‘Salmon’: Last week, the Herald newspaper published a long article about the decline of wild salmon. It repeated the same old issues that have been repeated many times elsewhere. What was different in this article was that Mark Bilsby of the Atlantic Salmon Trust recalled being interviewed by Mark Kurlansky, the author who rose to fame with his book ‘Cod – A Biography of the Fish that changed the World’ for a new book on salmon which is due out later this year. The Herald reports that Kurlansky has described salmon as a natural barometer for the health of the planet. Mr Bilsby said that Kurlansky is a North American and he is seeing the salmon problems as we are. These are climate change, habitat loss and urbanisation.

Mr Kurlansky also appeared on BBC Radio 4 Food Programme. He told the programme ‘that to have a prosperous river you have to have a forested bank. He explained that in England during the Industrial Revolution, they completely destroyed rivers; they built dams to power factories and the factories dumped pollution into the water. They chopped down all the trees to build ships but also to build cities and towns along riverbanks. They did all these things wrong and there were virtually no salmon left in England, then some of these people moved to North America’ and did exactly the same thing there.

Mar Kurlansky’s previous works have confirmed that he has a terrific track record of historical research, however his comments to the Food Programme might suggest some confusion about salmon in the UK. The Industrial Revolution was a time of great change in Britain and certainly water powered factories sprang up across the land. The first purpose-built water powered spinning mill was built by Richard Arkwright in 1777 at Cromford in Derbyshire. The mill, together with the village he built for his workers were constructed of stone and much has survived until today. The mill is now a World Heritage Site.

Ships had been made from wood for centuries, but this changed during the late Industrial Revolution when the first ship made completely from iron and powered by steam was constructed. Wood had always been a main source of fuel, but the Industrial Revolution saw a massive rise in the use of coal.

Deforestation in the UK did not start with the Industrial Revolution. ‘Trees for Life’ point out that in Scotland, woodland peaked around 5,000 years ago with coverage of about 1.5 million hectares of the Highlands. Early farmers arrived about 3,900 years ago and they started to impact trees with land clearance and animal overgrazing. By the time the Romans arrived, over half the native forest had disappeared. By the eighteenth century around the start of the Industrial Revolution, woodland cover in Scotland reached an all time low due to agriculture, wood for fuel and ship building. It is therefore questionable whether the Industrial Revolution brought about a decline in the number of salmon in Scottish rivers.

Currently, the rivers producing the best catches in Scotland are those in the north. These are rivers with minimal tree cover. It could be argued that to have a prosperous river, a forested bank is not essential. This link between trees and salmon comes from North America where mass die offs of Pacific salmon after spawning provide the nutrients for tree growth whilst the trees return nutrients that feed the young salmon as they grow in the river. Of course, there are big differences between salmon rivers in North America and northern Scotland, not least their length. The Skeena River in British Columbia flows for 350 miles whilst the River Thurso is less than 27 miles long.

Unfortunately, Mr Kurlansky’s book isn’t available until later this year so anyone wanting a copy will have to wait to find out what Mr Kurlansky has to say about salmon. However, where there is a will, there is a way and I have managed to obtain a copy and an interesting book it is too.

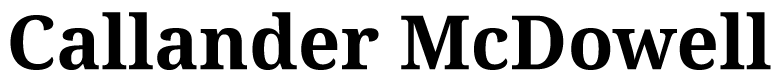

The book entitled ‘Salmon – A Fish, the Earth and the History of their Common Fate’ is a hardback of about 450 pages. The first thing I noticed even before I opened the book was the name of the publisher. This is Patagonia, the same company who have been promoting their film Artifishal about the impact of dams, hatcheries and salmon farming on wild fish. On the first page, Patagonia say that they ‘publish a select list of titles on wilderness, wildlife and outdoor sports that inspire and restore a connection to the natural world’. However, Patagonia’s position on salmon is clear and without even reading a word, the tone of the book might be anticipated. Patagonia Is not Mr Kurlansky’s normal publisher so there is a question whether Mr Kurlansky was specifically commissioned to write the book. Yet, I have enjoyed reading some of Mr Kurlansky’s other books, so I looked forward to reading his latest work.

The first thing that struck me as I flicked through the book is that it is peppered with recipes, mostly historic, but as the book’s prologue focusses on two commercial fisheries, the link with food is established from the outset.

The book is divided into four sections – The fish; How people have interacted with the fish; The problems with solutions i.e. salmon farming and finally; The future. I can see the logic of this arrangement, but it means that the book jumps about from one species to another and from one area to another. Whilst there are clearly some common issues, my view is that the book would have read better if it had been divided into Atlantic and Pacific salmon.

As I have already mentioned, Mr Kurlansky is a skilled historian and has managed to put together a wealth of facts stretching back over a long period of time. Where the book falls down is Mr Kurlansky’s interpretation of how the history impacts on the salmon we have today. For the general reader, this is probably not an issue, but I struggled with some of the detail in terms of what I have heard elsewhere.

For example. In consideration of the future of Atlantic salmon in Scotland, Mr Kurlansky spoke to Mark Bilsby, who was presumably still with the River Dee at the time. He relates that they had tagged fish in the river and 70% did not make it to the mouth of the river and we don’t know why?

In his new role at the AST, Mr Bilsby has overseen the tracking project which has identified that higher than expected numbers of fish don’t make it to sea. This is about two thirds of the fish tagged.

In the book, Mr Kurlansky reports that the about half the sockeye eggs that are fertilised will die or be eaten. A quarter of those that live will survive to be smolts and about eight percent of this will survive to reach the sea. This is very low survival.

It raises a major question. The AST appear surprised that freshwater mortality is around 60%, yet a previous project on the Dee had identified a 70% mortality. Mr Kurlansky suggests a much higher mortality still. Salmon Fishery Boards have been in existence for over a hundred years. Catch data has been collected since 1952. Surely after all this time, we should know what sort of mortality can be expected at each stage of salmon’s life. Why are we only looking now? The answer is simple. Until recently, anglers had enough fish to catch to satisfy their sport so there was little interest in discovering more about salmon’s lifecycle. Now that there are not enough fish for anglers to catch, it is a different story. The problem is that there is no data for comparison, so we have no idea whether 60% mortality in freshwater is low or high. There might be a problem in freshwater but equally there may not.

Rather than focus on this study, the wild fish sector has decided to conduct a similar project on the west coast. Clearly, there is no concept of what sort of mortality can be expected in freshwater in the west. Most attempts of linking mortality to something on the west coast has been to salmon farming. It wouldn’t be surprising if this new study concluded that the biggest issue is farmed salmon. West coast rivers are much shorter than in the east and therefore there are not only less fish but less opportunity to predate. However, without historical data for comparison, there are much better studies which could be undertaken.

As well as highlighting the impact of factories during the Industrial Revolution, Mr Kurlansky points out that the River Spey was seriously damaged by pollution from the growth of whiskey (sic) distilleries. He then goes on to say that some of the earliest hydroelectric dams were built in Scotland, first in Loch Ness in 1895 and then Kinlochleven in 1906. Many more hydroelectric schemes have been built since. Interestingly, hydroelectric rarely features in the conversations about wild salmon declines in Scotland. Mr Kurlansky tells a different story about the US. He says that hydroelectric dams were part of a strategy to develop human activity at the expense of nature. There are plans to reverse this strategy and in 2011, a hydroelectric dam on the Elwha river was removed. Salmon have now returned to the Elwha for the first time in a century.

In Scotland, the Government has produced a list of high-level pressures affecting wild salmon. Interestingly hydroelectric is not one of them. Instead the impacts of hydroelectric are considered within other pressures such as barriers to migration and habitat water quantity. It’s almost as if the issue of hydroelectric has been downplayed in this wider consideration of the impacts on wild salmon. Of course, there is recognition by the power companies that hydroelectric does have an impact on wild salmon as over many years they have worked with local fisheries interests to try to help mitigate such impacts. Interestingly, a representative from the power industry attends meetings of at least one fishery board in a non-voting capacity. However, they may be involved with other fishery boards too, but those fishery boards may not be so forthcoming with such information on their websites. A focus on the aquaculture industry may help divert attention away from the impacts of power generation on wild salmon.

I recently heard that after a year of discussions, the Interactions Group have now held their final meeting. When the Interactions Group was first announced, the Scottish Government website stated:

A Salmon Interactions workstream has been launched to look in part at the reasons behind the decline in wild Atlantic salmon.

The first stage of the Workstream is the creation of an Initial Working Group which will examine and provide advice on the interactions between wild and farmed salmon.

Now that this group have concluded their work, I look forward to reading their report and I would expect that more working groups will be established to examine the other high-level pressures. Unfortunately, I suspect that there will be a massive divide between my expectation and what actually happens. My feel is that, now the wild salmon sector has had their opportunity to express their concerns about aquaculture and be the recipients of the largess of the Big Offer, we will hear no more of this workstream. As everyone knows, salmon farming is the key issue that the wild sector wanted to address.

Mark Kurlansky devotes a whole chapter to salmon farming. It is titled Sea Cattle. In a book published by Patagonia who are clearly against salmon farming, the chapter is perhaps not as critical as might be expected. I suspect that Mr Kurlansky did not delve too deeply into the subject. With respect to salmon farming in Scotland. He writes that ‘In the 1970s, the Norwegians took salmon farming to Scotland’. His usual impressive research appears to have omitted the bit of history where the Anglo Dutch corporation Unilever, through Unilever Research established a hatchery at Lochailort in the 1960s which evolved into Marine Harvest, eventually becoming the company Mowi which we know today. I worked for Unilever Research for a while and heard no reference to Norway at all during my time there.

Following the chapter on farming, Mr Kurlansky turns his attention to angling. This is more observational than critical. Coming from North America, Mr Kurlansky is more aware that in Scotland, salmon angling is a sport for the upper classes, although he points out that the industrial Revolution created a new upper class who were not necessarily high born, who also took up the sport, often following the example of the royal Family.

Mr Kurlansky writes that Scotland has a history of rebellion and warfare but is a society at least with respect to fly fishing, locked down by the aristocracy. He continues that if fly fishing has a reputation as a sport for the privileged, this is where it comes from.

Mr Kurlansky highlights the river Dunbeath and its single proprietor, Tertius Murray-Threipland, who had bought Dunbeath Castle at a bargain price because it was in a poor condition and because the river had been pronounced dead by a biologist. Mr Murray-Threipland told Mr Kurlansky that with the help of a hatchery, he brought the river back to life. He refers to the river as a class three river, ‘where proprietors are allowed to make the rules.’ He said that anglers can keep the first salmon, but others must be thrown back. Some rivers allow all salmon to be kept whilst others require all salmon to be released. (In 2018, the river Dunbeath was classified as a Grade Three river which meant no fish could be killed).

Mark Kurlansky’s Salmon is an interesting book for the coffee table but as a seminal work on the life of salmon, it probably falls somewhat short. Anyone wanting to read this book will have to wait until May 14th for it to appear in book shops.