Sweaty Betty: According to the BBC News website, the Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, held a video conference with Conservative MPs from coastal areas and backed calls for a campaign to encourage people to eat British-caught fish to help combat post-Brexit disruption. It is somewhat astonishing that Mr Johnson did not tell his MPs that the Department of Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (DEFRA) had already partnered with Seafish for such a campaign and this was due to begin on the first of March. Perhaps Mr Johnson’s failure to mention the campaign was simply that he did not know anything about it.

Mr Johnson may have heard of one other recent attempt to promote British-caught fish to consumers as the story appeared widely in the media. Early in February, it was announced that Cornish fishermen are to rename two of their biggest exports in a bid to stimulate demand at home. Having researched the market, the Cornish Fish Producers Organisation (CFPO) decided to rename the flatfish, megrim as Cornish sole and spider crab as Cornish King crab. Both species are described as being under-loved in the UK but favoured in parts of Europe. It is suggested that about 1,000 tonnes of megrim are landed at Newlyn of which 98% was previously exported. About 85% of spider crabs are exported to Spain.

Paul Trebilcock from the CFPO said that their investigations had revealed that simply renaming megrim as Cornish sole had encouraged more people to try it or that they were more interested in finding out where it came from. It has been suggested that with a bit of a rebrand and a bit of publicity, more of the fish might get eaten at home.

Seemingly the CFPO’s investigations were funded by the Government’s Seafood Innovation Fund (SIF). CFPO joined together with two processing businesses to develop innovative value-added products from two under-utilised species – megrim and the spider crab. This feasibility project was due to last three months and received £29,340 of Government funding. Since the announcement of the plan to rebrand the two species came after the announcement of the second round of funding, of which this project was part, it must be assumed that the main conclusion of the project was to rebrand the two species as Cornish. There is hardly any reference to innovative added-value products but as someone who has been monitoring the retail sector for over twenty years, I would suggest that any such innovation is unlikely to succeed. The number of added-value products outside of salmon, can probably be counted on about two hands. There have been others, but most have failed for reasons too complex to address in a three-month project.

I am not quite sure why the Government needed to spend nearly £30,000 to conclude a rebrand might be the way forward. This would not be the first time that Cornish fishermen have resorted to rebranding in an attempt to develop the market for their catch. Writing in the Guardian, food editor Tony Turnbull pointed out that the pilchard had been in steady decline since the 19th century and was all but killed off by the arrival of tinned tuna until it was renamed the Cornish sardine. Sales jumped by 20% as a result and it soon started to appear on Michelin-starred menus. A recent Waitrose Weekend Food newspaper indicated that landings of Cornish sardines went from seven tonnes in the mid-90s to around 7,000 tonnes in 2018. The latest Seafish data from Nielsen shows that total sardine sales for the last year amounted to 9,725 tonnes up 13.3% from the previous year. Sardines, in terms of their sales value, were in position 13 of the top UK species. These sales include fresh, chilled, frozen and ambient at retail, so the total includes other sardines to those landed in Cornwall such as canned fish. Seafish also produce a list of the top 25 chilled species at retail, which has salmon at number one. However, sardines do not feature on this list which suggests that the amount sold from the fish counter or prepacked is negligible. Perhaps most Cornish sardines found their way to restaurants or were even exported.

Whether volumes are large or not, sardines are available in some UK retailers. This week I saw sardines in prepack form on sale in Marks & Spencer and Morrison’s.

The interesting point is that whilst a couple of years ago they might have been labelled as Cornish sardines, they are now labelled as British sardines with no reference to a potential Cornish origin. Perhaps, rebranding megrim as Cornish sole may not be the answer after all?

As a side point, a local Manchester fishmonger also highlighted the availability of sardines calling them Cornish yet at the same time also using the name Pilchards. It is certainly not straightforward.

One of my first thoughts when I heard about the idea to rebrand megrim as Cornish sole was that unlike sardines, megrim is landed elsewhere in the UK. Last year, 8,033 tonnes of megrim were landed at Scottish ports. Are these fish to be known as Cornish sole too? Certainly, Seafood from Scotland have recently highlighted megrim as an under-utilised fish and promoted a recipe with chestnut mushroom and tarragon sauce.

I was not the only one to consider the implications of renaming a fish by the location where it is landed. Food writer Xanthe Clay also raised the issue in her column in the Sunday Telegraph. She was writing that all the flatfish species deserve a plaice (sic) at the table. She spoke to seafood consultant Mike Warner who said that rebranding megrim would be more of a challenge than for pilchards as megrim is landed across the UK, not just in Cornwall. In response Paul Trebilcock of the CFPO said that the new brand is meant to be just for fish landed in Cornish ports. He added that it is more than just the name but also about defining the fishing boats and the stock being fished. According to Paul, the stock around Cornwall is different to that elsewhere as it has been assessed by ICES scientists as sustainable. That may well be the case, but I would argue that a pronouncement from ICES scientists won’t be enough to persuade British consumers to eat either megrim or Cornish sole.

Xanthe Clay expressed concern that the name Cornish sole is too vague and could be misused. She points out that fish fraud is difficult to prove especially with fillets. She thinks that Cornish sole might be confused with Dover sole, Torbay sole or Lemon sole. Torbay sole is another interesting example of a rebrand using a geographic area to cover up an unappealing name – Witch. Interestingly, I have not seen either Torbay sole or Witch in the retail sector for quite a long time.

In response to Xanthe’s concerns, Mr Trebilcock says that if the name is confusing, then the CFPO will take another look, although the purpose of the rebrand is to take barriers away from people and encourage them to buy more types of British fish. Unfortunately, the barriers are much greater than will be resolved by a simple name change.

It will be interesting to see how DEFRA and the Seafood Innovation Fund (SIF) take forward the CFPO’s plan to rename megrim as Cornish sole. To me, SIF are much more interested in innovative technology than any innovative and disruptive approaches to the marketplace.

Whilst changing the name of megrim is unlikely to boost consumption of locally caught fish, DEFRA have decided to resort to a traditional promotional campaign, which is already underway. This is not the first time that DEFRA have promoted the consumption of locally caught species in recent times. They had planned to conduct a promotion in the run up to Brexit in 2020 but once the pandemic took hold, they opted to run during the first lockdown. This was Sea For Yourself.

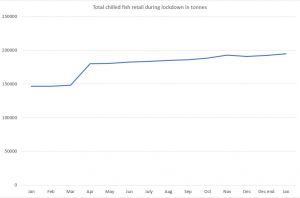

The main focus of this campaign was paid for space in online editions of newspapers such as the Times and the Guardian. These featured those involved in fishing or farming species such as monkfish, hake and mussels. At the time, I expressed concern that these would have minimal impact on consumers and consequently there would be hardly any increase in consumption. DEFRA have not shared their results, so I have used data from Nielsen to compile the following graph of lockdown chilled and fresh consumption.

The graph shows that at the first lockdown, sales of fish for home cooking and consumption soared by just over 30,000 tonnes but since then there have been only small monthly increases. My interpretation of the graph is that established fish consumers, especially those who regularly ate fish out in restaurants but were deprived of such treats, increased their consumption of fish at home instead. After the initial bump up, further increases have been minor, possibly due to small numbers of consumers widening their repertoire to beat food boredom. What is clear is that the DEFRA campaign has had little impact on consumption. It is no longer enough to expect such promotions to persuade the public to change their existing entrenched eating habits.

DEFRA are again partnering with Seafish, although this time through the Love Seafood campaign to help with the task of persuading consumers to eat locally caught fish. In their introduction to the new campaign, DEFRA say that overall annual seafood consumption statistics showed an increase in 2019, which suggests a change to the longer-term downward trend from 2007. They say that according to the latest DEFRA Family Food Survey, UK households consumed an average 161g of seafood per person in 2019, an increase of 5.6% on the previous year. Consumption of 161g per person would be good news indeed but that number does not seem to fit in with the published statistics. The website was last updated on 29th October 2020 with data for 2018/19.

The data for fish consumption from that update is shown in the following table with consumption for 2018/19 at 146g per person per year.

It is unclear how this table relates to the figure of 161g. An increase of 5.6% to take consumption to 161g would suggest consumption the previous year of 154g. Equally, a 5.6% increase on the figure from the table would suggest a current consumption 152.5g per person. Perhaps DEFRA has data that they have yet to share that boosts total consumption to 161g. Of course, these figures are total consumption and not just chilled or fresh fish and seafood.

At the same time as suggesting consumption of 161g, they also say that retailer sales boomed at 11%. Using the Nielsen data, sales of chilled or fresh seafood appear to have increased by a much greater figure of 33%. However, as the press release indicates, this growth, whether 11 or 33% must be offset by the fact that out of home sales have fallen by more than 40%.

This new campaign aims to target several different species including both fish and shellfish. The species identified are listed below and I have added the annual volume sold as chilled or fresh as quoted by Nielsen. The second figure is total volume regardless of whether fresh, frozen, or ambient.

Langoustine – n/a – 89 tonnes

Crab – 740 tonnes – 978 tonnes

Lobster – n/a – 311 tonnes

Scallop – 467 tonnes – 794 tonnes

Oysters – n/a – 63 tonnes

Clams – n/a – 159 tonnes

Mussels- 3,878 tonnes – 4,061 tonnes

Squid – 399 tonnes – 1,569 tonnes

Cuttlefish – n/a – n/a

Turbot – n/a – n/a

Plaice – 1,062 tonnes – 1,567 tonnes

Sole – 1,410 tonnes – 2,651 tonnes

Monkfish – n/a – 108 tonnes

The total volume for these species for 2020 was 12,350 tonnes. By comparison, the total volume for the big five species was 261,656 tonnes. This latest promotion will face major challenges converting consumers from these popular species to these lesser-known target species.

Finally, the news statement about this latest promotion mentions that the campaign will target mid-market families as this group already out-perform other potential target groups. This was the same key demographic as for the Sea For Yourself campaign.

The first marketing activity has appeared this week in the Daily Mail. This is certainly a newspaper that fits in with the mid-market target but at the same time, it is a newspaper whose average reader is aged 58. Seafish have taken out an advert under their Love Seafood brand and my impression is that the advert is adequately tailored to the target age group. It is so traditional and appears very dated, looking as if it has been lifted out of a magazine from the 1950s.

If we are to encourage consumers to eat British fish and seafood, then surely there must be some sparkle and enthusiasm to the message. I have written before that I don’t think it is longer enough to tell people that they need to be eating fish and seafood, we almost need to take them by the hand and force them to do so. I just don’t think that this type of advert will do anything to bring about a discernible boost to consumption.

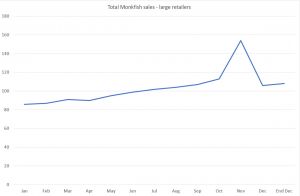

This week that species highlighted was monkfish. Last year, sales of this fish increased by 24% but this was only from 87 to 108 tonnes, an overall increase of 21 tonnes. However, the story is not so straightforward as there was a surge of monkfish sales last November. It is unclear whether this was the result of incorrect reporting or that another event promoted sales.

I accept it is easy to be critical, without offering any alternative suggestions as to how to increase consumption of locally caught fish, however DEFRA/FIS have already rejected one proposal that the UK Government should stop buying the more popular species for use in Government food service, as in Government offices, prisons, hospitals, schools and the military, and only source lesser-known fish instead. Such a change to buying policy could be linked with a weekly Friday fish day promotion in which the only choices of dish served are variations of fish dishes. Why should UK consumers eat fish other than the Big Five if Government is unwilling to take the lead? If the Government wants to support the UK fishing industry it should buy UK landed fish only.

I understand that the budget for the new promotion is in the region of £100,000. I remain unconvinced that the new promotion will bring about an increase in consumption of fish and seafood and especially of the species highlighted. Instead of placing adverts in newspapers and radio, I believe more direct action is needed.

One suggestion would be aimed at shellfish such as langoustine, scallops, oysters, clams and mussels. I just cannot see the average consumer change their behaviour based on being asked to do so. Instead, they need an incentive, and this would take the form of a free tasting, which I would promote through the traditional fish and chip network. I don’t know how far £100,000 would go on giving out free or subsidised products but it could be initiated in one region at first. All the listed shellfish could be battered/breaded to create a mix of ‘Seafood Bites’ and one or two items could be given away free with every order of fish and chips.

Breaded oysters are already big in the US and there is no reason that they cannot be big here either breaded or battered.

Breaded langoustine is just scampi and battered scallops are both available in UK retail.

In addition, a quick search identifies a host of recipes for battered mussel meat including this one from chef James Martin from his Saturday morning TV show. This could equally apply to clams.

Seafood Bites are quick and simple for the fish & chip shop to cook and serve. Whether it is a too simple solution remains to be seen. The Crown Estate has commissioned a £30,000 study of alternative markets for Scottish shellfish from the Scottish Agricultural College. It will be interesting to see what they propose. Of course, this type of promotion does not have to stop with shellfish, lesser-known species such as pouting, ling, whiting could be substituted in fish and chip shops and offered free or at a subsidised price.

Finally, this commentary is titled Sweaty Betty. My local fishmonger recently tweeted that he had one Sweaty Betty left unsold. Although not a fish that is familiar to many British consumers, this is the name under which the Greater Forkbeard is sometimes sold.

According to the BBC News website, Sweaty Betty is a name that will be more familiar to Irish shoppers as this deeper water species is often landed there. It is also landed at Cornish ports where it is known as ‘Plus Fours’.

Perhaps here is another fish ready for a rebrand as neither Sweaty Betty nor Greater Forkbeard will be that appealing to UK consumers. Could Cornish Betty be the answer?