‘It’s as plain as the nose of your face’ by Dr Martin Jaffa

In 1998, the July 4th issue of New Scientist magazine reported that the ‘catastrophic decline of wild sea trout in northwest Scotland is largely due to commercial salmon farming’. Government scientists who advise the Scottish Office, ‘have concluded that lice from farmed salmon are a “major contributory factor” in the collapse’. One senior government scientist, who wished to remain anonymous, told New Scientist that ‘It’s as plain as the nose of your face’.

Given the expression of such an unequivocal message, it is not surprising that the salmon farming industry has had a battle on its hands to prove its innocence, not that much of a battle has been evident. It sometimes feels more like a lone voice.

In particular, the focus of this battle has been the collapse of the Loch Maree sea trout fishery, which occurred in the late 1980s seemingly after a salmon farm was established in the adjacent Loch Ewe. The main antagonists have been the angler’s representative organisation, the Salmon & Trout Association (now known as Salmon & Trout Conservation) who have been campaigning to have the farm removed from Loch Ewe. They say that this is the only way that sea trout stocks in Loch Maree will ever recover.

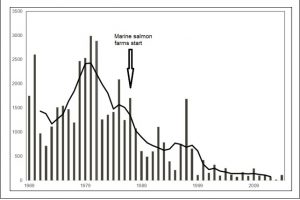

The collapse of the Loch Maree sea trout fishery needs to be first put into context. Sea trout numbers caught by anglers have been recorded by the Scottish Government since 1952. What is clear is that the number of sea trout caught in the north-west Highlands has been in decline since then. In fact, sea trout catches have been in decline across all of Scotland and not just the areas where salmon are farmed. Catches from Loch Maree also declined form 1952 onwards but during the 1970s, they rapidly improved. Loch Maree appeared to be bucking the trend. For example, nearby Loch Stack, another famous sea trout fishery, collapsed before the advent of salmon farming but this collapse is rarely discussed. The improvement in Loch Maree catches may have been because of increased policing of illegal netting in Loch Ewe that happened at that time. This allowed more sea trout to swim up the River Ewe to Loch Maree for anglers to catch. Whatever the reason, catches peaked in 1980 and as the five-year average graph by Butler and Walker (2006) highlights, catches then began to collapse.

It was this graph, with its reference to the establishment of the farm in Loch Ewe that originally caught my attention. Clearly, catches were in decline prior to the arrival of the salmon farm. In addition, Butler and Walker appeared to ignore the earlier declines from 1952 onward as did Dr Walker when he was commissioned by Salmon & Trout Conservation (S&TC) to write a new report criticising the salmon farming industry in 2016. Andrew Graham Stewart of S&TC has said that there is no other plausible explanation for the collapse of the Loch Maree sea trout fishery than the presence of the salmon farm in Loch Ewe.

In January this year, I was sent a copy of a report published by the Scottish Creel Fishermen’s Federation (SCFF). This organisation is campaigning for the return of the three-mile fishing limit around Scotland’s coast. The three -mile limit had been in place since 1889 to help protect in-shore fisheries from the impact of newly developed steam powered trawling. This new technology had brought about a rapid depletion of fish stocks closer to shore. However, following the Cod Wars with Iceland during the 1970s, Scottish fishermen campaigned to open local waters to fishing, as the loss of access to Icelandic fishing grounds had a significant impact on their incomes. The UK Government acceded to their demands and in 1984, they implemented the Inshore Fishing (Scotland) Act which removed the protection of the three-mile limit. This allowed trawlers to fish close to shore which meant on the west coast, that boast could trawl right into the many sea lochs including Loch Ewe. Given that the three-mile limit was introduced in response to stock depletion by industrial trawling, it was possibly predictable what would happen next.

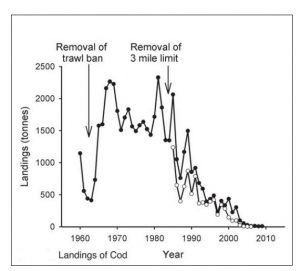

The SCFF report included reference to a scientific paper co-authored by world-renowned fisheries scientist Professor Callum Roberts of York University. The paper considered changes that have affected marine fish landings from the Inner Clyde fishing grounds over the last hundred years. The report included a graph of cod landings taken from Professor Roberts paper. Seeing this graph was something of a Eureka moment.

What was so overwhelming apparent was the sudden collapse of cod landings after the removal of the three-mile limit in 1984. Between then and 2009, landings of cod fell by 99%. This graph might have been for fish caught from the Inner Clyde fishing ground, but the similarity with the decline of sea trout catches from Loch Maree was astonishing.

The parallels between the collapse of cod landings and sea trout catches after 1984 clearly merited further investigation. However, a couple of issues immediately became apparent. Firstly, landings of marine fish are not necessarily an accurate reflection of the stock. It is possible that there may be plenty of fish swimming about but that they are not being landed at the local ports. Secondly, the collapse of landings might suggest that fishing effort has also declined in which case, if trawlers had anything to do with the collapse of the Loch Maree fishery, why had sea trout catches not subsequently recovered now that there is no longer fishing for these demersal species?

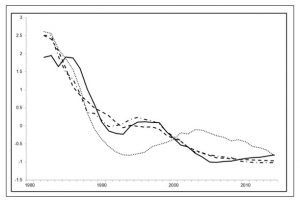

Scottish Government scientists have been collecting rod catch data for sea trout since 1952. These scientists have also compiled sea fisheries statistics, but for much longer. Data for all commercial species landed at all Scottish ports is therefore readily available and is published as an annual report. From this, I extracted landings data for three main species; cod, whiting and saithe for all west coast ports. However, I excluded data from the port of Kinlochbervie because the port is used by many boats sailing out of east coast ports for dropping off catch on their way home in order to get the best price for freshest fish. A lot of fish landed at Kinlochbervie is unlikely to have been caught from nearby in-shore waters.

The data for these three species and for sea trout (weights) were collated as five-year moving averages and then standardised to fit the same scale. The resulting graph is just as astonishing as the Callum Roberts’ graph of the cod collapse.

Landings of cod (dashed line) whiting (dashed and dotted) and Loch Maree sea trout (solid line) appear closely correlated. Whilst correlation does not imply causation, the rate of decline are extremely close. Landings of saithe (dotted line) vary most but show a similar trajectory. Whilst Andrew Graham Stewart claims that there is no other plausible explanation for the collapse of the Loch Maree sea trout fishery other than salmon farming, there does seem an extremely compelling case to suggest that the removal of the three-mile limit is a major factor in the decline.

This raises an obvious question that had Salmon & Trout Conservation been not so focussed on blaming the salmon farming industry, they might have come across this relationship before now and possibly campaigned for the reintroduction of the three-mile limit as a way of conserving sea trout stocks a long time ago. At the same time, it is surprising that the Government scientists at Marine Scotland Science hadn’t realised that there may be a connection between declining sea trout stocks and the removal of the three-mile limit especially as they collect and collate both sets of data. It’s possible that they never even considered looking for this relationship after their now retired fisheries scientist, Andy Walker published his paper with James Butler in 2006 that implied sea trout catches from Loch Maree were the result of local salmon farming activity.

Another question raised was whether the impact of removing the three-mile limit had any impact on wild fish catches elsewhere in Scotland. Cumulatively, sea trout catches from east coast rivers have also been in decline since the 1950s. However, because of the wide range of different river types, the trends for each river has varied significantly. For example, sea trout catches from the River Deveron did decline after 1984 as do demersal fish landings at McDuff, the fishing port located at the mouth of the River Deveron. Whether the two declines are connected requires further investigation.

The north coast of Scotland is more interesting still. This is because of Loch Eriboll and its associated rivers; the Hope and the Polla. Unlike in other parts of Scotland, these two rivers, the Hope especially, appear to be doing quite well in terms of sea trout catches. This is despite there being two salmon farms in Loch Eriboll. The River Hope emerges into the loch almost at its mouth and Andrew Graham Stewart has argued that the fish migrate out of the river and swim straight out to sea therefore avoiding any contact with the sea lice that might be present due to the farms. Of course, the reason that sea trout stocks are holding their own in this area could be due the fact that trawlers have never fished in Loch Eriboll. The reason is unclear, but it has been suggested that unlike west coast lochs which has a relatively smooth bottom, Loch Eriboll is extremely rocky and unsuitable for trawling. Could it be the absence of trawling has allowed sea trout stocks to flourish since 1984? Again, further investigation is required.

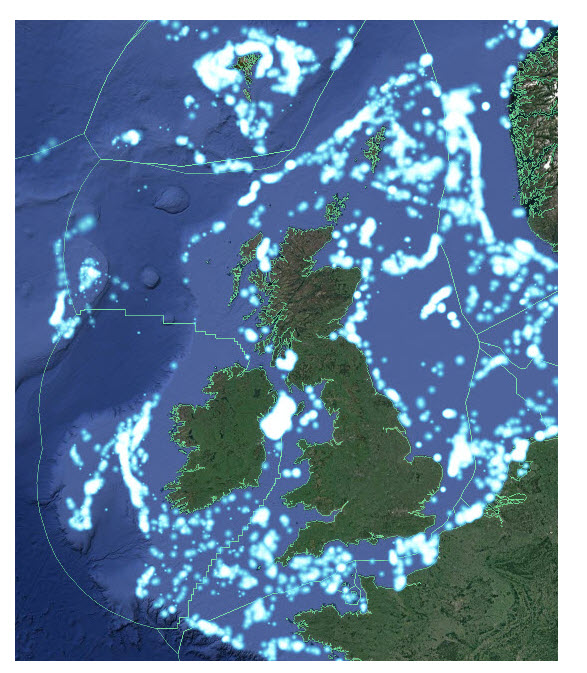

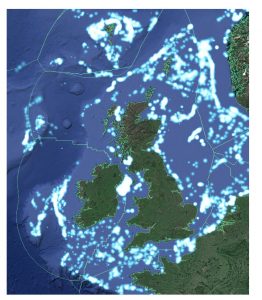

Finally, the graph of declining cod landings appears to show that by around the year 2000, the tonnage landed was negligible. This might suggest that trawlers no longer fish for cod and other white fish species around the coast because stocks have vanished. With no fishing activity for marine fish, stocks of sea trout might have expected to have recovered. However, the decline of stocks of demersal fish provided a space, which prawns have now filled. As a result, whilst landings of white fish species have almost disappeared, landings of prawns have skyrocketed. Thus, there is still significant fishing activity in in-shore waters, especially north of Skye. This can be seen from the screenshot from the Global Fishing Watch website who monitor fishing boats. The large white visible blob are likely to be prawn boats.

The Scottish prawn industry has regularly featured on TV programmes, so that there is a lot more awareness of what they do. What has been especially illuminating is the amount of other species caught in their hauls. However, a much lesser known fact is that in 2012 the Scottish prawn fishery had been adjudged to be the fifth worst in the world for by-catch. An analysis of the catch from boats in the Inner Clyde fishing grounds suggests between 66 and 80% is discarded.

Together, all this evidence suggests that salmon farming may not be responsible for the collapse of the Loch Maree sea trout fishery. Certainly, the removal of the three-mile limit offers a much more plausible explanation for the collapse and that might be plainer than the nose on anyone’s face!

This commentary appeared first in Fish Farmer magazine – https://www.fishfarmermagazine.com/