Restorative: Anti-salmon farming campaigner Corin Smith signed off from Facebook over the Christmas period by asking if there was any hope for restoring wild fish stocks in the aquaculture zone? His answer was yes, and the evidence was presented to his followers as an early Christmas gift.

His explanation is that the River Ewe has been experiencing increased runs of wild salmon that break with the trend of declining runs around the country. The reason, Mr Smith suggests that the farm closest to the river has had its capacity reduced by 50% so for the first time, there is a case study where salmon farming has increased and decreased in one area, Mr Smith says that what is apparent is there is an inverse correlation between the average biomass of a salmon farm and the abundance of a run of wild salmon that migrate past the farm.

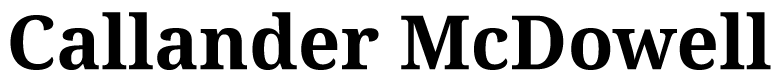

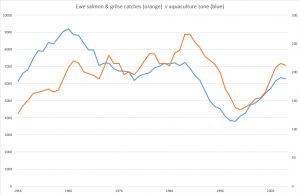

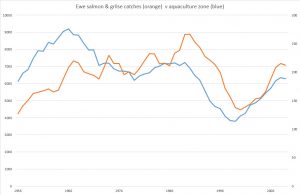

Mr Smith posted three graphs as evidence (https://www.facebook.com/InsideScottishSalmonFeedlots/photos/pcb.635565503526526/635564073526669/?type=3&theater), which we have redrawn to help examine his theory. The most important graph is the catch of salmon and grilse from the River Ewe from 1952. This also includes a line of the 10-year average, which illustrates his claims. From about 1996 to 2002, the 10-year average shows that salmon catches declined after many years of increases. The decline began about eight years after the salmon farm was established in Loch Ewe. According to the graph, catches even in 1996 were very good but dropped quite dramatically the following year. Around 2005, the 10-year average reached its lowest point and has increased ever since.

Mr Smith’s explanation is that the arrival of the salmon farm brought about a reduction in the number of salmon passing through Loch Ewe. Although he doesn’t say it specifically, the implication is that lice from the farm were harming the runs of wild fish. This is despite Mr Smith relating in an interview on the Pace Brothers podcast that migrating salmon do not linger in the loch and therefore hardly come into contact with the salmon farm.

He continues that in 2002, the salmon farm moved to a location further down the loch. This increased distance reduces the impact on the wild salmon runs and hence there has been an increase in catches. A recent reduction in biomass on the farm site has helped produce further improvements in the past few years (although our graph only runs to 2014, which was when we last analysed the data.)

There are a couple of problems with Mr Smith’s explanation of the impacts of the farms in Loch Ewe. Whilst the farm did move in 2002, it only moved a further 5km into the loch. Yet, Marine Scotland Science claim that salmon farms impact wild fish up to 31km away.

Secondly, had Mr Smith only posted the one graph of Loch Ewe salmon catches, he might have provided a plausible explanation for the change of fortune of Loch Ewe salmon catches. However, he also posted a graph of catches from the whole of the aquaculture zone including the 10-year average. Rather surprisingly, the graph follows a similar pattern to catches from Loch Ewe. To help compare Loch Ewe catches with those from the wider aquaculture zone, we have drawn both 10-year average lines on the same graph.

This clearly shows that catches from the aquaculture zone also began to decline around 1995/96 and then recovered around 2003. The one thing of which we can be certain is that the relocation of the farm in Loch Ewe has not influenced catches from as far away as the Hope in the north and the Ruel fishery district in the south. The change in catch numbers clearly happened for other reasons.

Whilst nothing can 100% certain, we do remember that from the early 1990s, there was a great deal of negative publicity about salmon farming arising from the events in Loch Maree. The general impression promoted at the time was that salmon farming was responsible for the extermination of wild fish stocks along Scotland’s west coast. As a consequence of this negative publicity, anglers avoided fishing the west coast rivers. Why would they pay huge sums to fish in rivers with no chance of catching anything? Inevitably, the catches of salmon and grilse slumped simply because of a significant reduction in fishing effort. Yet, within six or seven years, anglers began to realise that those who had ignored the warnings of no catches, were actually still landing good catches of even large salmon and hence anglers began to return to the west coast to fish for salmon. As we have reported, even one of the most vocal salmon farming critic, Andrew Graham Stewart of Salmon & Trout Conservation Scotland took a fishing holiday in 2018 on the River Ewe.

The reality is that salmon farming has hardly influenced salmon catches along the west coast. We know that fewer wild salmon have returned to all Scottish rivers since the 1980’s. This has had a much greater impact on the smaller west coast rivers than those of the east coast. Despite a much greater reservoir of fish in the east, even the larger east coast rivers are now experiencing the same impacts as the west coast. This has nothing to do with salmon farming.

Unfortunately, Mr Smith will have to return to the drawing board if he is to come up with a plan to restore west coast rivers to their former glory.

For further reading we suggest reading Loch Maree’s Missing Sea Trout by Dr Martin Jaffa available through Amazon https://www.amazon.co.uk/Loch-Marees-Missing-Sea-Trout/dp/199997140X/ref=sr_1_fkmr0_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1545822987&sr=8-1-fkmr0&keywords=loch+marrees+missing+sea+trout

Or now available through Coch-Y-Bonddu Books https://www.anglebooks.com/loch-maree-s-missing-sea-trout-are-salmon-farms-to-blame-by-martin-jaffa.html

Restoring Maree: Corin Smith’s Christmas present is not his first attempt to promote the restoration of angling on the Ewe System. Seemingly, he made a presentation to Salmon & Trout Conservation’s MSP guests during the reception at the Scottish Parliament launching their campaign to restore the Loch Maree sea trout fishery. Recently, Mr Smith uploaded his presentation to his Facebook pages enabling a wider audience to access his views.

We found Mr Smith’s presentation to be extremely interesting and given a broader forum, it might lead to a thought-provoking discussion. Mr Smith argues that if the Loch Maree sea trout fishery was restored it could create nearly 2,600 rod days of fishing, generating £1.4 million. Mr Smith also suggests that if fisheries along the whole west coast were also restored, nearly 100,000 rod days of fishing might result generating £87 million and creating 182 full-time equivalent jobs. Such restoration might lead to the construction of 5 world class fishing lodges, 15 Tier one lodges and 100 new self-catering properties.

This all sounds very exciting and so we are very reluctant to pour cold water on his plans. Mr Smith makes a very convincing case in terms of jobs and revenue, but his presentation lacks one small detail. He omits to mention how these fisheries will be restored. The only clue is that Mr Smith includes the graph showing the decline of Loch Maree sea trout catches linking to the arrival of salmon farming in Loch Ewe. The implication is that if salmon farming is moved, then the fish will return and so will the anglers.

If only it were so simple.

We at Callander McDowell are still waiting for anyone from the wild fish sector to explain the graph of sea trout catches in the aquaculture zone since 1952. Catches were in decline long before the arrival of salmon farming. Instead, Mr Smith and Salmon & Trout Conservation rely on their own graph to link salmon farming to the decline of sea trout, but this graph is extremely misleading and does not reflect the trends that have affected Loch Maree.

We appreciate that the wild fisheries sector dismisses anything we, or anyone from the aquaculture industry, says so we will end this commentary with a short extract from a paper given at a symposium in Oban in June 1987, a date which coincided with the arrival of salmon farming in Loch Ewe. The paper by M Picken states:

The River Ewe/Loch Maree catches show a steady decline from 1952 to the early 1960s, a peak in the later 1960s followed by a decline until about 1973. Then there was a steady increase throughout the 1970s followed after that by a decline to the general pre-1970s level.

For reference, M Picken’s comments about Loch Stack are also of interest:

Historically, the name of Loch Stack was a password for excellence in sea trout circles. Before 1952, it was fished by a few members of the proprietor’s family, however Young (1885) mentions that it was Scotland’s premier loch for sea trout in terms of numbers and size. Unfortunately, its reputation has been eroded by a steady decline in catches from 1960 to 1965 and again in the late 1970s.

The Future: BBC News have reported that the railway station located between Middlesbrough and Redcar in the north east of England has been named at Britain’s least used station. In 2017/18 only 40 people (or one person forty times) used Redcar British Steel station. The reason for the low number of passengers using the station is not hard to understand. The station served the former British Steel plant that closed in 2015. Teesside was once the home of one of the largest steel works in a Britain. In its heyday, Dorman Long, as it used to be known, built the world-famous Sydney Harbour Bridge. Now the site is a picture of desolation.

Steel production used to be one of Britain’s major industries. During the 1970s, over 320,000 people were employed in steel production. Today the number is less than 10% and most are employed in specialist production. World demand for steel has shrunk and many steelworks have simply been unable to compete.

Drax power station is the UK’s largest coal fired power station and is soon to complete a conversion to being fuelled by biomass. Demand for coal has been falling over many years and this has been reflected in the closure of the coal mining industry. In the 1970s, over 250,000 miners were employed whilst today they are numbered in the hundreds if that. Coal was no longer economic to mine and together with efforts to reduce carbon footprint, means that what was once one of the great British industries has almost disappeared.

During the 1960s, over 50,000 people were employed as fishermen. Today the figure is less than 12,000 of which at least 2,000 are part-time. The reasons for the decline are well-documented but simply put there were too many fishermen chasing too few fish. Even with reduced fishing pressure, environmental groups continue to warn that fish stocks remain under threat.

Of course, it is not just stocks of cod and haddock that are under threat. Atlantic salmon and sea trout numbers are also in peril. The writing has been on the wall for many years, but little has been done to address the problems. Instead, the wild fish sector has simply looked for someone to blame. If it’s not the salmon farming industry, it’s the nets, or hydro-electric, fish eating birds, seals or even canoeists or rafters. In our opinion, the decline has occurred for much more fundamental reasons and first became apparent in the short spate rivers of the west coast but now has spread to the east where the larger rivers have previously afforded greater protection to the more sizeable stocks of fish.

The fact that even the big four rivers of the east coast are now suffering significant declines in the number of fish caught shows that action must be taken if the wild fish sector is to avoid a similar fate to the steel, coal and fishing industries.

2019 is the ’International Year of the Salmon’ so perhaps this designation might help focus attention on the plight of salmon across all its range. The Norwegian organisation, Sjømat Norge (Seafood Norway), have said that the ‘Year of the Salmon’ does not mean the ‘Year of the Salmon Fisherman’. The year is about what is good for the salmon, not about what is good for salmon anglers. Geir Ove Ystmark, Managing Director of Seafood Norway told Intrafish that when the cod stock collapsed in the mid-1980s and the herring stocks collapsed in the 1960s, commercial fishermen had to adapt and therefore if salmon fishermen now need to adapt, then that is what must happen.

We, at Callander McDowell, certainly agree.

We know, that as usual, there will be howls of protest from the wild fish sector in Scotland with claims that only the anglers know what’s best for wild salmon and sea trout and that those with a background in salmon aquaculture have no right to comment. Yet sometimes it takes people from outside the sector to see what is blindingly obvious.

Even though wild fish stocks have been in decline for years, it is only relatively recently that the wild fish sector has swung into action. Their main approach is to try to put together a list of likely suspects, whilst at the same investing over £1 million into the Missing Salmon Project. The Atlantic Salmon Trust have just published a new booklet about their project https://gallery.mailchimp.com/20c4bafc08bf0f77b36982fc1/files/11efa46c-25b7-435a-9913-aeedda0fd97e/MSP_DEC_18_SP.pdf. The aim to track salmon from the upper reaches of the freshwater catchments out into the sea with the aim of identifying where losses of fish occur during their long journey. The new booklet lists examples of the mortality suspects at various points in salmon’s migration route. For example, commercial forestry and agricultural runoff could affect the headwaters, avian predation in the main body of the river, seals in estuarine, aquaculture and netting in the coastal zone, whilst the open ocean could impact with pelagic by-catch and climate change. Interestingly, there is no mention of angling as potentially impacting on salmon stocks.

2018 was a difficult year for salmon angling as high temperatures meant many fish entry into the river systems was delayed due to low water levels. It is unclear whether this was an exceptional year or now part of the norm. Thus, it is impossible to know whether any results of tracking are typical of what is happening in the rivers or the consequence of unusual climatic conditions. Repeating the tracking over a number of years is the only way to guarantee a clear picture. However, we, at Callander McDowell actually think that trying to understand what is happening to the fish is a luxury the wild fish sector cannot afford. It is action, not knowledge that is now required.

Knowing, for example, if fish-eating birds prove to be the problem will be of little help. The birds might lead to fewer fish returning to the rivers to breed, but the AST are never going to obtain approval for a realistic solution. Anglers may well want to shoot as many of these birds as possible, but of course the environmental sector will never ever allow widespread culling of fish-eating birds. Equally, if seals are shown to be the problem, permission for the widespread shooting of seals will never be granted and there is little the wild fish sector can do about it.

The reality is that remedial action is not the solution. Instead, a more positive approach is required. The wild fish sector can continue to bleat and moan and blame everyone else but themselves for the lack of fish. Eventually, the lack of returning fish will mean that salmon fishing is no longer viable in Scotland because the size of the stock no longer merits any form of exploitation. Salmon angling can suffer the same fate as the steel and coal industries to be consigned to history.

The alternative is to try to boost stocks leaving the rivers in the hope that more fish will return and help ensure angling continues to contribute to local economies. The problem is that the wild fish sector is rather ambivalent to the idea of hatchery raised fish. In 2013, the Rivers and Fisheries Trust for Scotland reviewed the strategy for restocking and concluded that more damage than good can result from using restocking rivers with hatchery raised fish. Despite this, hatcheries are in use on a number of major rivers although typically, the fertilised eggs they produce are stocked out before the fish hatch. RAFTS believed that the benefit of this approach was actually minimal.

There are other approaches to restocking such as raising the fish through to smolt, which are then released. These have the benefit of not competing with the fish developing naturally in the river. Certainly, this approach has been a great success in Alaska where the release of ranched smolts have produced bumper runs of returning salmon which are then exploited by commercial fishermen.

A similar approach has been adopted on the west coast River Carron, although various life stages are stocked. In the period from 1952 to 2003 catches from the Carron average 57 salmon and 23 grilse. This includes a time when salmon stocks across Scotland have been very high and also the time before the onset of salmon farming. A restocking programme was instigated in 2003 and from then until present, the average catch has been 92 salmon and 131 grilse. During this period, salmon cages have been present in Loch Carron and Loch Kishorn.

The River Carron River Manager, Bob Kindness has said that the only plausible explanation for the increase has been stocking to ensure a very healthy smolt output. The numbers of smolts are monitored using a rotary screw trap rather than the guestimate used on many other rivers.

Iceland is also known for its successful programme of restocking of smolts. Despite such success, there are still major objections to restocking with concerns about the genetic integrity of the fish; questions as to whether the fish have been domesticated etc but all these concerns mask just one key objection and that is the cost. Many of those involved in the wild fish do not see why they should pay for something that should happen naturally.

The problem is that it is not happening naturally.

The River Ness District Salmon Fishery Board conducted a paper exercise to calculate the cost of a restocking programme with smolts. They estimated that it would cost about £1 a smolt and in order to boost catches from current levels (2014) to bring catches back to those of the 1950s would require the production of nearly 680,000 smolts, equating to £680,000. They say that their annual budget is about £100,000 so the cost of such a programme would be outside their capability.

Yet, the River Ness DSFB has a bigger budget than the tiny west coast River Carron and the people there have managed to boost catches. Meanwhile, catches from east coast rivers continue to decline.

Another river with good catches this year is the Yorkshire River Ure. The River Ure Trust have been raising young fish in what they describe as semi-natural rearing ponds, which they say produces a fitter, tougher and better adapted smolt, without placing the natural population at risk. It is also a less costly way to produce smolts. Improved catches suggest they are having a positive impact on what was once a near dead river.

The wild fish sector has a choice, it can either invest in stocking or else watch salmon angling slip into a decline that will lead to a complete ban on fishing. The writing is on the wall with the closure of commercial netting. How long will it be before angling fisheries are closed too?