This is why: I recently attended a virtual workshop on sea lice modelling held as part of the Marine Alliance for Science & Technology for Scotland (MASTS). The session began with the current head of the Norwegian Expert Group who reviewed what we do know and what we don’t know about sea lice and wild fish. I helpfully added to the chat that SEPA had told a Scottish Parliament Committee that sea lice from salmon farms are not responsible for the decline of wild fish only to receive a reply that this issue was not part of the current discussion meaning that it doesn’t matter whether sea lice do or do not impact on wild fish, it is important to model the impacts regardless. In effect, the modelling community are currently working on something for which there is no point.

Meanwhile, one of the industry critics, who was also attending the workshop, helpfully responded to my chat suggesting that I should take note of the summary of the sea lice science which is posted on the Scottish Government website. This critic subsequently wrote that as the Scottish Government now accepts that there is a risk from sea lice, as well as the two members of the industry who attended the SIWG meetings, then isn’t it about time that I too should accept the findings and move on and work out how to deal with the risk. My answer was an unequivocal no.

This is why.

I am not party to Scottish Government discussions, but I anticipate that the reason why the Scottish Government accepts that there is a risk to wild fish from sea lice coming from salmon farms is that they have taken advice form Marine Scotland Science (MSS) who will have written the scientific summary. (https://www.gov.scot/publications/summary-of-information-relating-to-impacts-of-salmon-lice-from-fish-farms-on-wild-scottish-sea-trout-and-salmon/).

I believe that this is the third incarnation of this summary. Long term readers of reLAKSation will know that I have written extensively on these summaries and have questioned whether the evidence presented actually supports the hypothesis that sea lice from salmon farms negatively impact. I have repeatedly tried to obtain an explanation from MSS, but for some reason, they seem extremely reluctant to engage in any discussion about their summary. It doesn’t help that it is not attributed to anyone in particular but remains anonymous.

Before I highlight some of the issues, it is worth mentioning again that SEPA, who have now been given an enhanced regulatory role with regard to sea lice, told the Scottish Parliament’s REC committee that sea lice are not responsible for the declines of wild fish. However, they did say that as wild stocks are now so low, there is concern whether the additional pressure from sea lice could be significant and hence controls might be necessary. What rather grates about this statement, as well as the claim from MSS that the body of scientific evidence shows that sea lice could negatively affect wild populations, is that a seeming blind eye is taken to the fact that in 2020, a year when activity was impacted by COVID, anglers still managed to catch and kill 340 wild salmon and sea trout from rivers in the salmon farming area. All these fish were returning to freshwater to breed and propagate the next generations but were prevented from doing so in the name of sport. Surely, if west coast salmon and sea trout populations are so threatened that the regulators believe it is so necessary to place controls on salmon farming, even though salmon farming is not responsible for the declines, why are anglers still allowed to kill any fish? I would even suggest that if west coast stocks are so threatened, then perhaps the Scottish Government should follow their own example of banning netting and now should ban angling in the area too. After all, the west coast catch represents such a tiny proportion of Scottish angling, that its absence would hardly be noticed.

The summary of science concludes that the body of scientific information indicates that there is a risk that sea lice from aquaculture facilities negatively impact populations of salmon and sea trout on the west coast of Scotland. It says that the science presented includes observational experimental and modelling studies. Of these, clearly the observational studies are most important as these will show whether the wild fish population is actually being impacted by salmon farming and not just some theoretical concept, plenty of which seem to abound when it comes to salmon farming.

The observational studies consist of just three references, two of which I have covered previously, Vøllestad et al 2009 and Ford & Myers 2008, neither of which actually demonstrate that salmon farming has a negative impact on local fish populations. I am still waiting for anyone to explain to me why my view is wrong.

The third paper is by Butler & Watt (2003) who found densities of juvenile salmon to be lowest in west coast rivers near salmon aquaculture sites.

Any confidence in the interpretation of this paper is initially dented by the fact that the reference given to this paper in what is after all a short summary is incorrect. The reference given is actually for a paper by James Butler from 2002.

The paper by Butler & Watt paper is from a book titled Salmon at the Edge which is a report of the Sixth International Atlantic Salmon Symposium organised by the Atlantic Salmon Trust and the Atlantic Salmon Federation. At the time both Butler and Watt were working as biologists for local Fisheries Boards and Trusts. I have previously corresponded with James Butler who now lives in Australia but as soon as I posed any questions, he cut off communication.

The premise of the paper is based on the analysis of data collected as part of regular survey work of 38 rivers from along Scotland’s northwest coast, none of which were deemed to be in catchments in which farms were absent. Of these 38 rivers, Butler and Watt identified 14 of which five had lost their salmon stock and the rest were threatened with loss. Of these rivers, twelve are under 7 km in length (One of 1km, one of 2km, one of 3km, three of 4km, four of 5km, one of 6km and one of 7km). The remaining two rivers were 11 and 23 km in length respectively. The five rivers with lost populations were either 4 or 5 km long. I might suggest that these rivers might be better described as streams or burns but of the 14, only six get a mention in the last edition of Bruce’s Sandison’s Angler’s Complete Guide to Rivers and Lochs of Scotland. One of those mentioned in the River Lael, a short river of 3km which enters the sea at the head of Loch Broom.

There are two farms in Loch Broom, of which has been operating since 1979 and the other since 1984. According to Butler and Watt, their study indicates that where marine salmon farms have been located in sea lochs with salmon rivers, they have exacerbated declines of local wild stocks. They add that because most sea lochs are occupied by salmon farms, their data shows that most wild stocks will have been adversely affected. This will include the River Lael.

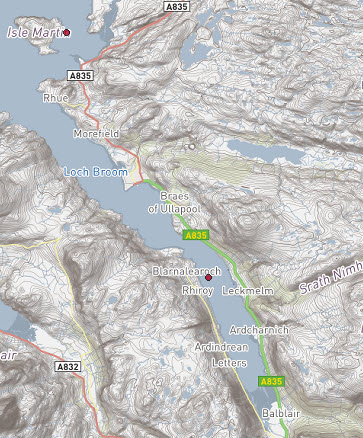

The image below shows the head of Loch Broom and the River Lael flowing down from the bottom right-hand side and thus clearly impacted by the presence of the two salmon farms.

.

However, Butler and Watt’s argument somewhat falls down if other rivers in the area are considered. The Lael is not the only river to enter the head of Loch Broom. The River Broom enters the loch from the south just metres away from the Lael.

The River Broom was classified as an A class river in 1995 and its salmon stock is not considered under threat by Butler and Watt, yet the river’s salmon pass the same farms as those from the Lael. Bruce Sandison recommends the fishing in the river saying that about 50 salmon are caught each year. Since the salmon farm arrived in the loch, anglers fishing the district have caught and killed 2,595 salmon and sea trout from what are short spate rivers. If the numbers are diminishing, perhaps, over-fishing might be to blame, but this would never have been considered by Butler and Watt due to their work in the wild fish sector.

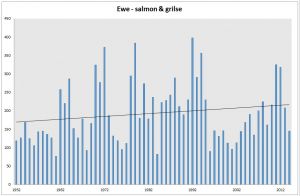

Butler and Watt’s argument also falls down when considering that currently, despite record levels of farm salmon production, 30% of Scotland’s Grade One rivers are located within the Aquaculture Zone including the district with the most contentious salmon farm in Scotland Loch Ewe, although recently closed down as a sop to the wild fish sector. Since the farms arrived in Loch Ewe, anglers have caught and killed 9,568 wild salmon and sea trout from the river and associated freshwater lochs. In the case of salmon, catches have actually increased, not declined.

How can this be when sea lice from the salmon farm, which according to James Butler in his 2006 paper with Andy Walker was responsible for the collapse of the Loch Maree sea trout fishery.

The reality is that the narrative against salmon farming doesn’t hold up when observational studies are properly considered. This is why no-one from MSS or the wild fish sector are prepared to sit down and discuss what these observations really mean. Afterall, it is what is actually happening in Scotland’s rivers that matters not whether some predictions meet some modelled outcome.

The summary of science also refers to experimental studies. These are primarily smolt release studies where half the fish are treated with an anti-live medication and the number of fish returning is compared with those that received no treatment. The summary refers to four studies although only two are actually experimental. The other two use different statistical analysis on the same data in the hope of deflecting attention away from the actual findings. It is interesting that the summary refers to the 2011 paper by Dave Jackson and others when it is well known that he published more detailed findings in 2013. The later paper received much criticism because it did not support the view that sea lice were having a deleterious impact on wild salmon. At the time, the Irish Marine Institute released a video explaining their findings and the criticism. The findings of the study in which 352,142 smolts were release, was that mortality due to sea lice is a minor and irregular component of marine mortality and unlikely to be a significant factor influencing the conservation status of salmon stocks. The level of sea lice mortality is small as a proportion of the overall marine mortality, which is in the region of 90% (now over 95%) and in absolute terms represents 1% of the stock. Of course, a 1% mortality due to sea lice was unacceptable to those who have criticised the salmon farming industry but that is all it is. It is interesting that Jackson’s findings have become lost in MSS’s assessment of the experimental data. Jackson’s findings also matched those of the Norwegian study also mentioned, but not highlighted, in the summary. The Irish Marine Institute video can be watched at https://vimeo.com/83845976.

MSS also mention their own attempt to measure the impact of sea lice on wild salmon, using wild smolts. The £600,000 project failed with not a single fish being recaught. The summary refers to a subsequent study using the infrastructure of large dams to recapture the returning fish. The work which is referenced is published in an MSS report which, as I highlighted recently, is not peer-reviewed and is therefore not relevant to this summary.

Finally, the third type of study are those involved in modelling. Any modelling is as good as the assumptions made in drawing up the model and in the case of sea lice models, the assumption is that sea lice have a negative impact on wild fish, something which yet has to be proved.

Modelling has always been contentious when applied to salmon farming. Campaigner Vivian Krause highlighted the inconsistencies of some early modelling by Martin Krkosek in Canada. A paper was published which predicted the extinction of wild pink salmon due to sea lice from salmon farms. The paper was widely publicised as demonstrating the negative aspect of salmon farming even though the results of the study did not actually prove their predictions. In fact, one of the salmon farms highlighted was actually empty of fish and therefore could not be a source of the lice predicted by the model.

More recently, an expert panel of international scientists have criticised the model on which the Norwegian Traffic Light system is based. The full results of their investigations have yet to be published but they are relevant as a new predictive model of the impacts of salmon farms is being prepared for use as part of the new regulatory system, even though the Norwegian model has played a significant part of its design.

Whilst MSS say that the body of scientific information indicates that there is a risk that sea lice from salmon farms negatively affect populations of wild salmon and sea trout, I would suggest the opposite. I am happy to be proved wrong, but this would involve MSS actually being willing to discuss their conclusions.

I would like to end by mentioning SIWG again. The Ministerial response to SIWG which was recently published stated that amongst other things the group was tasked to:

Although this task seems not unreasonable, the reality is somewhat different. In the case of the ECCLR Committee, evidence was collected from just one member of the salmon industry compared to eleven others. The REC Committee enquiry was initiated through misleading information and requests from at least two committee members for additional witnesses was rejected.

However, my biggest concern is that the literature review undertaken by SAMS covering sea lice was written by an expert on genetics and not an expert on sea lice. It leaves much to be desired. Lastly, SIWG refused to accept any other submissions about the environmental impacts of salmon farms despite being part of the brief. As opponents to salmon farms outnumbered industry on the group, the outcome was inevitable. I would mention that I raised these points even before SIWG first met and during the series of meetings especially when the summary of science was highlighted as proof that salmon farms have a deleterious impact on wild fish.

SIWG was supposed to be the first of a number of working groups looking at the pressures impacting wild fish, but this continued focus on salmon farming means that the other pressures remain in the background. I would ask for example, why is it that around 5.9 million wild fish killed for sport since 1952 Is not considered to be a factor in the decline of wild fish?