Is it a mystery?: The Press & Journal recently reported that the owner of Gordon Castle, a historic Speyside castle, has pledged to donate 10% of the sale of luxury products from its shop to help solve the mystery of why numbers of wild salmon in Scottish rivers have declined. Angus Gordon Lennox, the owner, said that the Atlantic Salmon Trust’s Missing Salmon Project is vital to help save this iconic fish.

By coincidence this week, ‘iNews’ reported that according to the AST, less than 5% of salmon that leave Britain’s waters now return. There is now concern that Atlantic salmon may become extinct. The AST say that if they do, then ‘we have only ourselves to blame. We have to stop killing them by inaction’.

The AST hopes to solve the mystery of where the salmon are dying through the Missing Salmon Project in which they track the young salmon down the rivers and out to sea.

The question is whether it is such a mystery why salmon stocks have declined so much. We don’t think the answer can be found in Scottish rivers now. Instead, we need to look back over many years. Since 1952, and probably well before too, anglers have been catching and killing an average of 88,500 wild fish from Scottish rivers every year. Of course, anglers are not solely to blame as commercial nets have also been responsible for large scale depletion of numbers too especially in the golden days.

We know from marine fish stocks that excessive harvesting leads to stock collapse so why would wild salmon be any different? In fact, wild salmon are more likely to collapse, because the fish targeted are breeding adults and removing these from the stock will reduce its capacity to reproduce.

Over the years human interference has added to salmon’s woes, with water abstraction and the placement of barriers, but regardless, the slaughter has continued, only slowing down in recent years. Catch and release want even recorded until 1994 and it is only in the last few years that it has reached levels that might have had an impact – although catch and release is not a real solution because it is possible that handling fish in this way reduces the viability and success of reproduction.

Now that anglers do return so many fish, there is a refusal to accept that the damage was done long ago. Anglers now say that their impact is minimal and thus the problems must be due to something else, hence the need to look for others to blame such as fish-eating birds and seals and not forgetting climate change.

The Missing Salmon Project is looking for reasons for the decline of wild salmon in east coast rivers but the real reason for the collapse is as everyone thinks they know is down to salmon farms. It is now being promoted that east coast fish pick up lice from Shetland or Norwegian farms during their migration north although it has never seemed to be a problem before now.

West coast salmon farms are the real culprits, and this is a constant theme from anglers and eco-critics. The problem is that anglers never hear the alternative view and thus it must be true. This week was a case in point. Former TV presenter and now Talk Radio host, Matthew Wright held a discussion about the evils of salmon farming. Mr Wright is a confirmed angler and is now vice -president of the Wild Trout Trust. He invited salmon farm critic Don Staniford on to his programme and they both attacked the salmon farming industry. There was no-one from the salmon farming industry on the programme to redress the balance, so the audience were left with a very negative view of the salmon farming industry. The angling media provide an equally one-sided view of salmon farming to their fishing audience. Is it not surprising that they are convinced that salmon farmers are to blame?

There was one part of the discussion between Mr Staniford and Mr Wright that caught our attention. The conversation jumped about a bit and we have ignored Mr Staniford’s usually over expressive comments, so we have paraphrased what was said:

Matthew Wright: I ask you this, aware of crashing populations of both Atlantic and Pacific salmon, can you ever envisage a time that if we got rid of fish farms a natural balance was restored and wild salmon populations started to climb and became a sustainable food again?

Don Staniford: Yes, we just need to move the salmon cages out of the lochs. We only started to put them in the lochs during the 1970s and 1980s and we know from evidence in Ireland that if you take the salmon cages out, wild fish bounce back. It may take two to three years, but they will bounce back.

Those who regularly follow Mr Staniford’s views will know that it is only in the last year that he has become more vocal about wild salmon in Scotland. We suspect that he is now funded by the wild fish lobby to make as much trouble as he can. We may be wrong, but Mr Staniford is as transparent as mud about his own administration, so there is no way of finding out.

His view that wild fish will bounce back once salmon farms are removed appears to be more unproven spin that fact. We don’t know what he refers to when he mentions what happened in Ireland on which he bases his view. What we do know is that a headline in the Irish Examiner this week stated: ‘Is the Irish salmon doomed to a watery grave?’ The report points out that the number of returning adult salmon to Irish rivers has dropped from 2 million in the 1970s to 250,000 now. Catches are at an all-time low and extinction in our lifetime is a possibility. Only 27 of Ireland’s 144 salmon rivers are currently not considered to be at risk. So, whatever happened in Ireland to cause Mr Staniford to suggest that stocks will bounce back, has clearly made no difference to the state of Irish wild salmon stocks.

It is all well and good spending millions of pounds on research but until there is open and free discussion about all the issues facing wild salmon, their survival will always be in doubt. We cannot understand why those interested in the future of wild salmon are so unwilling to sit down and discuss what is happening to wild salmon now. To us, this is a bigger mystery than why fish are failing to return to Scottish rivers. Back in 1993, a one-day conference was held in Inverness to discuss the plight of wild fish on the west coast. We don’t see why a series of similar meetings should not take place now. Maybe discussing ways to save wild salmon is not such a priority or maybe the fact that the most obvious immediate action, which is to stop fishing for wild salmon, is not acceptable to the wild salmon sector.

Dour Gour: A couple of the vocal minority of anti-salmon farm critics have been tweeting each other about the state of salmon stocks in some of the smaller rivers south of Fort William. They state ‘The Kingarloch, the Cona, Scaddle and Gour have no viable populations of salmonids left in them. This is a disgrace to any civilised society and its on your watch.’ The tweet is addressed to the Scottish ministers and the SSPO.

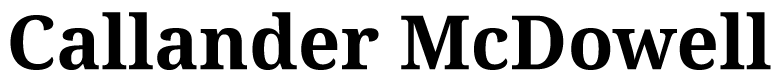

These rivers are located in the Scaddle and Gour fishery districts and because they are such small rivers, they rarely attract any attention. However, as we, at Callander McDowell. have plotted the salmon catch from every fishery district in Scotland, we can show the rod catch for both the Scaddle and the Gour. Rod catch is used by the Scottish Government as an indication of the stock.

The catch from the Scaddle has been somewhat intermittent over the years. The overall trend has been upwards. The gaps, especially during the 1990s are likely to be due to no fishing effort brought about by the claims from angling organisations that there were no fish left in west coast rivers due to the presence of salmon farms. Once anglers realised that this was untrue, and there were some good fish to be caught, fishing resumed, and catches have shown a subsequent increase.

The Gour is a very different story. No fishing has been recorded from this river since 1952 so there is no indication of the state of the stock. How these critics know that there are no fish left in the river is just another example of unjustified criticism of the salmon farming industry.

Earn a catch: We, at Callander McDowell, have regularly been told that only anglers understand wild salmon (and that our views are unwelcome). We were therefore interested in a report in the Courier newspaper about the regrading of the River Earn. Last year, the paper reported that after a major campaign by the anglers from the local fishing club, the Scottish Government reversed a decision to regrade the River Earn as a category 3 river. Scottish Government scientists changed the scientific model used to determine the size of the stock and as a result, the river was upgraded to a category 2 meaning that anglers could take a fish home for the pot.

The Courier has now reported that the after a year of poor catches, the river has been downgraded to a category 3 as previously determined. The newspaper says that one angler even wrote to the Scottish Government to complain about the fishing this season although we are unsure what he expects the Scottish Government to do more than what they have already done which is to ban the killing of fish on the river this coming year.

The local fisheries scientist, Dr David Summers from the Tay Salmon Fisheries board told the Courier that the categorisation of the river has nothing to do with the poor catches which are more part of a wider pattern affecting Scottish east coast rivers and if the situation continues then the river will be permanently classed a category 3 river.

We have always held the view that anglers can do what they want as long as they don’t blame others such as salmon farms when things go wrong but surely if there is such concern over the state of stocks then the only logical solution is to classify all Scottish rivers as grade 3 for the next five years and then reconsider because clearly salmon are already on the road to extinction and sooner or later anglers must accept that they are part of the problem.

In the pink: Following our comments in the last issue of reLAKSation about life being cruel and that whilst there is no excuse for mistreatment of any animal, we were sent a link to a video by one of our readers. We would first mention that in sharing this, we are not trying to highlight practices from any particular part of the world or by any specific workers etc. It is simply a video that we found of interest in relation to the issues we discussed. Given the other recent news about pink coloured water and scum emanating from one particular event, we were interested to see a similar occurrence here.

We suggest watching from about 18 minutes in.

Friendly fish: We were interested to see that among the ongoing protests by Extinction Rebellion in London, a group of animal rights activists calling themselves Animal Rebellion targeted Billingsgate Market last Saturday morning. They blocked the entrance to Billingsgate even though Saturday is not a main trading day as it is open to the public. According to the Guardian, one demonstrator locked herself to the gates. In all about 200 people gathered at around 3.30 am.

Kerri Waters, a spokesperson for Animal Rebellion told the paper that: To many, eating fish is seen as the healthy choice, but just as land animals suffer, so do fish. They can think, They can make friends and they can feel pain. Their suffering goes unnoticed.

She continued: ‘At London’s Billingsgate market, thousands of fish, stolen daily from their ocean homes, lie dead or dying. Many will have suffocated slowly when pulled on board fishing vessels whilst thousands of others remain alive as they’re transported by lorry to the market where they’ll be gutted or boiled alive’.

As we suggested previously, life is cruel, but fish get eaten by other animals besides us. It may be unappealing that us humans do kill in large numbers, but it is a proxy for the large number of humans on this planet. We make no apologies for highlighting that the real issue here is not about whether fish feel pain etc but whether our own population is simply out of control and rather than arguing that we are damaging the planet, maybe we should be asking whether our population growth is really at the heart of the matter. Instead of getting friendly with each other perhaps we should become more friendly with a fish.