Red Light, Red List: In reLAKSation no 1012, I highlighted that the Norwegian Government had closed additional river systems to salmon fishing as well as many areas of the sea. After reading my comments, one of my Norwegian readers sent me the official Government statement on the closures. This states that the proportion of salmon that survive the thousands of kilometres of migration has more than halved in the last thirty years in part due to the impacts of farming and climate change.

Given that the Norwegian Environment Agency who advise the Norwegian Government set up the Scientific Committee for Salmon Management, (Vitenskapelig råd for Lakseforvaltning – VRL), it is no surprise that salmon faming is highlighted as the reason for the closure of these additional rivers. This is because VRL see salmon farming as the greatest threat to wild salmon stock. Climate change is, however, a totally different question.

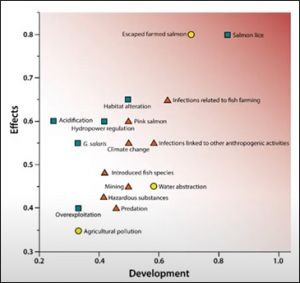

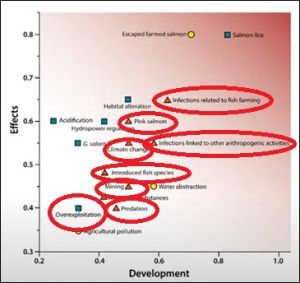

On their graph ranking 17 of the factors impacting wild salmon, climate change is placed mid-way in VRL’s ranking and it is attributed as having poor knowledge and high uncertainty unlike sea lice from salmon farming of which they say has extensive knowledge and low uncertainty. In their 2020 report, VRL say that a more accurate assessment of the risk can be made when more data becomes available. Yet, the Norwegian Environment Agency has clearly not waited for any of this new data, since climate change is cited as one of the two factors that has prompted them to impose the closure of many more salmon fisheries.

Not long after the announcement of these river and sea closures, the Norwegian Species Data Bank (Artsdatabanken) launched a new version of the Norwegian Red List of Species which covers the species that are at risk of extinction in Norway. According to Intrafish, wild salmon has been rated as ‘near threatened’ and this is because the biggest threats to wild salmon have not been stabilised. Artsdatabanken say that the two biggest threats to wild salmon in Norway are genetic introgression and sea lice.

The new rating for salmon was presented by committee member Peder Fiske from the Norwegian Institute of Nature Research. Intrafish do not mention that Dr Fiske is also a member of VRL, a group who also list genetic introgression and sea lice as the greatest threat to wild salmon in Norway.

By coincidence, VRL’s leader Dr Torbjørn Forseth was invited to speak at the Fisheries Management Scotland (FMS) annual conference on 23rd March. His presentation was titled ‘Assessing threats to Atlantic salmon in Norway’. His presentation may eventually be posted on the FMS website, but I already knew what he was going to say because he had given the same presentation to the Scottish Fisheries Coordination Centre’s meeting of fisheries’ biologists on 3rd February. However, his more recent presentation was a shorter cut down version of the one he gave in February.

Dr Forseth recounts how he has been the leader of VRL for the last twelve years and he said that the Committee has been a success especially in improving the spawning stock with nearly 90% of stocks attaining their conservation limit. Dr Forseth explained that this has meant that over-exploitation has been removed as an impact factor on salmon stocks in Norway.

During the FMS conference, I asked Dr Forseth why, given that VRL have been so successful in ensuring that so many stocks have attained their conservation target, in addition to the removal of over-exploitation, have so many additional rivers and parts of the sea suddenly been closed to fishing. His reply seemed to suggest that these new closures were just of small, inconsequential rivers! Yet, 591 rivers and large parts of the sea, seem neither small nor inconsequential in terms of overall salmon stocks.

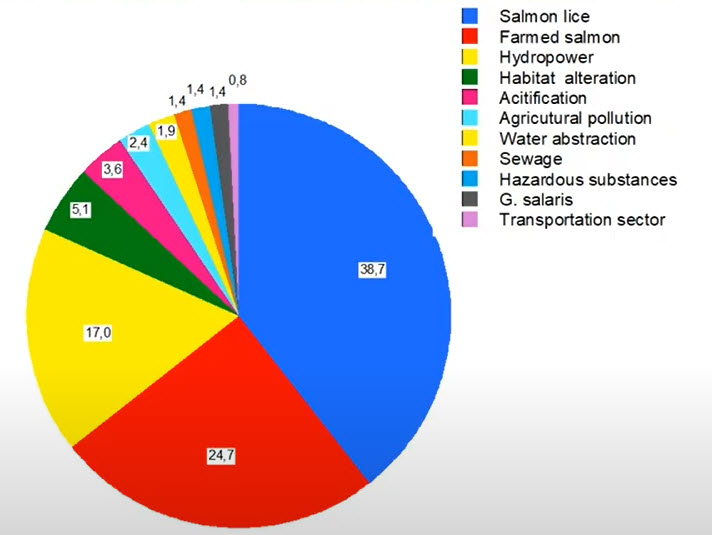

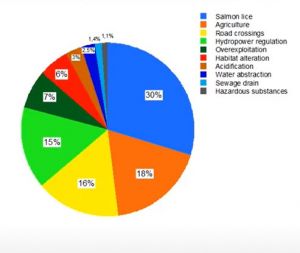

The main intention of the presentation was to discuss the various threats to wild salmon and how VRL ascertain the level of threat. Dr Forseth pointed out the threats (or pressures) are different to those listed in Scotland and also that in Norway, they prioritise them differently. VRL have calculated the impact of each threat for all 430 salmon rivers and have displayed them in a large table. Dr Forseth also presented a pie chart for all the anthropogenic factors, combined from all the rivers, which shows the size of each.

Dr Forseth highlighted that salmon lice are the strongest anthropogenic factor at 38.7% with escaped farmed salmon second at 24.7%. Together, these two threats total 63.4%. Whichever way this is considered, VRL certainly see salmon farming as the greatest threat to wild salmon in Norway. Dr Forseth continued to say that these numbers are then used to rank the threats as displayed in the graph.

Given the high numbers in the pie chart, it is not surprising that threats relating to salmon farming are placed high in the graph, well away from any other potential threat. However, the most interesting aspect to these graphs is that I have skimmed through the Norwegian versions of most of the annual status reports for wild salmon published by VRL and have never come across any version of the pie chart in any report. The last report for 2020 ran to 152 pages so space could not have been why the pie chart has not been included. Perhaps, the location on the threat graph is less provocative than the numbers of the pie chart. After all, saying that salmon farming represents 63.4% of the threat to wild salmon is very different to saying that sea lice have 0.8 effect and 0.9 development threat. Interestingly, Dr Forseth stated that “the first time they published the threat graph above, it created a lot of noise with various industries etc attacking VRL quite strongly but no-one went into the table and said that number is wrong, and today this way of communicating the threats has been accepted by all the authorities and all the industries as an important way of looking at the threats to wild salmon in Norway and currently the ‘high temperature’ has cooled considerably.”

My interpretation of Dr Forseth’s comment is that VRL have, certainly in later years, been reluctant to engage outside their clique and that anyone who objects eventually gives up trying. Whilst Dr Forseth says that VRL’s analysis of the threats has been widely accepted, such acceptance is not unanimous. It doesn’t help that despite publishing a 152-page annual report, some of their most basic data is misleading.

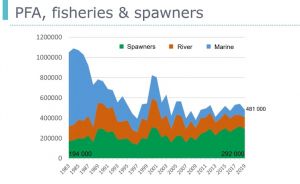

The following graph is taken from Dr Forseth’s presentation, but the same graph appears in the 2020 report but without the added numbers.

The report states that the PFA is 481,000 fish and that the total reported catch for sea and river fisheries is 136,000 fish. This would mean the spawning stock is 345,000 fish but the graph seems to imply that the figure is 292,000 leaving 53,000 fish unaccounted for.

The Norwegian version of the report does refer to 292,000 fish but states that it is the average number for the last five years. Yet, if a line is drawn across the graph for the latest spawning stock it appears to be under 300,000, well short of the 345,000 calculation. It shouldn’t be so difficult to provide the three numbers, the sea catch, river catch and spawning stocks for each year in their report rather than the restricted data that they publish.

I am interested in the exact numbers because it is possible to turn some of their claimed impacts, as appear in the pie chart, into actual numbers. The 2020 report states that with regard to sea lice:

“In 2010-2014, we estimated that 50 000 fewer salmon returned from the ocean to Norwegian rivers each year due to the impacts of salmon lice. For 2018, we estimated a reduction of 29 000 salmon due to salmon lice, and for 2019 a reduction of 39 000 salmon.”

This means that in 2019, the PFA would have been 520,000 salmon (481,000 plus 39,000) representing a loss of 8% of the existing PFA. Yet, the pie chart shows sea lice as having a 38.7% impact which is not an insignificant difference. VRL state in their report that sea lice are considered an expanding population threat which means that they are affecting populations to the extent that populations may be critically endangered or lost in nature. Yet, in 2019, the PFA is calculated to be down just 39,000 smolts. By comparison, exploitation has removed 136,000 wild salmon from the total stock – 54,000 from sea fisheries and 82,000 from rivers (numbers also not provided in the report).

Returning to the pie chart, it is interesting to note that not all the threats are included. As can be seen, this is not just one or two.

All except overexploitation are considered to be of poor knowledge and high uncertainty. It might be suggested that if Norwegian researchers didn’t spend all their time producing the hundreds of papers about sea lice and integration, and instead worked on some of these other threats then the knowledge about them might be much improved.

The Norwegian Environment Agency said that climate change was also one of the reasons why they had decided to impose sea and river closures. These closures imply that exploitation was also too high. Perhaps, if climate change and over-exploitation were included in the pie chart, the size of the threats might change. For example, if climate change amounted to 50% threat and overexploitation 25%, then the impact of sea lice would be 9.6% – not too far from the 8% calculated from the 39,000 smolt loss. Introgression would also be much lower at just 6%.

Perhaps, it is not surprising that VRL do not include the pie chart in their report.

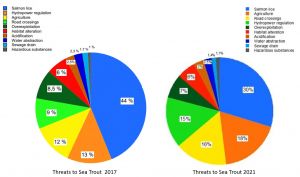

In his presentation, Dr Forseth also mentioned that he was working on threats to sea trout and showed another pie chart relating to them.

This pie chart opens up a whole new set of issues but in this commentary, I will focus on just one – sea lice.

According to this pie chart, the threat to sea trout from sea lice is 30% as compared at 38.7% for salmon. This is surprising because since I started investigating the interactions between wild fish and salmon farming in 2010, everyone I have consulted has told me that sea lice are not such a problem for salmon whereas they are for sea trout. This is because whilst salmon migration takes them past salmon farms in a couple of days, sea lice remain in coastal waters during all their time at sea and thus are continually exposed to sea lice pressure. This difference is certainly not reflected in the VRL pie chart. Perhaps, the lower figure is because other threats have an increased impact. This is something for consideration is a future reLAKSation.

Whilst I said that these pie charts are not included in VRL for salmon, I have found one in a report for sea trout from 2017.

What is surprising is that three years ago, the threat of sea trout from sea lice was 44%, 14% more than now. Whilst, VRL say that sea lice represent an expanding threat to salmon, it has clearly reduced for sea trout despite their longer exposure. Please note that in comparing the two charts above, VRL have not used the same colouration for each threat so direct comparison is fraught with difficulty. I have to ask that if they cannot address such a simple issue as the colour of a pie chart, then what hope is there for the science?

Dr Forseth’s presentation to the Fisheries Biologists can be viewed on You tube at:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H50LOQAStbQ

His FMS conference presentation is now on-line and can be viewed at:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zxKYm1nOrI8

Case against: Intrafish reported that the salmon farmers case against the Government regarding the Traffic Light decreased production was not about reviewing the research but rather concerned the legal issues. The lawyers involved in the case issued a statement that said the main issue was whether the law’s condition for reducing the aquaculture industry’s production had been met.

If this was their belief, then in my opinion the legal advice given to the farmers was wrong because this case was all about the research. However, I have some sympathy for the lawyers as they were employed by just one group of farmers, who were impacted by the implementation of the research, whilst the rest of the salmon farming industry sat on the side lines. The reality is that the salmon industry should have challenged the whole concept of the Traffic Light system before it was introduced. They should have actively been involved in the discussion rather than allow the scientist to dictate the policy.

Sissel Rogne, head of the Institute of Marine Research, has written that she is pleased that the lawyers have clarified their position because she and the researchers were left with a different impression and that it was the research that was being attacked. Dr Rogne told Intrafish that science is handled through internationally recognised academic methods which ensure thorough and critical quality assurance.

However, she only needs to read my previous commentary to see that the thorough and critical quality assurance can be significantly lacking when it comes to research that involves the salmon farming industry. There are plenty of examples.

The Norwegian Research Council have instigated a review of the Traffic Light system with a panel of overseas scientists. However, this review is already flawed because some of the scientists are clearly involved in some of the issues. However, the fact that such a review is underway suggests that there are questions being asked about the credibility of the Traffic Light system.

What is really needed is a wider consultation involving scientists from the industry and other professional organisations alongside the existing research community. I have always said that if those scientists who claim that salmon farming impacts on wild salmon are so convinced by their science then they should be willing to argue their case face to face with those who believe otherwise, not with lawyers.

Legal sense: Meanwhile in Canada, the Federal Court of Canada has rejected attempts by anti-salmon farm activist Alexandra Morton to influence its pending decision on the future of the Discovery Island salmon farms.

Sea West News reports that Judge Mandy Aylen has said that ‘Morton’s proposed affidavit contains untested hearsay evidence, contains improper opinion evidence under the guise of being factual evidence.’ The judge also said that the affidavit constitutes an attack on the science presented by the Department of Fisheries and Oceans. One of the lawyers remarked that the court has reminded Canadians that Alexandra Morton’s claims are not to be believed.

It cannot be too long before politicians, regulators and the public recognise that much of the criticism of the international salmon farming industry can be characterised in exactly the same way as by Judge Aylen. Let us now hope that common sense prevails.