Down the pan: Intrafish report that average household spending on fish in Japan fell by 6.3 percent year on year making it the eighth straight month of decline beginning August last year and reaching a low of 8.3 percent last December. This compares with overall Japanese household expenditure for March of just 1.3 percent.

The fall in spending is being attributed to a worrying shortage of fresh fish due to poor harvest in both Japan’s coastal water as well as from more distant fishing grounds. Out of twenty-one categories of fresh fish and seafood only two, yellowtail and Pacific saury, a member of the mackerel family, showed any increase. The biggest declines were crab (down 54%), squid (36%) and red sea bream (26%). Spending on fresh salmon fell by 17.8%.

We, at Callander McDowell, were surprised by this report because whilst Japan does catch some Pacific salmon commercially, any shortages could quickly be supplemented by imports of farmed fish. We wonder whether the fall in spending and hence consumption could be the result of other factors aside from a shortfall in catches.

We have previously written about changes to consumption of fish in Japan. Only last year, reports from Japan suggested that fish consumption had fallen to levels not seen since the 1960s. According to Government figures, consumption of fish in Japan in 1964 were about 25.3kg per head. As the national economy grew in subsequent years, so did fish consumption peaking in 2001 at 40.2kg. Since then Japanese consumption of fish and seafood has been in long-term decline falling to 27.3 kg per head in 2014.

One of the biggest groups to forgo fish are the younger age-groups who have rejected fish in favour of burgers and fried chicken. According to the Financial Times, imports of Chilean salmon have fallen as well as other previously popular species such as tuna. It is not just local supplies that are less available.

Older age groups, more used to the traditional Japanese diet, are also turning away from fish because they think it is too fiddly to prepare

The newspaper suggests that the decline may be the result of a westernisation of the Japanese diet to include more meat and dairy. In 2006, consumption of meat overtook that of fish.

In fact, Japan is no different to many other ‘western’ nations in that consumption of fish and seafood at home is in decline. The past image of a nation eating a diet rich in fish is disappearing into history and that may not be happening just to Japan.

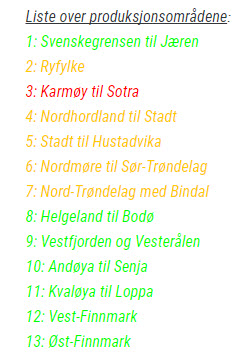

Traffic’s running fine: Fish Farming Expert reports that the threat to wild salmon smolts in Norway is mainly low. The expert group on the impacts of sea lice on wild salmon have found a low risk of mortality on wild in seven of the country’s coastal production areas, a moderate risk in five and a high risk in just one. This preliminary conclusion was derived from ‘solid international knowledge’ and results from models and monitoring data from 2016. According to the group, the conclusions considers the biological conditions of both the fish and lice, in addition to physical conditions such as current and temperature and is professionally well-founded.

We, at Callander McDowell, are not overly impressed. It seems that after all the work to assess the state of the coastal areas, only about 7% of the coast is considered to be at risk. The rest of Norway’s coastline represents a mainly low threat to wild salmon. This supports our view as expressed in the last issue of reLAKSation that the biggest risk to wild salmon is from the scientific institutions, most of which seem to have a preconceived view of the impacts of salmon farming on wild salmon. These first results of the new order don’t seem to support their view.

We were interested to read the associated comments from the expert group that the conclusion is based on solid international knowledge and is professionally well-founded. It seems that they are almost having to justify themselves that their findings are correct, not something that most experts feel they have to do. After all, they are experts.

Norway’s Ministry of Fisheries is expected to implement the new traffic light system after the next report is issued later this year. However, we would be worried about their advice since the scientists in the expert group admit that research involving wild animals and oceans currents, like weather forecasting is not always 100% accurate. They say that the main uncertainties relate to the allocation mechanisms for salmon lice, emigration time and salmon migration routes, all of which can have a significant impact on the subsequent infestation rates on smolts. This seems to us to be a major deficiency in the knowledge of natural infestation especially given the huge body of research on sea lice. It seems that questions of whether the salmon industry can expand or not depends on many ifs and buts.

The expert group admit that more data is needed in order to reduce uncertainties, something which must be of concern if the traffic light system is to be turned on soon. We are also concerned that the group also admit that more research is required in advanced mathematical modelling. As yet, it seems that the group are unable to even work out from which rivers the smolts they catch originate. Instead, they use a mathematical model, no doubt built with preconceptions and assumptions.

Finally, the group say that there is still uncertainty around the threshold values used to quantify how high mortality differs according to the number of lice involved. Attempts to validate the model are still under development but the group want to reach a point where it can be quality assured and published in scientific journals (see later).

To us from outside Norway, the traffic light system is not the solution. We are not even sure that the problem is sufficiently defined. However, if there is one thing that stands out as being wrong about this new proposal is the expert group itself. Yes, it includes people from a variety of institutions but the real deficiency is that there is not one single person included from the salmon industry, which after all is the target of the group. The salmon industry employs plenty of well qualified scientists, why are they not represented? In our opinion, it seems that this expert group, together with their preconceptions are being left without checks to dictate the future of salmon farming in Norway.

End of the Pier: The Times newspaper has highlighted a University prank that has embarrassed academia but has been deemed hilarious by the public. A philosophy professor and a mathematician made up a learned paper, the title of which is too conceptual to mention but it was stuffed full of random jargon and fake references. To the authors surprise the paper passed through peer review and was published. They had felt that the paper should have bene unpublishable in all peer reviewed academic journals. This is not the first time that an absurd paper has been accepted for publication. The authors believe that the reason that both papers were accepted was that they fitted the prejudices of much of academia, such as leftist, post-modern, relativist, feminist and moralising.

Matt Ridely writing in the Times argues that ‘peer review’ is in deep trouble. He says it allows established academics to defend their pet ideas and reward their chums behind a veil of anonymity., which could hardly be better designed to ensure cronyism. Worse still , a journal’s decision to publish a paper provides no assurance that its conclusions are sound. Matt Ridely says that while science is supposed to be self-correcting, the process by which this occurs is haphazard and byzantine. He continues that the flaws in the peer review system now allow people with an axe to grind to dismiss even the most rigorous and careful science along with the nonsense. Matt Ridely says that it is time for science to get its house in order.

We were reminded of the power of the science paper when in the same issue of the Times, their countryside correspondent highlighted the ‘Fish farm parasite plague lays waste to wild salmon’. This was an article about the paper recently published by Samuel Shephard and Paddy Gargan from Inland Fisheries Ireland about which we have already written. The study found that numbers of returning salmon were more than 50% lower in years following high lice levels on nearby salmon farms. According to the Times, the scientific paper was published in the Aquaculture Environment Interactions.

We, at Callander McDowell, have read through the paper and as it is focuses on statistical and mathematical modelling, it is beyond our understanding. Like most people, we have to rely on the abstract and the accompanying IFI press release to learn of the findings, even though we are unable to check them. In fact, most scientific papers relating to sea lice and wild fish interactions are based on these mathematical models. Even the traffic light system proposed for control of sea lice in Norway relies on such modelling. This is the specialisation of a small group of researchers, who probably peer review each other’s papers. It is only necessary to look through the reference list to see that they often collaborate on their research. This is almost a closed shop and which is why it can be so difficult to proffer a different view. We have written previously about our experience at an ICES workshop about sea lice that took place last year in Denmark. We didn’t feel it was a forum for exchanging new ideas rather conformation of the work of this small group.

We would like to make it clear that we are not insinuating anything about this small group of scientists or their research into sea lice. However, it is possible to show how they interconnect as we noticed that the journal in which Sam Shephard’s and Paddy Gargan’s paper appear is edited by Bengt Finstad. This fact appears after the references at the end of the paper.

Dr Finstad, who also attended the ICES workshop referred to earlier, works at the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research in Trondheim, one of the agencies who are involved in the proposed traffic light system for the control of sea lice in Norway. In fact, Dr Finstad is part of the expert group on the impact of sea lice. Bengt Finstad has also worked with Paddy Gargan co-authoring at least nine papers since 2005 as stated in his CV.

We, at Callander McDowell, may yet submit our latest research to the journal Aquaculture Environment Interactions. We wonder whether it would be published as it contradicts some of the findings of established sea lice thinking.

Meanwhile, we were interested to see that whilst Inland Fisheries Ireland have been quick to suggest that salmon farms can cause a 50% reduction in runs of wild Atlantic salmon, they are also happy to post pictures of anglers holding dead salmon caught from the Erriff as well as detail the catches (http://fishinginireland.info/news/salmon-reports/recent-rain-improves-fishing-on-the-erriff/0. We saw the following on IFI’s Twitter account.

Whilst the study relies on mathematical and statistical modelling to draw its conclusions, by comparison, we don’t need any more proof of the impacts of angling on wild stocks as can be clearly seen.