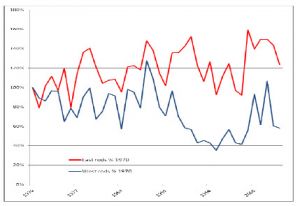

Exonerated: In 2011, the then Rivers & Fisheries Trusts of Scotland (RAFTS) published the following graph:

This features the rod catch data for salmon from east coast rivers (red) and west coast rivers (blue) in terms of percentage change. They said that the graph shows that in areas without salmon farms, catches will increase because the salmon are not exposed to the lethal effects of sea lice.

Thus, if the grilse catches, as shown in the graph below, have also increased, then they equally cannot have been exposed to the lethal effects of any sea lice.

The difference is that these catches are of fish from rivers within the west coast salmon farming area known as the Aquaculture Zone (AZ) and thus are exposed to the lethal effects of sea lice, yet these catches have increased, not declined, as the wild fish sector’s narrative claims.

What is different is that the catches shown in the second graph are of just grilse or fish that have spent one winter at sea and reported as caught by river proprietors to the Scottish Government.

The graph prepared by RAFTS is of catches of all salmon; both 1SW grilse and MSW salmon. The lower part of the graph is of total west coast catches, and these are supposed to show west coast catches are in decline and this decline is as a result of the presence of salmon farming. Yet, clearly, the grilse component of the catch is not in decline and thus it would appear that the claimed negative impact of salmon farms and their sea lice has not occurred. This observation covers almost the whole period of salmon farm development up to 2010.

The finding that grilse catches have bucked the trend comes from a new peer-reviewed paper which I have authored and appears in the journal ‘Aquaculture & Fisheries Studies.

I was prompted to look at the different components of wild salmon stocks after I came across a blog written by Stuart Brabbs, the Trust Manager at the Ayrshire Rivers Trust. The blog, dated 2nd December 2017, concerned a YouTube video posted by the River Tweed Foundation. This takes the form of an updated version of a talk given by Dr Ronald Campbell a year previously. The video uses historic netting catch data to show changes that have occurred to salmon stock over several centuries and postulates that similar changes in more recent times may be part of a very long-term periodic cycle.

Mr Brabbs says that whilst the video relates to Tweed salmon and grilse, similar trends have been seen in the Tay, Spey and Dee and he suggests that if such changes have happened on the east coast, then it is highly likely that they will have also occurred in the west too. However, he says that the rivers in Ayrshire do not have the same historic netting data as found in the east to allow such comparisons to be made. Despite the lack of such data, Mr Brabbs concludes that there are wide fluctuations between grilse and salmon with cycles extending to over 50 years and this should be considered when making assessments of the salmon stock.

Yet, whilst there is a scarcity of netting catch data from Scotland’s west coast, there is extensive rod catch data from rivers across all of Scotland, including the west, stretching back nearly seventy years. It occurred to me that if changing trends could be identified from netting data, then why would similar trends not also be apparent from the rod catch data too. Every year, Marine Scotland Science (MSS) publish a single graph showing the rod catch trend for all of Scotland. This is compiled from data submitted by nearly two thousand river proprietors and includes a breakdown of the catch into grilse and salmon, both in terms of weight and numbers.

As a regular user of catch data, I am often told that it is unreliable, especially in relation to deciding whether a fish is a grilse or a salmon as it is possible to have small salmon and large grilse. I accept that there is likely to be a margin of error but as the time series has run for almost seventy years, I believe that this error is likely to be relatively consistent throughout. I recently heard that Fisheries Management Scotland (FMS) and MSS are working towards a better method of categorising these fish. I can only wonder why it has taken them so long.

Since I originally accessed the rod catch data, I have produced trend graphs for each of the 109 fishery districts in respect to salmon, grilse, salmon & grilse, and sea trout and am aware that there can be significant variation in trends between districts. However, I never considered amalgamating all the grilse and all the salmon catches together to produce trend graphs for Scotland as a whole. After reading Mr Brabbs’ comments, it was a no-brainer. As part of this exercise, I thought it would be interesting to see what changes could be identified from catches of salmon and grilse from rivers within the AZ especially as so much of my work has focused on what happens to wild salmon in this area. It was therefore natural that I should also look at whether changes have occurred in this area too.

From the 1950s onwards, until 2010, the MSS salmon trend graph shows that catches increased throughout the period. Although MSS have never produced a comparable graph for the AZ, they published a version in a report about using catch data to measure the impacts of salmon farming. The overall trend they show is one of decreasing catches. These are the benchmarks against which I assessed the two stock components.

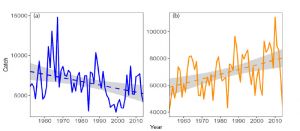

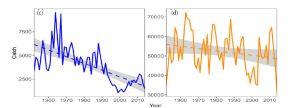

These are these graphs for the AZ in blue and the whole of Scotland in yellow for catches of all salmon.

I then looked at catches of larger MSW salmon and the resulting trend graphs are as follows:

Whilst it was of no surprise that the catches of MSW salmon from the Aquaculture Zone were in decline, catches of MSW for all of Scotland were too. This was contrary to the acknowledged upward trend detailed by MSS.

Finally, I analysed that catches for one sea winter (1SW) grilse and found that whilst grilse catches for the whole of Scotland increased, reflecting the acknowledged upward trend for Scotland, catches of grilse from rivers in the AZ also increased. Again, this was contrary to the established narrative for salmon from around the salmon farming area.

What I saw was a change in the two stock components for catches in both the AZ and across Scotland as a whole. The changes observed along the west coast were the same as was happening across all of Scotland. What this analysis showed was that far from being significantly different, the catch trends for both the AZ and the whole of Scotland were following exactly the same pattern as previously shown by the netting data from the Tweed and other East coast rivers.

This is the findings of my new paper. The data I used was publicly available from MSS and posted on the Scottish Government website. Anyone could have done exactly what I did, but the reality is that no-one had bothered because they were all far too busy attacking the salmon farming industry to take the time to investigate what was actually happening to wild salmon populations in Scotland.

The paper however raises an interesting question. As RAFTS and numerous anglers and others have regularly pointed out, the increased catch of salmon and grilse shows that they are not dying. This is because, as they say, there are no salmon farms in the east, emitting lethal concentrations of sea lice that will kill these fish as happens in the west.

However, as the catch trends show, catches of grilse in the AZ have also increased and therefore by the same assumption, they cannot be dying from lethal sea lice infestations. The reality is that the changes on the west coast mirror those elsewhere in Scotland from which the only conclusion is that sea lice from salmon farms are not having a negative impact on west coast wild salmon.

The reason why this was never obvious was that MSW salmon outnumbered the grilse, so the natural decline of larger salmon catches masked the increases of fewer grilse numbers.

Of course, I am more than willing to discuss these findings with the wild fish lobby, but I suspect that they will either try to ignore this work or rubbish it. However, the implications of the paper are massive given that the wild fish lobby are spending millions trying to track smolts in an effort to demonstrate they pass salmon farms and thus they can lobby for their closure. At the same time, SEPA are consulting on a new framework to protect wild fish from sea lice from salmon farms. Perhaps, instead of wasting time and money on these ventures, the wild fish sector should start to investigate why salmon stocks across Scotland are now so threatened. Clearly, as this work shows, there is still a lot to learn about wild salmon.

The response: More swiftly than I expected, the views of anti-salmon farming, Andrew Graham Stewart of Salmon & Trout Conservation Scotland (STCS) were sought for articles in Countryfile Magazine and the West Highland Free Press. His position can be summed up by one line in the WHFP – “Dr Jaffa is essentially a spokesman and an apologist for the salmon farming industry.” Although he makes several comments, he fails to discuss the actual findings of this peer-reviewed paper or their implications.

In addition to the wider analyses as discussed above, the paper also looks at four diverse rivers in the west to show that there is variation. Mr Graham Stewart told Countryfile that my latest output focuses on just four west Highland rivers, which are far from representative. He added that the great majority of west coast rivers have lost almost all of their wild salmon since the exponential growth of salmon farming occurred from the 1990s. Mr Graham Stewart has consistently refused to explain how the most contentious salmon farm in Scotland in Loch Ewe was located just a handful of kilometres from the River Ewe, a river that has Grade One conservation status and a river that Mr Graham Stewart has fished himself in the not-too-distant past, despite the presence of the salmon farm.

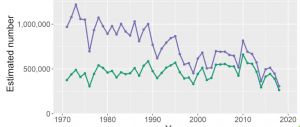

However, it doesn’t take much to see that the fate of salmon in west coast rivers was determined long before salmon farming became firmly established and certainly long before the 1990s as highlighted by Mr Graham Stewart.

The above graph is from the Scottish Government’s Marine Assessment 2020. It shows that the number of salmon returning to Scottish rivers has been in decline since at least 1970. As fewer fish return, the spawning stock of the smaller rivers shrinks at a much faster pace than the larger rivers as found on the east coast. Added to this continuous fishing pressure up to the 1990s, with almost all fish caught being killed means that the inevitable disaster actually occured. The problem is that no-one really considered the implications of what this meant, especially those who blamed the early changes on salmon farming. As we know Mr Graham Stewart isn’t interested in anything other than blaming salmon farming for the declines, which is the main reason why his organisation were thrown out of the Missing Salmon Alliance.

However, Mr Graham Stewart’s most surprising comment is that as well as trying to undermine my reputation, he also attacks his fellow anglers. He says that most anglers are unable to differentiate between large grilse and small salmon and accordingly official declared catches for grilse and salmon are based on nominal often estimated weights which can vary from year to year and from river to river. Thus, he is suggesting that his fellow anglers are incapable of determining what the fish they catch is or what it weighs. Therefore, he implies that the data that has been supplied to the Scottish Government for nearly seventy years is completely invalid. Yet, at the same time, Mr Graham Stewart, who has represented the STCS and its former incarnation, the Salmon & Trout Association has seemed unbothered about this, until I have presented my findings.

In addition, Mr Graham Stewart says that the only reliable method to determine whether a fish is a grilse or a salmon, is to examine a scale sample with a microscope. However, this brings in to question the netting data used by Dr Campbell dating back to 1740. I’m sure that all the netsmen around Scotland weren’t carrying a microscope to verify whether the fish they caught were grilse or salmon, yet they recorded the catch as such. Dr Campbell has been promoting his views on grilse and salmon cycles since 2015 yet I haven’t heard any criticism of his work. Dr Summers authored a paper on the same subject back in 1995 and yet again no criticism has been forthcoming. It is only when the results are used to vindicate salmon farming, that Mr Graham Stewart has expressed his concerns.

Finally, Mr Graham Stewart argues that numerous peer-reviewed studies, written and put together by experts in the field, and that have real credibility, show that wild stocks are severely impacted by salmon farming particularly relating to the impact of sea lice. Ignoring the fact that Mr Graham Stewart considers scientists who agree with him as experts, but others like myself, who hold a different view to him, as apologists, should Mr Graham Stewart examine these studies, he would find that almost all are based on mathematical models and what is increasingly apparent is that these models are being questioned by the wider community, simply because they bear little resemblance to what actually happens in the sea. In my experience, the mathematical modelling community have been somewhat reluctant, like Mr Graham Stewart, to enter into any open discussion about these issues.

If Mr Graham Stewart feels so strongly about the impacts of salmon farming, I am sure that a debate can be organised during the forthcoming Aquaculture UK event in Aviemore in May during which he would be welcome to offer his views. I certainly would be more than happy to share the platform with him.