Zoned out: A leading angling magazine publishes the fishing reports for rivers around the British Isles. A recent report for Wester Ross on Scotland’s west coast suggested that major issues with sea lice persist in the area. The local fishery trust carried out a sweep netting session at Gairloch and caught thirty-two finnock and young sea trout. The average estimated lice count on these fish was 98 lice per fish – range 16 to 340 – but the majority of these lice were the tiny chalimus stage, which is not unusual in such numbers. The larger female stages averaged just 0.38 per fish.

The fishing report highlighted that the nearest active salmon farms were in Loch Torridon, no more than 15 miles by sea from the sweep netting site. The report says that this is well within the ’32 km‘ zone established by Scottish Government scientists in which salmon farms can allegedly affect wild fish with sea lice infestations.

Over the years, it seems to have become accepted practice to link lice infestations on wild fish with activity and proximity to local salmon farms. Local fishery trusts along the west coast regularly conduct sampling by sweep netting every year. From 2003 to 2009, sea lice counts, recorded by the fishery trusts, were treated to a number of mathematical calculations by Government scientists. The conclusion of this research was that salmon farms exert an influence on the infestation of wild fish up to 31km from any salmon farm. The completed study was published in 2012 and subsequently, it seems to have become accepted that wild fish are at risk from salmon farms located within this 31 km zone, as was highlighted in the recent issue of the angling magazine.

Even though the description of the 31km zone appears in a published scientific paper, there have always been some concerns as to its validity. Firstly, there are different interpretations as to what the 31km zone means. Some scientists see it as a high-risk zone where the risk is the same whether fish are 1km or 31km from the nearest farm. Others see it as an area beyond which there is no risk whilst a third interpretation is that there is a graduated effect which diminishes further away from the farm.

Secondly, larval sea lice are not motile, but drift with the currents and winds. Clearly, if the current flows towards a farm, then that farm is unlikely to have an influence in the direction from which the current flows. Farms could be located close to rivers with migratory fish but have no impact on the wild fish at all. This 31km zone may therefore be too generalised and not relevant to large parts of the west coast. However, this has been just an assumption, at least until now.

The bumper harvest of sea trout last year from the River Polla has meant that the relationship between lice counts on wild fish and the proximity of salmon farms has had to be revisited. Sampling of wild sea trout caught from the Polla and the nearby Kyle of Durness on Scotland’s north coast raised questions because of the number of fish found to be carrying high lice counts. This might have been expected from the Polla which is close to salmon farming activity but the Kyle of Durness is situated more than 31km from the nearest farm. Lice counts should therefore be expected to be low, yet they were not. Something is clearly not right.

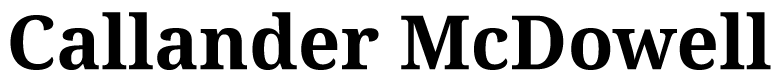

From 2011 to 2015 the various fishery trusts, under the auspices of the Rivers and Fisheries Trusts of Scotland (RAFTS), collaborated to produce an annual report of lice sampling on sea trout covering 28 different sites of varying distances from the nearest salmon farm. These sites ranged from 2km away to 50 km from a salmon farm. In total four sites are located outside the 31km zone and if the original scientific paper is correct, then over the five years of the study, the distant locations should be recording fewer lice than sites situated nearer a farm.

The RAFTS study records different stages of lice development from Chalimus, to pre-adults and ovigerous females as well as total lice. For each of the four groups, the prevalence, abundance and intensity of lice has been documented. In total, there are twelve different sets of data. Each one has been plotted on a graph but unlike the graphs displayed in RAFTS report, the sites have been arranged in increasing distance from the nearest farm, although not actually representative of the exact distances involved – but they don’t need to be.

What is clear from all twelve graphs (the one shown is prevalence for total lice) is that no pattern is apparent. The sea lice count looks relatively similar regardless of the distance of the sample site from the nearest farm. Lice appear to be found in relatively high numbers on wild fish irrespective of how far the sampling site is from the nearest farm.

What seems to have been forgotten is that sea lice infested wild salmon and sea trout long before salmon farming came to Scotland. There has always been a background level of lice in the sea. Unfortunately, in the rush to link sea lice to salmon farming, it seemed to have been assumed that any lice on wild fish must have come from a farm, and not from the general environment. The fact that sampling is only conducted in the salmon farming areas simply re-enforces this preconception. A study from 2010 in which lice were counted from both east and west coast rivers found higher counts in the east.

Finally, does the sweep netting reported this year from Gairloch indicate that issues with sea lice continue to persist or are they simply a reflection of the natural processes that happen in the wild? In all likelihood, the sweep netting has caught weakened fish that may not usually survive. Weak fish then become easy targets for lice, which is why counts can be so high. By comparison, healthy fish are extremely adept at escaping sweep netting so the sample is inevitably biased towards those fish which in the past, have supported the view that salmon farms are responsible for the decline of wild sea trout and salmon.

One river proprietor in the north used to make regular demands that the local salmon farm be moved so that it was at least 31km away from the river. The farm is still located in the same position yet the nearby river was given the highest conservation status of Grade 1 in 2017.

The concept of a danger sea lice zone of 31km around salmon farms resulted from a mathematical calculation in a scientific paper but like much of the sea lice research, seems to have little relevance to what actually happens in the sea.

Bass level: A independent consultant from France has explained to Undercurrent News.com that sea bass and sea bream farming are stuck in the price doldrums. The reason given is that rising production has caused ex-farm prices to plummet by 60% between 1990 and 2000 and continue to decrease.

In addition, the consultant Herve Lucien-Brun says that falling prices have been complicated by attempts to destabilise prices to force some producers out of business. This could even involve deliberately dumping product to reduce competition through enforced bankruptcy.

Overall the number of companies producing marine fish in the Mediterranean Sea has fallen from 430 firms to less than 40 today. Some of the larger companies are vertically integrated with hatcheries, feed mills and processing plants. These companies have been investing in a number of developments with the aim of improving marketability of bass and bream. Mr Lucien-Brun says that this includes developing brands, identifying the country of origin and producing larger sizes as well as investing in Value Added Products.

This all sounds very familiar to us at Callander McDowell. It is reminiscent of the salmon industry in the late 1980’s and early 1990’s. Volumes increased and prices fell, to levels never considered likely for what was perceived to be a luxury fish. The industry had changed from low volume – high margin to an industry of high volumes and low margins. Salmon farming needed to change overnight from a production led industry to one that was led by the market. The big change needed was a move from believing that consumers wanted whole fish to the realisation that what was actually needed were fillets and portions.

This is equally true for bass and bream but to make it work, there needs to be recognition that the future lies with much larger fish that can be more effectively cut up into portions. As Mr Lucien-Brun reports, there are some companies that have started to adopt this approach but it is not enough.

Single portion whole fish are far too small for cost effective filleting and portioning. Fillets are often 90g in size including skin. This is hardly a couple of mouthfuls. The wild sea bass that chefs prefer offer much more flesh on the dish and it is this fish that the industry should try to emulate.

Once a significant volume of large fish comes to market, the potential exists to diversify into a much wider range of products that consumers actually want.

In the UK, research has shown time after time that sea bass and sea bream is not popular like salmon and cod. Consumers do not like to be served a whole fish complete with head, eyes, fins skin and scales. They much prefer a bone free portion of pure fish flesh. This is what the sea bass and bream industry should be producing not a whole fish that consumers don’t want to eat.

Hook, line & sinker: The Guardian newspaper reports that celebrity cook and TV personality, Hugh Fearnley Whittingstall is fronting a campaign to persuade the Marine Stewardship Council to change the way that they apply their certification to tuna fishing boats.

According to Hugh Fearnley Whittingstall and a coalition of scientists, retailers, politicians and campaigners, consumers of tuna from the world’s biggest fishery are being betrayed over its sustainability.

Fishing boats harvesting the Western and Central Pacific Fishery, which provides about half the world’s skipjack tuna, some of which is certified as sustainable, can apparently fish using unsustainable methods whilst on the same fishing trip. This is deemed unacceptable by the new ‘On the Hook’ coalition.

Professor Callum Roberts, a leading fisheries expert said that the MSC are betraying the trust of consumers and duping them into buying what they believe is truly sustainable tuna. The coalition polled UK consumers and found 77% who were aware of the MSC believe that boats should meet the MSC requirements at all times.

What interests us, at Callander McDowell, is the coalition itself. We can fully understand their views but we are more concerned about the coalition itself. They have a website, on the hook.org.uk where visitors can show their support by sending a message to the MSC, however what visitors cannot do is contact the coalition as no contact details are provided. In fact, there is no information at all about those behind the coalition nor how their lobbying is funded. In our view, such lobbying should be fully transparent with any declaration of their interest. The cause may be noble but the motivation behind it may not.

The salmon industry has over the years acquired a bad reputation, mostly unjustified, through campaigns, the motivation for which has been completely hidden as has the identity of those who are pulling the strings.