What a week: I maintain a list of news stories about which I think are worth a commentary. My plans have been thrown out of the window more than once over the past few days. It’s been quite a week. Last Saturday, Salmon & Trout Conservation published a report in conjunction with the Sustainable Inshore Fishery Trust in which they questioned the way in which the economic success of salmon farming is judged.

On Wednesday, Marine Scotland Science published (rather quietly) the statistics for wild salmon and sea trout catches for 2019 by rod and line.

On Friday, the long-awaited report of the Salmon Interactions Working Group was published.

Each is worthy of a lengthy commentary. In fact, I was prompted to write my response to the S&TC shortly after it was published but as an editorial in the Press & Journal has already criticised the report as ill-judged, so given other events, I’ll just restrict my comments to one part of the report which I’ll discuss later in this commentary.

The publication of the catch data was not the subject of the usual Scottish Government press release this year. I suspect that the Scottish Government have more important concerns at present as to the fact that wild salmon catches have increased by nearly 28% over the previous year. Sea trout catches have increased by 23%. The Courier newspaper seems to be the only newspaper to have picked up on the statistics with the headline ‘Calls for urgent support for fisheries as coronavirus and low salmon population put industry in crisis.’ The article quotes Dr Alan Wells of Fisheries Management Scotland saying, ‘Salmon catches in Scotland remain at historic low levels and there is now a collective recognition that this iconic species is in crisis.’

Dr Wells has been active in the Salmon Interactions Working Group trying to reduce the alleged impact on wild salmon from salmon farming. Perhaps, he should have been directing his attention towards his own industry for whilst the number of salmon that have been released back into the rivers in the hope that they will breed has increased by 26% compared to 2018, the number of fish kept and killed for the pot has increased by a ‘staggering’ 53%. For sea trout, the number put back has increased by 20% whilst the number killed and kept for the pot increased by another ‘staggering’ 51%.

The Courier article included a reminder that last December, one of Dr Wells’ constituent organisations, the River Tay District Salmon Fishery Board asked its members to support a call that all fish caught from the River Tay during 2020 should be returned. 52% of the members supported full catch and release, however, the board did not pursue the matter as they felt they did not have a strong enough mandate. I remember at the time drawing a parallel with the Brexit vote which attained a similar 52% yes and this was considered sufficient to take the UK out of Britain. Obviously, river proprietors think differently to the UK Government, perhaps more motivated that their incomes might fall because anglers might be deterred from fishing if they are unable to take a fish home.

Given that Dr Wells feels that wild fish stocks are in crisis, perhaps he should call for a total ban on killing any fish in every river across all of Scotland. It surely is a nonsense to demand that wild fish should be a national priority and then to kill them. Surely, there is no justification for a continuation on killing fish for sport. Salmon & Trout Conservation have also failed to step up to the plate on this issue despite changing their name to include the word ‘conservation’. Of course, what they mean is that they wish to conserve salmon & trout stocks so their members can continue their sport. I am reminded of the words of respected salmon fisheries scientist Willie Shearer, who worked at the Freshwater Fisheries Laboratory at Pitlochry for many years. In his book, Atlantic Salmon (1992) he writes about the buy-out of salmon nets by the rod fishery owners, which he says was a repeat of similar action over a hundred years previously. Dr Shearer wrote that the objective was to increase the rod and line catch and the capital value of rod fisheries. ‘The conservation of salmon does not enter the equation.’ (page 202). This view seems very appropriate, especially in the current climate.

In the official press release accompanying publication of the Interaction Group report, Dr Wells states that ‘ Atlantic salmon and sea trout in Scotland are approaching crisis point and it is vital that Scotland’s Government and regulatory authorities do everything in their power to safeguard these species in those areas where they can make a difference.

Before I pick up on this point I find it puzzling that the Courier reported on April 30th that Dr Wells said that ‘There is a collective recognition that this iconic species in in crisis’, yet just a day later, the Scottish Government press release has Dr Wells saying that wild fish are approaching crisis point. The question is whether wild salmon are in crisis or not. The reality is that the wild fish sector often make conflicting statements, probably because the data they have to support their claims is equally conflicting. This especially relates to the west coast where claims that wild fish are near extinction do not match up with the fact that for this season, 14 rivers have bene classified as Grade 1 and another 20 as Grade 2. These are all rivers that Marine Scotland Science judge can be exploited subject to local rules.

The problem as to whether salmon and sea trout stocks in Scotland can be judged to be in crisis or not is simply down to the fact that the available data is abysmal. The wild fish sector has consistently failed to generate more accurate data simply because they were too busy catching and killing 5.9 million wild fish since 1952 to consider the scientific implications of their actions. They thought the abundant harvest would last for ever and thus there was little incentive to act. Of course, now catches have fallen, it’s a different story with demands to make wild salmon a national priority.

Returning to the Scottish Government press release, Dr Wells says that it is vital for the authorities to safeguard wild fish ‘in those areas where they can make a difference.’

Perhaps, one way to make a difference would be to ban killing of fish for sport. It could be suggested that even more draconian measures could be implemented. After all, the wild fish sector has been ready to call for similar measures against other sectors. Unfortunately, as an Editorial in the Times discussed a year ago, anglers don’t think that they have any impact. The editorial stated that anglers are the one group who are beyond reproach because of the number of fish they now return to the rivers. Thus, clearly stopping fishing isn’t considered as something that would make a difference. Instead, the wild fish sector argue that the one area where the authorities can make a difference is by increased regulation of salmon farming. However, I would ask, what difference will increased regulation of salmon farms make to salmon stocks in the river Tweed which is located nowhere near any salmon farm. About 90% of wild salmon catches are made from rivers located far from any salmon farm. Surely, if Scottish salmon stocks are in crisis, then the focus must be on those rivers with the largest stocks.

Exactly a year ago, following publication of the 2018 salmon catch statistics, the Guardian newspaper visited the River Tweed. The paper spoke to a local ghillie who said that when he took over the beat 40 fish would be caught in the spring. In 1995, three anglers landed 19 in one session. In 2018, anglers caught just two fish. The ghillie said that salmon numbers have ‘gone off a cliff’.

The Tweed Commissioners say that a 60-year cycle in salmon stocks is linked to a meteorological phenomenon called the North Atlantic Oscillation. This affects food supplies out at sea, and these are further impacted by climate change. Extensive monitoring of salmon breeding has shown there is no fall in the number of salmon juveniles but that very few make it back, perhaps only 1%. The Commissioners say that most of the problems they’ve got are out at sea.

Yet, when the paper spoke to Alan Wells about the Tweed, he said that each salmon river faces different challenges. He said that in the north, it comes from hydro-electric that blocks salmon migration. On the west coast they are hit by sea lice from salmon farms whilst inland, pollution from agriculture affects water quality. Addressing any of these is seemingly not going to help salmon numbers on the Tweed.

Yet since 2018, Dr Wells has been involved in the Salmon Interactions Group looking at the impacts of salmon farming on wild fish stocks. This has focused on stocks just in rivers around the north west coast of Scotland. To put this into context, in 1952 long before salmon farming had arrived in the Scotland, catches of salmon and grilse from the area now called the Aquaculture Zone accounted for 15% of the total Scottish catch. More significantly, the 51 fishery districts around the north west coast produced a total catch of 4,808 salmon & grilse. In the same year, the River Tweed alone produced 4,611 fish. That year the Dee produced 5932 fish and the Spey 5035. These rivers are clearly the powerhouse for Scottish salmon and yet, Fisheries Management Scotland have spent the lats eighteen months focussed on trying to control the salmon farming industry. The nonsensical way that Marine Scotland now present the catch statistics means that as yet, I haven’t had the time to see how many fish were caught from around the Aquaculture Zone compared to the rest of Scotland. I will not be able to produce an exact figure because of the way that fishery districts have been amalgamated. I will discuss the statistics and the way that access to what limited data is available has now been restricted in a future reLAKSation.

I have had major reservations about the Interactions Working Group from when it was first announced, and these reservations have been confirmed in the report. After eighteen months of discussion I had expected to see a 70-80-page report but instead the report is just ten pages long. At the top of page 4, the report states that ‘in recognition of the potential hazard that farmed salmon aquaculture presents to wild salmonids…….’. After ten years of researching these interactions, I have yet to see any firm evidence that salmon farming is responsible for declining stocks of wild fish. Disappointingly, the Working Group refused all attempts to present evidence to the contrary. This was not surprising given the wild sectors refusal to engage in any discussion.

Dr Wells said that he wants to see the authorities act to safeguard wild fish ‘in those areas where they can make a difference.’ One of the subjects I wanted to raise was that of the three-mile limit and the role its removal had in the collapse of sea trout stocks in fisheries such as Loch Maree. It would appear that reinstating the three-mile limit, as requested by the creel fishermen, might herald a return of sea trout to the west coast. This would be quite easy to change even if it was just limited to the north west coast on a trial basis. Sadly, Dr Wells wasn’t even interested in my offer to make my case to the now cancelled FMS conference. It might be expected that if wild salmon stocks are in such crisis then the wild fish sector would be interested in hearing any suggestion as to how to improve stocks. Unfortunately, this is not the case and the only interest is in pursuing those areas in which they have a preconceived belief of the problem. This means that salmon farming, despite being located in just one area, well away from the major salmon rivers, is the main target for wild fish sector efforts.

On the 30th May 2019, the Scottish Government published their document on the 12 high level pressures affecting wild salmon. Notwithstanding that I believe that there are other pressures that should be added to this list, I question why there has been no attempt to establish other groups to investigate at least some of these pressures in parallel with the farming group. Even now that the Salmon Interactions Group has finished their deliberation, there has been no announcement as to if and when the other pressures will ever be investigated by this or another group.

The working group document has raised various issues and as it is just fresh of the press, I will wait until another time before I consider the long list of recommendations.

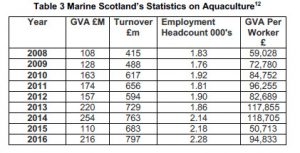

Meanwhile, I would just like to highlight one example from the SIFT/S&TCS report that was published last week. Perhaps, anyone reading this might like to see if they can spot the difference between the two following tables?

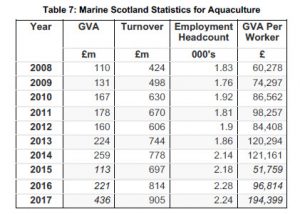

Table 3 appears on page 12 of the newly published report ‘The Economic Contribution of Open Cage Salmon Aquaculture to Scotland’ commissioned by S&TC and SIFT. Table 7 can be found on page 16 of the same report.

The fact that both these tables have been published in the same report raises many questions, not least that prior to publication it would be expected that the report should have been proofed by all three authors. Equally, I would have expected that the report would have been sent to both S&TC and SIFT for approval and most importantly, S&TC have stressed that the report was sent for peer-review by Bridge Economics. It is a complete mystery that no-one has appeared to notice that this data was presented twice in different tables and more significantly, that the data, although remarkably similar, did not match up.

Table 7 is not referenced as to the source of the data. Table 3 is linked to pages of Marine Scotland Science reports covering a whole range of subjects. The only data I could find related to turnover and employee number. There are no reports with data about GVA, so it is possible the authors calculate the figures themselves. It is unclear so I wrote to one of the authors asking for clarification. I have had no response.

In the report, the authors state that ‘It is difficult to believe that the Gross Value Added per employee more than doubled 2016-2017 given a rise in turnover of only 11% and a fall in employment of just 2%.’

I am not an economist and have no specific grasp of the methods employed by the authors. However, I have looked at the relationship between GVA and turnover in both these tables and found that for the eight years between 2008 and 2016 an average figure for the GVA can be obtained by dividing the turnover by 3.6. The authors question the data for 2107, but if the same value of 3.6 is applied then GVA would be £251 rather than £436 quoted and the GVA per employee would be £112,053. This would make more sense with an increase of 16% rather than 100% as the authors calculate. I can only repeat that I am not familiar with how GVA is calculated but based on historical evidence, a multiplier of 3.6 appears to fit the trend for the years shown

The authors have concluded that the available economic evidence is partial, incomplete and unreliable and the data is being used inappropriately!!

The S&TC report, the catch data and the Interactions Group report all merit further comment so these will all be addressed in further issues of reLAKSation.