High Risk: One of the oldest bridges in Scotland can be found in the town of Dumfries in the south west of the country about 32 km west of the border with England. Dervorgilla Bridge is named after Lady Dervorgilla of Galloway who arranged for the first bridge to be built over the River Nith in 1270. Parts of the current bridge, including a Gothic arch, were built around 1460 but most of that bridge was subsequently washed away. It was reconstructed in the 1620s and that is the bridge that remains today. The remaining Gothic arch can be seen in the following photo.

The River Nith, which flows under the Dervorgilla Bridge, is about 112 km long if measured at low tide. It rises in the hills of east Ayrshire and runs south through Dumfries to reach the sea in the Solway Firth. It is Scotland’s seventh longest river.

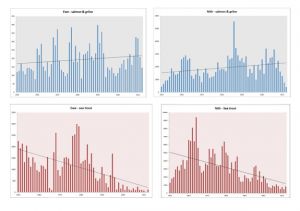

The River Nith came to my attention early on during my research into the impacts of salmon farming on wild fish stocks simply because the graphs of the salmon and sea trout catches from the river looked remarkably similar to those from the River Ewe. Salmon farming in Loch Ewe was blamed for the collapse of sea trout in nearby Loch Maree, even though catches of salmon in the same system were increasing. The River Nith also showed increased salmon catches whilst sea trout catches declined.

The following image shows salmon catches in blue and sea trout catches in red. The catches from the River Ewe are on the left and those from the River Nith are on the right.

After Andrew Graham Stewart of Salmon & Trout Conservation defamed me in Trout & Salmon magazine, I was given a couple of pages to write about my research findings. I pointed out that the River Nith emptied into the sea at least 200 kilometres from the nearest salmon farm then clearly something else, other than salmon farming, is causing the decline of sea trout even though salmon catches were rising. I posed the question asking could it be that whatever is causing the declines in the River Nith also caused the collapse of the Loch Maree sea trout fishery.

As a friend of Trout & Salmon magazine, Mr Graham Stewart was given the opportunity to reply and debunk my findings. Writing about the River Nith, Mr Graham Stewart responded saying that the Nith is a ‘complete red herring’. He continued: ‘the Nith, in common with the rest of non-salmon—farming areas of Scotland, has not lost all of its mature sea trout as the T&S river reports show with references such as ‘two sea trout with a combined weight of 11lb 8oz. Furthermore, the Nith hardly bears comparison to the Ewe system; the former meanders through coal-mining and agricultural land, whereas the latter runs off barren mountainous terrain.’

Whilst I am well aware that Mr Graham Stewart blames salmon farming for the decline of sea trout in the Ewe system, he did not offer any explanation as to why sea trout catches from the River Nith have also declined. He certainly does not imply that the declines in the Nith are in anyway connected to salmon farming. The local fishery board has written a 2020 update about the board, their activities and the river. With regard to sea trout, they say that ‘there is no firm evidence as to what is having an impact on their numbers’ even though as the graph shows sea trout have been in decline for years. Like Mr Graham Stewart, they make no mention of salmon farming in relation to what is happening to wild fish catches from the River Nith.

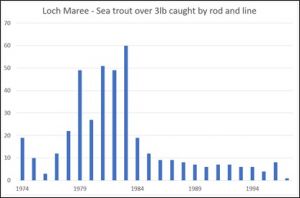

Mr Graham Stewart is however correct in saying that larger sea trout are still being caught from the River Nith, although as Loch Maree is no longer overfished, it is possible that sea trout are now able to grow to a larger size. It can be seen from the following graph that just prior to the collapse, much larger numbers of larger sea trout were taken from the loch.

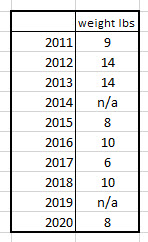

The following graph is the size of the largest sea trout caught from the River Nith over the last decade. According to Mr Graham Stewart, these fish grow to such sizes because they are free from the sea lice that have destroyed sea trout stocks in North West Highland rivers. Alternatively, the sea trout are not so intensively fished from the River Nith as they were from Loch Maree.

In a previous reLAKSation I discussed the Fisheries Management Scotland annual conference and mentioned that in her presentation, their Interactions Manager Polly Burns, had referred to a spatial planning model for consenting. She explained this by saying: ‘This is a tool that will inform planners on areas of high risk in relation to the impacts on wild fish from aquaculture and areas where development can continue in a sustainable fashion. This is really important because at the moment we simply do not know which the areas of high risk may be and where they are not happening. We really want to see that pushed through, so it is disappointing that as yet, we don’t have a response from the Scottish Government.’

However, what Polly Burns said is confusing, since as I have previously pointed out, SEPA, who are also part of the Technical Working Group tasked with the production of this tool, have clearly stated to the Scottish Parliament’s REC Committee that salmon farming is not responsible for the decline of wild fish which begs the question as to why there needs to be this tool at all. Clearly, if salmon farming is not responsible for the declines of wild fish, then there cannot be areas of high risk because all areas are of no risk.

I have heard various rumours about this tool since it was first conceived. There was talk that this would be the equivalent of the Norwegian Traffic Light system but rather than dividing the west coast into production areas, red, yellow, and green classifications would be ascribed to different areas of sea and thus a planning application for a new farm or an extension to an existing farm would be viewed very differently if it were sited in a red area to that of a farm proposed for a green area.

Disregarding the inconsistency in producing a tool to control something that has no or very minimal impact, and given the obvious flaws in the Norwegian Traffic Light system, there should be real concerns about a form of regulation based on the type of modelling used extensively in sea lice research.

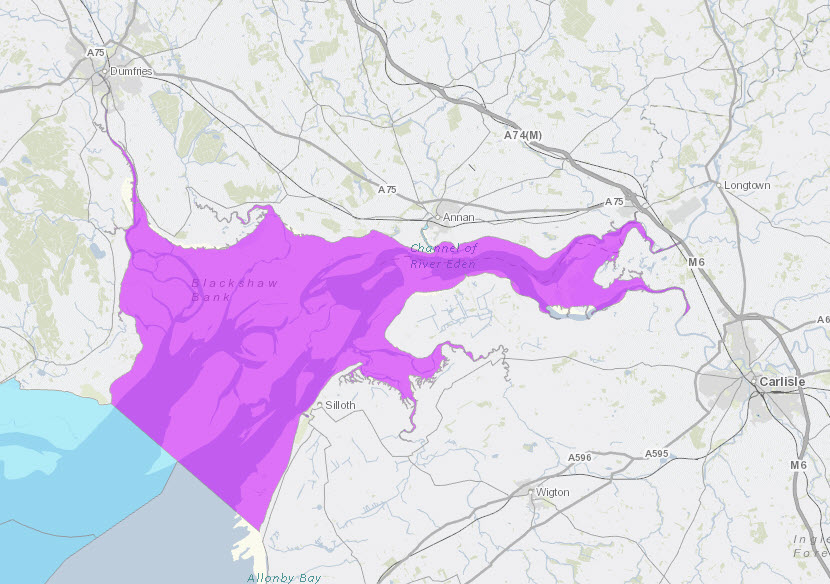

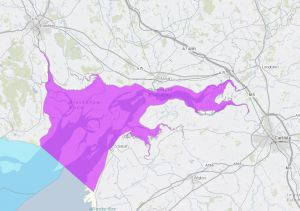

Following past comments, I have been sent a link to a map on the ArcGIS geographic mapping information system. Although it is freely available on a website, it is not yet in the public domain, so I am not at this point sharing the link. What the link is to is a map showing all the areas of high, medium, and low risk determined by the expert modelers in the Technical Working Group. What I am going to share is one of the identified high-risk areas as shown in the following image.

To anyone who doesn’t recognise the area highlighted, the following map shows the location and also for reference the site of the nearest salmon farm (marked by x).

To be clear, this high-risk area determined by the modelers is at the head of the Solway Firth near the border with England, covering the mouths of the rivers Nith and Annan. It is approximately 200 km from the nearest salmon farm which in direct line is blocked by most of the south western land mass of Scotland. Of all areas identified as a high risk to the threat of sea lice infestation from salmon farming, this must be one of the least likely. It is extremely puzzling that when the modelers drew up this map, that they didn’t wonder how the mouth of the River Nith could even be considered an area of risk to wild fish from salmon farming. After all, even Andrew Graham Stewart has never identified the area around the Solway Firth as being at risk from salmon farming.

The problem is that this is clearly not an aberration because other rivers along the Solway Firth are also considered high risk. These include the Urr (also known as Urr Water), the Dee (Galloway), the Bladnoch and the Cree. The Fleet, which is near to the Cree, is considered to be of medium risk.

The obvious question is as these areas are considered high-risk by modelers, even though local fishery boards and other wild fish organisations do not see them as threatened by salmon farming, then it brings into doubt the validity of the whole modelled tool.

I suspect that the model on which this tool is based has been developed using the same principles of the Norwegian Traffic Light system, which simply shows that extrapolating the modelling has enhanced its flaws making them even more apparent than ever.

Marine Scotland and SEPA have not yet publicised their spatial planning tool. It is unclear why it has been delayed but if the map is anything to go by then it requires a lot more work. However, as sea lice from salmon farms are not responsible for the decline of wild fish, then it is probably best if the tool is archived and disregarded.

Westward: I noticed on social media that the 20th annual meeting of the International Atlantic Salmon Research Board will take place in May. IASRB was established by NASCO in 2001 to promote research into the causes of marine mortality of Atlantic salmon and the opportunities to counteract this mortality. I will follow this meeting closely because even after twenty years, IASRB appear to have remained strangely quiet as to their findings as to why Atlantic salmon are dying at sea and even more quiet about ways to counteract this mortality. However, this is not why IARSB have come to my attention.

One of the documents included in the agenda is the SALSEA-Track Final Report https://salmonatsea.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/ICR2104_SALSEA-Track-Final-Report.pdf and this lists twelve projects as part of the salmon at sea tracking. It is number eight that caught my eye – the West Coast Scottish Array. This is the west coast tracking project.

Progress about the project is provided by John Armstrong (MSS), Mark Bilsby (AST). and Alan Wells (FMS) and it makes interesting reading. I make no secret of the fact that I think this project is a total waste of both time and money. This is because as the progress report states, the aim is to help inform planning decisions in relation to salmon aquaculture. However, given that Peter Pollard, Head of Ecology at SEPA, told the REC Committee that sea lice from salmon farms are not responsible for the decline of wild salmon and also given that planning decisions have been successfully approved for over forty years without knowledge of wild salmon migration routes, there are surely more important issues to investigate about wild salmon than this project.

I wasn’t aware that the project aims to confirm previously predicted migration routes based on particle tracking models together with local water currents. I am even less convinced of its merit.

However, my greatest concern is that the first stage is classed as a pilot project to determine whether the arrays pick up the tags and are capable of differentiating between salmon from different rivers. I fail to understand why huge amounts of money are being spent on a project where researchers do not even know whether they can identify the salmon they will be attempting to track. Perhaps this is something they should have established before seeking funding for the project. Given this is one of twelve tracking projects listed in this report, surely there must be some appreciation of whether these fish can be successfully tracked without the need for a pilot project.

However, I shouldn’t be surprised. I am remined of the £1 million FASMOP project which concluded that the ‘magnification’ of the genetic testing wasn’t sufficient to identify if fish were of different stocks. Perhaps, the researchers should have tested the method prior to the start of the project. I am also reminded of the west coast smolt release project where the traps failed to catch any of the returning fish.

I am led to understand that one of the issues of marine tracking is that the arrays need to receive a much more powerful signal than the ones used in rivers. This means that the tags are much larger and much more invasive especially in very small fish. I believe that there is a significant risk that the tags may kill the fish even before they reach the first array. However, I suspect that if this should happen then I have no doubt sea lice will be cited by the wild fish sector as the reason why the fish disappeared.

Cleared: Stewart Graham, head of Gael Force Group, has written an opinion piece for the Press and Journal in which he expresses concern about the future of the Highlands and Islands.

His extensive commentary leads to a consideration of planning applications and that in the opinion of some people, all forms of nature now have precedence over the needs of their fellow human beings. He likens the new trends in planning to the Highland Clearances where the welfare of those who work the land and the sea is of secondary considerations to the interests of a minority, often of people who are not even rooted in the area. Mr Graham says that the depressing familiarity of narrow interest groups’ objections to development, often by an outspoken minority, is heading towards being a crisis. He says that this must change, or rural areas will become a place where the will of the few surpass the opportunity of the many.

His comments follow the decision to refuse planning for an organic sea farm in Skye which would have created nine new jobs and was recommended for approval.

I have become interested in planning application following the decision by Fisheries Management Scotland to object to a farm in Kilbrannan Sound. They, or the local fisheries salmon boards, have probably objected to many others but in this case, FMS posted their objection on their website.

Frankly, the objection was the usual nonsense from the wild fish sector claiming that the presence of yet more salmon pens would destroy the stocks of wild fish, despite a complete lack of evidence to support their claims. At the same time, FMS are demanding a new regulatory process for salmon farms in order to protect wild stocks. This was one of the recommendations of the Salmon Interactions Working Group.

Given the pressure to change the current system, I have been considering how the difficulties of the current planning process can be resolved and my view is that over the years the planning system has become bogged down in unnecessary and unsuitable regulation. We need to go back to the drawing board.

The reality is that a salmon farm is not a permanent structure. It floats and is simply anchored to the seabed. Should the operator so wish, the whole structure can be moved, leaving no trace of its former presence. It is just a temporary structure and should be treated as such.

The salmon farming industry has existed sufficiently long that it is now possible to understand the local impacts on the seabed, but we also know that any impacts can be quickly reversed with time.

Of course, some locals object to views being compromised, but the view is of a floating platform and that is not much different to that of a marina, which by comparison is judged to be acceptable. As Mr Graham rightly points out, many of those who object, have moved into the area and have been surprised by the fact that there are local communities who actually need to work.

Meanwhile, the solution to planning is that after a simple review, temporary planning should be approved with the site being subjected to regular monitoring. The current system is just too cumbersome for what is not a permanent structure and for objections that are not based on firm evidence.

Of course, any new developments that differ from the existing salmon model should be subjected to a more stringent examination by planners but for standard salmon pens, the current planning process is no longer appropriate.