Note: Mr Corin Smith has been in contact and would like me to make it clear that he has never been found by a court of law or otherwise to be guilty of trespassing.

Crisis: This week, the Atlantic Salmon Trust (AST) held an online event titled ‘Restoring Wild Salmon Populations’. In the final presentation of the evening, head of research at the AST, Professor Ken Whelan revealed a slide stating that ‘wild Atlantic salmon are in crisis’. Professor Whelan emphasized that thirty to forty years ago 25 salmon from every 100 smolts returned to the rivers to breed, whereas the number now could be as low as 5 for grilse or 2 for larger salmon. He stressed that those numbers, by any standards, are catastrophic.

Although the suggestion is that this is a recent revelation, the writing has been on the wall for a considerable time now.

My interest in wild salmon through its interactions with salmon farming began in October 2010 after being asked to debate the issues with the then head of NASCO, Malcolm Windsor at a meeting at Fishmongers Hall in London. Around the same time, after the then Salmon & Trout Association petitioned Scottish Parliament for more stringent controls on salmon farming, the SSPO issued a one-page fact sheet about wild salmon. At the time, my interest had not sufficiently developed to really appreciate those facts then, but they are certainly worth considering now.

For example, in his presentation, Professor Whelan repeated that the number of returning salmon has fallen from 25% during the 1980s to less than 5% now. Yet, the SSPO fact sheet highlighted that during the period 1964-68 approximately 40% of the fish returned to the River North Esk near Montrose on the East coast but by 2000-02, the numbers returning to the same river had dropped to 9%.

This massive decline up to 2002 was surely reason to start ringing the alarm bells.

What makes it even more surprising is that we know this data because the Fisheries Research Services (Now Marine Scotland Science) have been studying this river for many years https://www.gov.scot/publications/salmon-and-recreational-fisheries-monitoring-north-esk-research-river/

This link includes the statement that ‘meticulous work over many years on the North Esk provides important insights into population trends and can help scientists identify those phases of the life cycle where there are problems.’ A fall of 32% in the number of returning fish by 2002 would seem to be a major problem, yet this problem seems to have created little urgency. This is because although marine mortality was, and still is, unusually high, reduced net fisheries allowed more fish to return to the river. Therefore, despite a massive decline in the number of returning fish, there were still plenty of fish for anglers to catch.

Consequently, the River North Esk has maintained its Grade one conservation status since the measure was introduced in 2016. Clearly, in the eyes of scientists from Marine Scotland, everything is hunky dory and the decline of returning wild fish has not been something affecting the conservation status of the river.

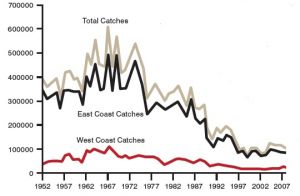

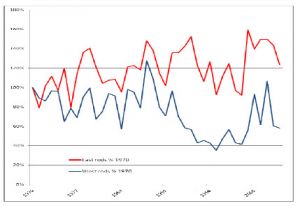

Back in 2011, the SSPO also highlighted that the annual number of salmon caught across Scotland by all methods peaked in 1967 at just over 600,000 fish. Although, as I have regularly pointed out, catches from the west coast are only a tiny component of the total catch, both east and west catches peaked at the same time. After this high point, numbers caught by all methods declined across Scotland so that by 2000, the number had fallen from 600,000 to around 100-120,000 fish. It is likely to be even lower now. These trends can be seen in the following graph taken from the SSPO fact sheet.

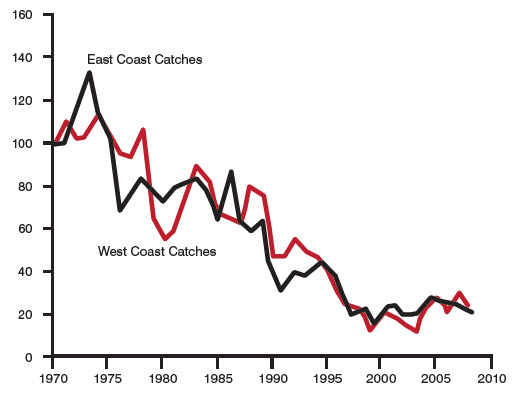

Because of the difference in the size of the catch from both the east and west coast, the SSPO also calculated the percentage change in east and west coast catches using 1970 as a reference point. The data is for all methods of capture and shows remarkably similar patterns of decline from 1970 onwards. The SSPO pointed out that salmon farming did not really start until the 1980s.

This graph also should have started the alarm bells ringing amongst anyone concerned about wild fish, but the bells did not ring. In fact, rather than show any concern, the wild sector, in the form of RAFTS, the Rivers and Fisheries Trusts of Scotland, undertook to discredit the SSPO fact sheet. Later in 2011, they issued a short rebuttal, which was titled ‘Comparison of the decline of Scottish East and West Coast Salmon Fisheries.’

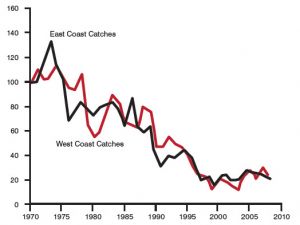

The first point they made is that the SSPO’s analysis of the west coast includes a ’substantial area where there is no aquaculture’ and that is a fair point. I use the area known as the Aquaculture Zone in my own comparisons. RAFTS have therefore helpfully redrawn the graph comparing the West Coast Aquaculture Zone with the East Coast catches as the percentage change from the 1970 reference point.

Their graph is shown below.

Their graph is hardly any different to that produced by the SSPO. Even then, why weren’t the alarm bells starting to ring?

Instead, RAFTS stated that this comparison gives a misleading picture due to the inclusion of catches by netting. They said that net catches decline in a quite different way to catches by anglers. Their explanation was that the decline in net catch had been falling for a variety of reasons including buyouts by the proprietor because the rod fishery is more valuable; ceased operation for conservation reasons or because they were uneconomic.

Some years ago, I was introduced to a netsman from a west coast net fishery, and he made it clear that the only reason the net station was closed down was because they were failing to catch any fish. This might be interpreted as being uneconomic, but it is for a very different reason. More recently, I tried to obtain data from Marine Scotland as to when the various net stations ceased operation, but seemingly such data was never recorded.

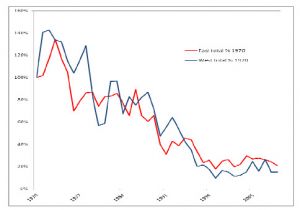

RAFTS appeared to believe that the inclusion of net catch data belied what was truly happening to wild salmon catches in Scotland. They reproduced the graph using rod catch data only.

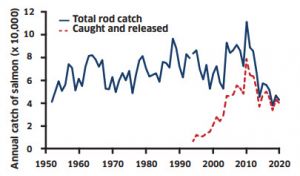

This appeared to suggest that up to 2010, rod catches on the east coast had increased whilst those on the west coast were in decline. This narrative supports their claim that catches in the Aquaculture Zone are in decline because of salmon farming. RAFTS do acknowledge that the east coast increase has been fuelled by a decline in netting thus allowing more fish to enter the rivers which were then caught by anglers. Yet, this view that catches had increased means that the underlying issues have been ignored. The reality is that there were not more fish in the Scottish waters rather that anglers were simply catching the fish that would have been otherwise caught by netting. Increased east coast rod catches have deflected attention away from the developing crisis and this has become more apparent over the last decade as east coast catches have crashed. This increase is also apparent from the annual graph of salmon catches published this week by MSS.

With no commercial netting operating in Scotland, perhaps it is time for the anglers to look at their own activities rather than persist with blaming everyone and anyone but themselves.

Professor Whelan described the current situation as a crisis. I did not hear any solutions from the AST event that would inspire any confidence in bringing about the restoration of Scottish salmon stocks. Engaging now in long-term tracking projects only defers the inevitable when urgent action is required now.

It seems to me that there are only two immediate actions that the wild fish sector can take. They can either stop angling to ensure that every fish gets the opportunity to breed. However, this is something that they will not want to do especially as catch and release has reduced exploitation. Yet, we still do not know whether catching and releasing salmon causes unseen high levels of mortality or impedes successful breeding. MSS have conducted a study but attempts to see the results have so far failed.

If anglers do not want to stop fishing, then the alternative is to restock, which they equally do not want to do. Given a lack of viable alternatives, it is not surprising that they prefer to focus all their attention on the salmon farming industry.

I realise that the wild sector has acknowledged that there are other pressures affecting wild salmon, but following the formation of the salmon interactions group, no attempt has been made to establish other working groups for other pressures. Meanwhile, the wild fish strategy group has met extremely infrequently, which I guess reflects the lack of any urgency to resolve this crisis.

Evidence: One of the most interesting parts of the AST’s evening were the comments made by Robert Mitchell, the ghillie from the Macallan Estate. He has worked on the river for the last twenty-six years and recounted that over that time he has seen enormous change with a huge decline in salmon. He also described how after the fishing season on the Spey ends, he goes fishing every year at Stanley on the River Tay, a river with a longer season then the Spey. The pool he fishes used to be full of Autumn fish which he described as absolutely jam packed with hundreds of fish whereas now, he is lucky to see even three or four fish in a day. Mr Mitchell also related how he used to see the smolt runs coming down the Spey daily whereas now he might see it once a week.

These are observations of someone who works on the river and are fundamental to the knowledge of wild salmon. The Spey and The Tay are two of Scotland’s premier salmon rivers, not some little-known backwater on the west coast. These rivers are not impacted by salmon farming yet are clearly in suffering from a lack of fish. This is why it is inconceivable to me that every scrap of research is not directed at these important rivers, which form the heart of Scotland’s wild salmon populations.

The AST event began with a film featuring actor and AST ambassador Robson Green who tells Mark Bilsby, CEO of the AST, that there are so many opinions as to why salmon are going missing. Where Mr Green lives near the River Tyne, it is said to be the seals – he says that there are thousands of them at the mouth of the river.

He is also told that it is the brown trout that are eating young salmon. If it’s not brown trout then it’s the cormorants, or the goosanders, or even the pike. Mark Bilsby replied that there is no shortage of opinions. He says that if you ask five people what the problem is with salmon, then you get ten opinions.

The AST say that there is a need, not for opinions, but for really good robust independent science to provide the evidence required prior to making any decisions as to the best way to help protect wild salmon.

Yet, when it comes to salmon farming, there is a dearth of hard scientific evidence to show that salmon farming is having a negative impact on wild salmon stocks. The evidence I have seen is largely circumstantial and yet the salmon farming industry is portrayed as one of the major causes of salmon declines although this usually comes with a grudging admittance that there are other factors too.

Perhaps, the AST may be able to provide some robust science-based evidence that salmon farming is actually responsible for the crisis in wild salmon stocks, but I doubt it.

What’s the catch: Marine Scotland Science belatedly published the salmon and sea trout catch data for 2020 last Wednesday. Not unexpectedly, due to COVID, catches are down on previous years, but anglers still managed to catch 45,366 wild salmon and grilse of which 3,018 were killed. Anglers also caught 13,313 sea trout of which 1,565 were killed.

I will discuss the data in a future issue of reLAKSation.