic salmon. In common with data from most large agencies, there is a time lag, so their latest dataset only goes up to 2018 but it makes surprising reading. For the ten years up to 2018, an average 24,000 tonnes of Atlantic salmon have been caught and killed. If the average weight of the fish was 4.5kg, then over these ten years, nearly 5.5 million wild salmon have been exploited. Yet, whilst, the current exploitation is the lowest seen, neither NASCO nor ICES appear to suggest that this exploitation be curtailed in order to protect the species.

The most glaring omission from the strategy is consideration of stocking. This has already been dismissed by MSS are ineffective, but this might reflect the actual methods adopted. The River Carron Conservation Project has been an overwhelming success but is ignored by MSS because they claim that the river would have recovered naturally after a major spate event. The fact, that wild stocks are in significant decline across Scotland seems to have escaped their consideration. Equally, MSS claim that salmon farming has an impact on wild salmon and the River Carron is next to a major aquaculture hub, their claim that the river will recover naturally seems rather hollow. The fact that the river has recovered despite the presence of local salmon farms, would rather undermine such claims. In addition, the wild fish sector argues against stocking because of claims that the fish have been domesticated even though there is no evidence to support their view. The concept of stocking is also associated with farming and thus considered undesirable because fish raised in hatcheries are considered weak and inferior as they are not truly wild. Clearly, if stocks are low and the existing breeding stock is not providing sufficient fish to maintain a population, then the stock should be boosted by stocking. If more fish can migrate away from rivers, then the greater chance that more will return.

Interestingly, at the beginning of the month Fisheries Management Scotland posted a link to a review of stocking written by Kyle A Young, who seems to be the main driver of the argument against stocking. He sums up his view. The scientific evidence is clear: stocking is punitive not mitigative. However, it’s quite likely that Kyle Young hasn’t seen the River Carron catch returns.

The strategy highlights the value of salmon fishing to Scotland but if the number of returning fish continues to decline, then there will be no fisheries left. The strategy appears to have no real solutions as to how to improve the situation except to allow the status quo to continue as far as rod catch exploitation is concerned. I certainly didn’t expect any different.