HitLice: The website Aquablogg recently commented on a new paper that had been published in ICES Journal of Marine Science at the end of September. The paper is titled ‘Salmon louse infection reduces condition and induces mortality in wild Atlantic salmon post smolt’ and is authored by David Pioch and his colleagues from the Institute of Marine Research. The research involved a laboratory-based study using wild caught post smolts rather than hatchery fish, as used in previous studies.

The abstract states:

This study confirms the established link between reduced condition and higher mortality due to L. salmonis as observed in laboratory experiments using hatchery reared fish also extends to wild post-smolt entering the fjords underscoring the considerable risk the parasite poses to these populations

In an attempt to compare the infection rates used in this work with those other studies, I wrote to the lead author for clarification of the number of lice used to infect the experimental fish because the in this paper the numbers were expressed in a different way to similar studies.

At the end of his detailed response, he wrote:

Importantly, these infection procedures represent laboratory tank conditions characterized by artificially high encounter rates between lice and fish (e.g., fish agitation and concentrated exposure). This study did not aim to determine infection success rates, and therefore no replicate infection tanks were employed. Consequently, these rates cannot be used to infer broader patterns or ecological relevance, and these conditions are not comparable to infection processes or success rates in the wild.

This response seems to contradict the conclusion reached in this paper but most importantly begs the question that if the work was not expected to be comparable to the infection process in the wild, then what is the point of this research and why are the researchers not working on aspects of sea lice infestation that are related to what happens in the wild, because that is where the alleged issues lie.

Whilst the Storting’s Aquaculture Committee have recommended that there should be a new discussion about the impacts of sea lice, the scientific community still appear reluctant to engage in any examination of the science claiming that they are always happy to discuss any new science but not the older and relevant science that they have always chosen to ignore. It is also easy to understand that there is a reluctance to let go of a narrative that provides the possibility of endless future lucrative research opportunities. For example, the new paper mentioned above was funded through a sea lice project that was awarded last year to the Institute of Marine Research by FHF and the Research Council of Norway.

The project is titled ‘The Hidden Toll of Lice’ with an alternative title of ‘Direct and indirect effects of sea lice’. The project is to cover ‘maths and science, zoological and botanical subjects and parasitology’, which appears to suggest that the maths (models) are more important than any aspects of parasitology. The project is being managed by Ørjan Karslen and runs from 2024 to 2028 with a budget of an eye watering NOK 45 million (£3.38 million). As someone whose budget is more like £3.38, I can only hope that this sort of money would lead to a more open-minded approach to sea lice infestation. Sadly, having looked at the supporting documentation, I think I am going to be very disappointed.

The project description on the FHF website includes a 342-word summary under the heading of: ‘Popular science presentation’, which begins:

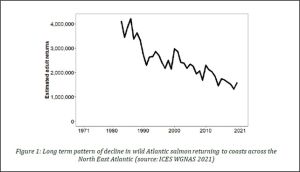

Wild Atlantic salmon are declining across their entire range and are believed to be at historically low levels. In Norway, this coincides with a significant increase in the production of farmed salmon.

The summary starts off well with the correct assumption that wild Atlantic salmon are declining across their entire range and are believed to be at historically low levels but then loses all credibility by suggesting that in Norway, this decline coincides with a significant increase in farmed salmon. This begs the question that if wild salmon are declining across their entire range, then what is causing this decline in areas where there are no salmon farms.

The summary also assumes that correlation implies causation. This is an example of ‘questionable cause logical fallacy;’ in which two events occurring together are taken to have a cause-and-effect relationship. There is even a Latin phrase to describe this fallacy – ‘cum hoc ergo propter hoc’ – ‘therefore because of this’. Yet, this summary provides no proof of any connection between increased salmon farm production and declining wild salmon stocks.

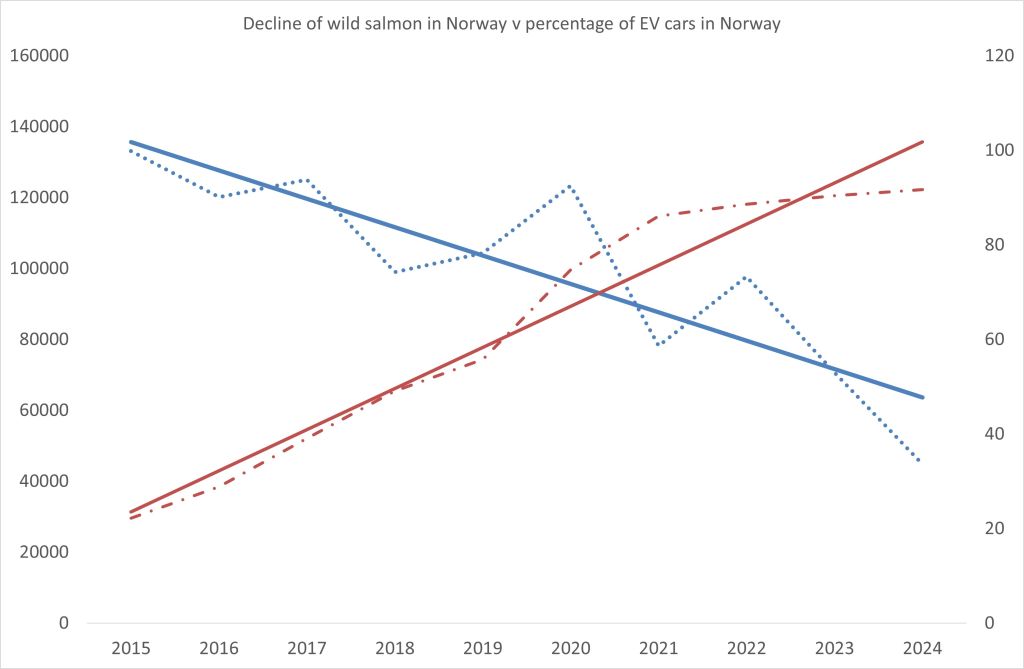

The following graph highlights the fact that the project could be based on a totally wrong hypothesis.

As you can see there is a strong correlation between the decline of wild salmon catches and an increase in the percentage of electric cars on Norwegian roads. Clearly, the Norwegian Government needs to urgently ban the use of electric cars as they are having such a devasting impact on wild salmon numbers. Of course, this suggestion is ludicrous, but no more ludicrous than the assumption that salmon farms are responsible for the decline in the number of wild salmon in Norwegian waters.

The summary continues:

These conflicting trends have led to disagreement as the link between fish farming and wild salmon has become increasingly clear

Of course, the prospect of NOK 45 million of funding has perhaps increased the clarity of this alleged link for those who believe that salmon farming is responsible for the decline of wild salmon. The scientific community are encouraged in this view by the angling sector who are just happy that any responsibility for the declines is deflected away from their own damaging activities.

The project has unnamed partners in Scotland and Canada which is interesting because the usual response to any research from outside Norway is that the conditions in these countries are very different to those in Norway and thus any findings are not applicable to Norwegian salmon.

As Scotland is now included in the research, the following graph which has been widely shared questions the link between sea lice, salmon farming and wild fish declines.

The graph shows that the rate of decline in catches from the Atlantic west coast rivers, where salmon farms are located is almost parallel to the rate of decline of catches from the rivers along the North Sea east coast where there are no salmon farms, nor ever has been. If salmon farming is responsible for the decline in the west, then what is causing a similar rate of decline in the east where there are no salmon farms. This question was posed to twenty-one Norwegian research scientists of whom only one responded.

The reply stated:

You should consider a more directed effort. E.g. gather knowledge about factors that affect the smolt production, quality, timing of run and smolt sizes, and similarly on the return side, e.g. angler effort, spawning biomass, age of fish etc, or maybe a better approach is to single out rivers in the farm intensive side and compare survival of salmon from rivers with farming activity between years, as was done for the Eirriff (sic).

Personally, I believe that fifty years of data provides sufficiently strong evidence that salmon farming is not responsible for the decline in wild fish numbers, especially as Scotland has two very distinct coastlines, one of which has no salmon farms. The response is a typical inconclusive scientific response whereby much more research is always needed. It is also worth mentioning that the link provided in this response to the paper on the Irish Erriff river had nothing to do with the Erriff at all but was Mari Larsen’s PhD paper about the negative association of sea lice on recreational salmon catches in Norway which was based more on modelling than direct evidence.

The author of this email was Dr Ørjan Karlsen, project manager of the ‘Hidden Toll of Sea Lice’ project.

The summary continues:

The most important impact of fish farming on wild salmon is through the spread and transmission of sea lice

Yet, despite many years of research, there is no evidence that sea lice are spread and transmitted as predicted by the various sea lice dispersal models. To date, no researcher has shown that infective sea lice larvae are found in the numbers and locations predicted by the models. However, even without consideration of the models, no-one has found sea lice in the water bodies in any number except in very close proximity to a salmon farm. If the sea lice are not present in the fjords as predicted by the models, they cannot represent a threat to the health and welfare of wild salmon and sea trout as claimed. With such a large budget, the greatest priority of this project should be aimed at finding these lice larvae in open water or else researchers should reject the idea of sea lice dispersal altogether. There are at least fifty species of ‘Lep’ sea lice in European waters and there is no evidence that any find their host by reliance on dispersal using current or wind.

The summary continues:

Although there is no doubt that sea lice infestations harm salmon, the tolerance limits of sea lice in wild salmon are a critical unresolved issue. Knowledge of the tolerance limits of sea lice, mainly based on laboratory studies with farmed salmon, has been the basis for management measures. However, current understanding of the number of lice that cause sublethal effects and reduced survival in wild fish in natural environments is very limited

The reality is there is significant doubt that sea lice infestations harm salmon populations although individual fish can be harmed in some instances. However, just because individual fish can be harmed does not mean that the same harm can be extrapolated to include wild salmon populations. Typically, fish infested with hundreds of lice are seen as the consequence of salmon farming whereas such infestations are not uncommon in nature.

There is also an assumption that high sea lice levels are associated with salmon farming but in a paper by MacKenzie et al. (1998) in ICES Journal of Marine Science (55 151-162) fish were sampled from two sites on the east coast where there is no salmon farming in addition to several sites in the west. One of the east coast sites failed to produce sufficient fish for a representative sample but the site located on the River South Esk provided 57 sea trout samples with a prevalence of 61.4%, the second highest of all the samples of ten fish or more. These fish had a high prevalence of sea lice despite the absence of any salmon farms for hundreds of kilometres.

It is interesting that the summary suggests that the current understanding of the number of lice that cause sub-lethal effects, and reduced survival is said to be very limited, yet an assumption of reduced survival has been part of the Traffic Light System for ten years despite this limited understanding.

The summary continues:

With over 400 salmon rivers in Norway, the only feasible way to assess the effect of sea lice on the survival of wild smolts is to use models.

Interestingly, in his note sent earlier this year, Dr Karlsen wrote that ‘another approach is to do experiments e.g. by protecting some fish against lice’.

The most significant experiment protecting fish against lice was reported in a 2013 paper by Jackson et.al. published in the Journal of Fish Diseases. This seminal work about the impacts of sea lice on wild fish populations has been contentious from the date of publication. This is because the scientific community as well as the angling fraternity have refused to accept its findings because it does not support the established narrative about sea lice.

Jackson states that ‘sea lice induced mortality is a minor and irregular component of marine mortality in the stocks studies and is unlikely to be a significant factor influencing conservation status of salmon stocks.’ Using 352,142 migrating smolts divided into two groups, one treated with an anti-sea lice treatment and a control, Jackson found the difference in absolute terms represents just 1%.

In response to the Jackson paper, four researchers from Canada, Scotland and Norway (NINA) claimed that their analysis of the Jackson data determine that the mortality represents an actual loss of one third of adult recruitment. Their claim received much publicity in the media with reports that a third of wild salmon were killed by sea lice. Yet, comparison of their statistical methodology showed that these scientists were in agreement with Jackson. However, their claims and the media coverage undermined the findings of this work. For example, a review of sea lice science published by Scottish Government scientists does not include reference to this work.

The explanation of how these differences were calculated is simple. Jackson compared the number of fish that returned from the two groups against the number of fish released. Both groups suffered high levels of mortality which reflects the failure of wild salmon to return to their home rivers as tracked by ICES since 1970. The difference in mortality between the two groups was just over 1% overall. The other scientists measured the difference between the number of returned salmon without reference to the number of fish initially released. This was about one third, yet when applied to the background mortality of over 90% a further third would take total morality to120% which makes no sense. However, if the mortality of one third is applied to the portion of mortality out-with the background mortality, the difference is only 1-2% which is largely in agreement with Jackson’s findings. According to the Irish Marine Institute, another paper published in the same year by Norwegian researchers produced very similar results to Jackson.

The question is whether a 1% mortality due to sea lice compared to a background mortality of typically over 97% in 2024 should be the main focus of concerns about wild salmon populations.

It is now twelve years since Jackson published his paper and although there have been other papers published about smolt release trials, most are simply reworking of existing data in order to justify the continued focus on sea lice as illustrated by the award of NOK 45 million for this project. This is despite the fact that it is clear that sea lice do not have the impact on wild fish populations that is claimed.

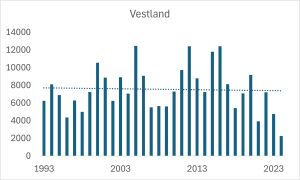

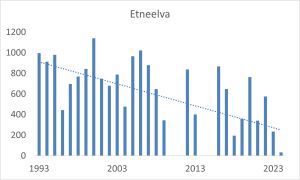

The summary says that with 400 salmon rivers in Norway, the only feasible form of analysis is using models. Yet the project aims to compare the models with amongst other things such as time series of estimated return rates of wild salmon to various rivers. It is unclear whether the researchers already have historic data for such time series or whether they are to generate a new time series for the period of the project. However, what is available is the data of rod caught wild salmon for the period from 1993 for most Norwegian salmon rivers. Scottish Government scientists have for many years used catch data as an indication of the size of the river salmon population with catches representing about 10% of the total stock. Analysing the catch data from every salmon river in Norway will provide an indication of whether local populations are impacted by sea lice and salmon farms. Data from Vestland has already been analysed and the trend over thirty years has been a very slight decline. Given that the number of returning salmon has fallen every year since 1970 a slight decline is hardly a reflection that salmon farms are harming local salmon populations.

This data is the total for Vestland comprising the catch from 31 different rivers of which 12 show a declining trend, such as the Etna, yet the remaining 19 showing an increasing trend of rod caught salmon such as the Leela. Clearly, if two thirds of rivers in Vestland are showing (until now) a positive catch trend, then salmon farming is not having the claimed impact on wild salmon, whatever the models show.

A full analysis of every salmon river in Norway for which data is available is currently underway, but without the benefit of NOK 45 million of funding, this analysis may take some time to complete.

The summary continues:

Accordingly, the main goal of Hit lice is to improve existing models by providing an accurate assessment of the relationship between sea lice and the maritime survival of salmon smolts. To achieve this, field and laboratory experiments with artificial infection of wild fish will be carried out to investigate sea lice thresholds.

Although the FHF webpage refers to the project title ‘The Hidden Toll of Sea Lice’, it seem s that the project also has a working title of HitLice, hence the reference to this in the summary. The FHF webpage however does refer to a separate document ‘HItlice – The Hidden Toll of lice WP3’ as referenced by the Cristin database. The document is in fact a presentation given on 12 June 2025 at NINA by NINA employees. This included the following slide showing that NINA’s involvement in the project is limited to WP3.

Work packages

WP1: Impacts of salmon lice on wild salmon in situ (NORCE)

WP2: Tolerance limits of wild salmon post-smolt to lice (HI)

WP3: External validation: Observed returns of salmon (NINA)

WP4: Reducing uncertainty about population-level effects of salmon lice (VI)

WP5: Perception and communication of the effects of salmon lice on wild fish (Nordlandsforskning)

The summary mentions laboratory experiments using artificial infection of wild fish to investigate sea lice thresholds. It is unclear where this experimentation falls within the listed work packages and how they will be conducted. Thus, at this point in this commentary, reference was going to be made to a Scottish paper concerning artificial infestation of sea trout which is widely cited in the literature. However, an online search has revealed a master’s thesis from May 2025 which is part of the Hidden Lice project. Yet on closer inspection there are actually two master’s theses published about the same work, supervised by the same supervisors published at the same time. Reading the acknowledgements of both these theses suggests that there is a third partner in this work, so it is possible a third thesis on the same topic exists.

In both projects, salmon were artificially infected with sea lice larvae. Both projects aimed for three infestation levels –a control, 0.2 lice/g and 0.6 lice/g, whilst the other thesis aimed for a higher level of 0.35 lice/g rather than 0.6. The concentration of lice at the time of infestation was 5.3 and 16.1 lice /litre in the first thesis and 10.5 and 18.3 lice/l in the second.

By comparison, the highest lice levels found around salmon farms in Canada and Ireland were 0.0014 and 0.0028 lice /l and these fell away to 0.00025 lice /lire within a kilometre of a farm. These are significantly lower than the levels used in the artificial infection theses.

Despite the exposure of these fish to lice being much higher than in nature, the authors of both theses observed no major differences between the infested and control groups. They conclude that at levels around 0.2 lice g fish, the infestation was not high enough to produce a strong physiological response or measurable health impact. Nether thesis supports the claims that sea lice adversely affect the host fish or the suggestion that wild fish populations are negatively impacted by sea lice associated with salmon farms.

This is contrary to the conclusions of the paper that was highlighted at the beginning of this commentary. However, the papers’ methodology must be questioned since the fish used had been living freely in freshwater for 2-3 years, were then caught and transferred to tanks of only 100 litres in volume. Over a period of five days, the salinity was then increased to full strength sea water and then the fish were left for two days before being challenged to sea lice infection. The paper does not say exactly how many lice were introduced to the fish, but fish started to die by day 18. This is not surprising given the treatment they had received since capture. By comparison, the two master’s students used reared fish that were used to being kept in a confined space. Yet, these students did not find the higher morality claimed in the abstract of the Pioch paper.

In 2023, 26 fish were caught from the rivers whilst in 2024, this was increased to 43 although five fish died within days and a further 15 fish showed signs of wounds and tail rot and were removed. This accounts for half the fish in the trial and raises the question whether the remaining fish were in sufficiently good health to ensure that the work represented a true picture of sea lice infestation. Against a background of science that shows sea lice do not have an impact on wild salmon populations, the transfer of wild fish to a laboratory setting was never going to produce any realistic results.

It seems that the Hidden Lice project is just another attempt by the scientific community to try to show that sea lice associated with salmon farms are responsible for the decline of wild salmon in Norwegian waters even though real-life evidence (as distinct from that derived from models) shows that salmon farms are not the cause of these declines.