Three very diverse issues are covered in this mid-festive period issue of reLAKSation. The first lists the best offers on salmon in the UK this Christmas, whilst the second is the announcement this week by the Scottish Government that they are to provide further funding of the west coast tracking project. The third concerns SEPA’s sea lice consultation.

The best deals on salmon in the UK this Christmas:

Aldi

Chilled

Whole salmon £4.95/kg

Salmon side £10.99/kg

Smoked

Smoked salmon £14.96/kg

Asda

Chilled

Whole salmon £5.90/kg

Smoked

Smoked salmon £19.57/kg

Booths

Fish counter

Salmon fillet £17.50/kg

Budgens

Smoked

Smoked salmon £16.67/kg

Lidl

Chilled

Whole salmon £6.95/kg

Salmon side £11.99/kg

Smoked salmon £19.95/kg

Marks & Spencer

Chilled

Salmon side £12.66/kg

Smoked

Smoked salmon £29.86/kg

Morrisons

Fish counter

Whole salmon £4.99/kg

Smoked

Smoked salmon £15.00/kg

Sainsburys

Chilled

Salmon side £13.00/kg

Smoked

Smoked salmon £14.96/kg

Tesco

Fish counter/ Chilled

Whole salmon £6.00/kg

Salmon side £10.00/kg

Smoked

Smoked salmon £16.65/kg

Waitrose

Smoked

Smoked salmon £26.66/kg

West coast tracking: The Times reports that satellite tracking devices are to be fitted to salmon to help them survive any dangers they face on their long migrations. However, it seems that the Times newspaper didn’t really understand the press release issued by the Scottish Government on the 28th December 2021.

The press release actually announced an additional £400,000 of funding towards the West Coast Tracking project managed by the Atlantic Salmon Trust, with partners, Fisheries Management Scotland and Marine Scotland Science. This will be the second year of the project.

Even though the tracking was of smolts, which migrated out of west coast rivers earlier this year, no results have been forthcoming. Surely, if the Scottish Government have decided to provide additional funding, then they must have seen some form of results. It is unclear why they have not been made public.

The press release includes a comment from Salmon Scotland which states that they look forward to an update from the project managers on what has been learnt from the first year of tracking. Salmon Scotland provide a significant tranche of funding to this project but clearly are not considered partners even though the main aim of the project is to help inform future aquaculture planning and regulation.

This is yet just another example that salmon farming is being singled out as a major cause of wild fish declines, even though the so-called moderates in the wild fish sector acknowledge that there might be other pressures causing the decline. Even if salmon farming significantly impacted on wild fish, which I firmly believe it doesn’t – no-one has provided a shred of evidence to support the link between wild fish declines and salmon farming except some weak correlation and as the Scottish Government acknowledge, correlation does not equal causation, the reality is that it would impact on around 5% of the Scottish stock.

The Times highlights that the problems affect far beyond the west coast with a catch of 37,196 fish in 2018 down from 100,000 in 2008. The Tay has seen catches fall from 12,000 fish in the 1980s to 4,000 in 2018 whilst Dee anglers have caught around 3,000 fish down from 9,000 in 2010.

The Scottish Government has produced a list of 12 high-level pressures affecting wild salmon yet there seems very little discussion of anything other than salmon farming. With the Scottish Government providing a further £400,000 for research relating to salmon farming, I have wondered how much research has been directed towards any of the other pressures. I have submitted a number of requests to Marine Scotland for such information, but it seems that they don’t record this detail.

The limited information so far received would suggest that aquaculture research from both commercial contracts and from Scottish Government funding now totals £4.4 million, yet by comparison, £400,000 has been spent on the impacts of netting and a further £625,000 on investigation of fish-eating bird predation. There has been extensive work on river temperatures, but this was not included in the response to my request.

It does seem that salmon farming receives a disproportionate amount of attention than is warranted but that is not surprising since the angling sector have a long-time record of diverting attention away from their own impacts, which hardly even get a mention.

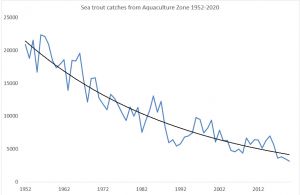

SEPA sea trout: Regular reader of reLAKSation will remember that I have repeatedly posted a graph of sea trout catches from rivers within the Aquaculture Zone (AZ) which shows declines from 1952 onwards. I have posed the question whether it is possible that whatever caused the declines during the thirty years prior to the advent of salmon farming continued to cause the declines after salmon farming was established. I have asked for any explanation of what the graphs shows and yet despite any claims that salmon farming is responsible for the demise of sea trout stocks, I have never received a single response to my request, whether from confirmed angler, vocal critic or qualified fisheries’ scientists. Given the strength of feeling about the alleged impacts of salmon farming, it is surprising that not one single person is willing to correct my own impression of what has happened to sea trout.

I have been perusing the SEPA sea lice consultation document during the holiday period and was immediately struck by the content of section 9.2

In comparison with salmon, there is very limited information on the status of sea trout populations in Scotland. Available sea trout catch statistics indicate a long-term decline on the West Coast, starting in the 1950s (pre-dating the development of finfish aquaculture) and continuing until around the 1990s. Since then, catches appear to have stabilised or even increased.

SEPA have stated elsewhere that they have been working with Marine Scotland Science and thus this statement must have been included with their knowledge.

This statement clearly indicates that sea trout catches were in decline long before the arrival of salmon farming and that in line with my observation, the rate of decline has slowed during the period when salmon underwent rapid expansion.

I have redrawn the graph with the most recent data. I would ask my question again, as to how this graph links the salmon farming industry to sea trout declines? It is difficult to see any correlation let alone prove causation.

I can only hope that 2022 will be the year when the link between salmon farming and wild fish is shown to be what it is, nothing but in the angling sector’s imagination